Pressing for Yet More

John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

President, Hussman Investment Trust

January 2025

That the free-enterprise economy is given to recurrent episodes of speculation will be agreed. There is protection only in a clear perception of the characteristics common to these flights… There are, however, few matters on which such a warning is less welcomed. Those involved with the speculation are experiencing an increase in wealth – getting rich or being further enriched. No one wishes to believe that this is fortuitous or undeserved; all wish to think that it is the result of their own superior insight or intuition. Speculation buys up, in a very practical way, the intelligence of those involved. As long as they are in, they have a strong pecuniary commitment to belief in the unique personal intelligence that tells them that there will be yet more.”

– John Kenneth Galbraith, A Short History of Financial Euphoria

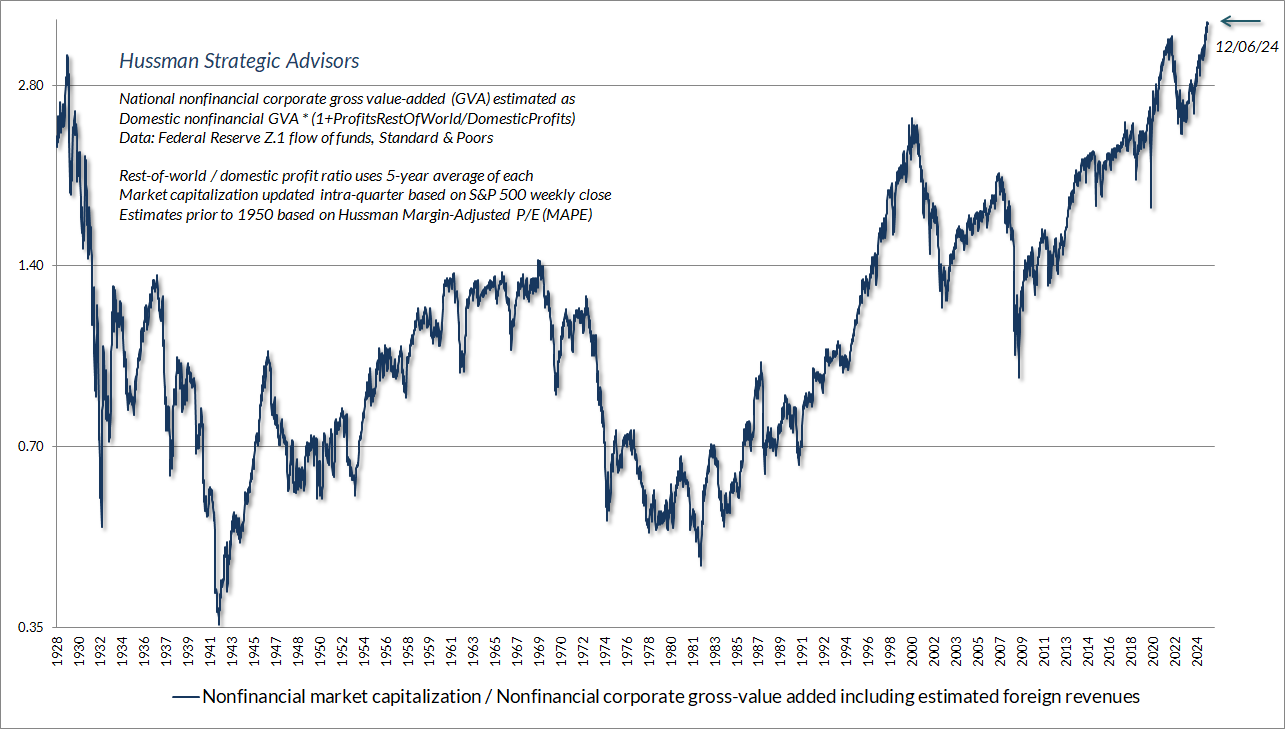

On December 6, the S&P 500 set the most extreme level of valuations on record, exceeding both the 1929 and 2000 market peaks on measures that we find best-correlated with actual, subsequent 10-12 year S&P 500 total returns across a century of market cycles.

Reliable valuation measures are enormously informative about both long-term investment returns and the potential depth of market losses over the completion of any given market cycle. At the same time, valuations are of strikingly little use in projecting market outcomes over shorter segments of the market cycle. Investor psychology – the desire to speculate, or the aversion to risk – has a much stronger impact, which is why we also have to attend to factors including market internals, sentiment, short-term overextension / compression, and monetary policy (while unfavorable market internals dominate monetary easing, favorable internals amplify it).

Amid the untethered enthusiasm about artificial intelligence, and prospects for deregulation and lower corporate taxes, it’s worth repeating that despite all the society-changing innovations of the past 20-30 years, both GDP and S&P 500 Index revenues (which include the impact of stock buybacks) have grown at an average rate of only about 4.5% annually. That’s slower, not faster, than the growth rate during the preceding half-century.

Yes, the largest companies are very profitable, but that’s nearly always true at speculative extremes. That cohort of mega-cap companies is constantly changing, and except on their approach to extremes like 1929, 1972, 2000, and today, the companies with the largest market capitalizations have historically gone on to lag the S&P 500 over time.

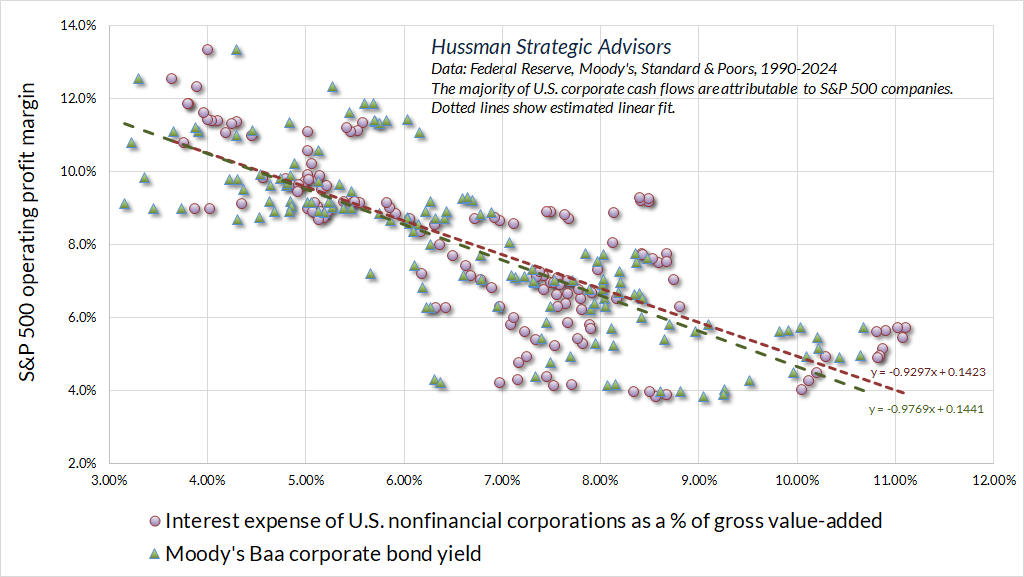

Investors regularly forget that the central feature of free-enterprise is the continual emergence of innovation-driven “new eras” in which both profit margins and growth rates are trajectories rather than durable numbers. As I reviewed in last month’s comment, Ring Out Wild Bells, the primary driver of rising profit margins since 1990 has not been rapid productivity growth or higher EBIT margins (earnings before interest and taxes). The simple reality is that most of the expansion in profit margins since 1990 is explained by falling interest expense, thanks to persistently declining interest rates that companies temporarily locked in at the 2020-2021 lows.

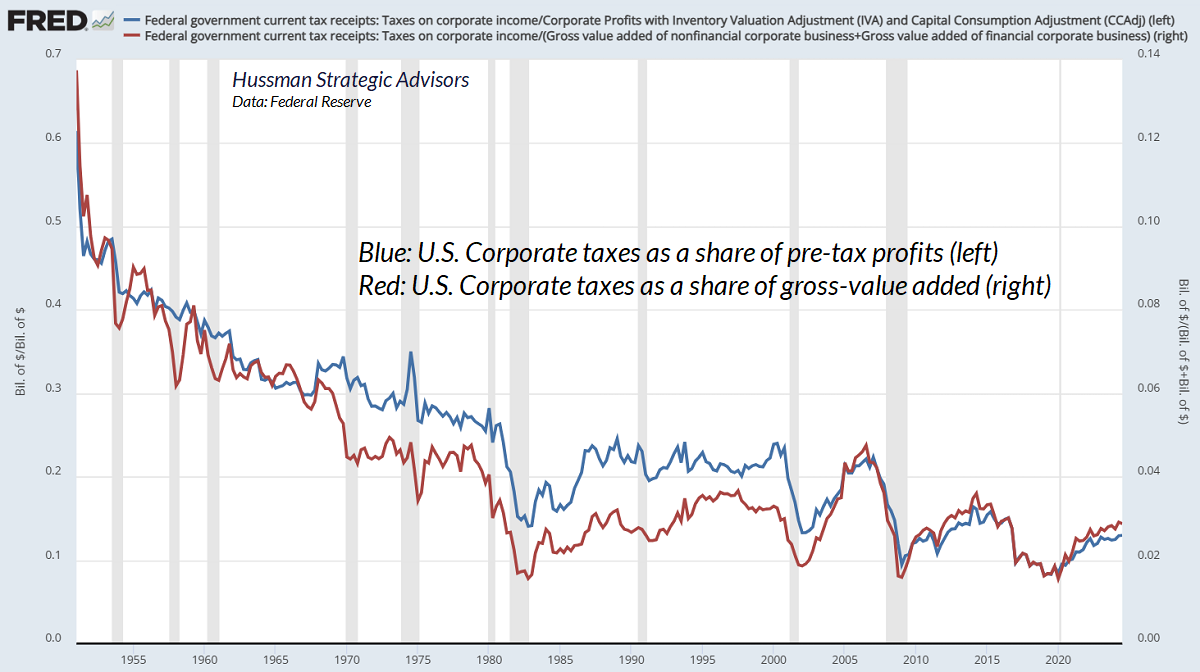

Meanwhile, most of the historical impact of corporate tax reductions was reflected in profit margins by the early 1980’s. Even if corporate taxes were reduced by one-third from here, and assuming those tax cuts were sustained permanently, the value of that tax reduction would amount to just 4% of market capitalization, and after-tax profit margins would increase by less than 1%.

Having priced the stock market at elevated multiples of record earnings, investors now require profit margins to sustain record highs permanently – simply for growth in earnings and payouts to match the 4.5% revenue growth rate of recent decades, and they require the S&P 500 price/revenue ratio to remain at a permanently high plateau, three times its historical norm.

Given our own 4-year baseline expectation for real GDP growth of just 1.5% (see The Turtle and the Pendulum), even 4.5% nominal growth would require either a 3% inflation rate in the coming years, or a 2% inflation rate coupled with a jump in productivity that fully restores the 1948-2000 average.

One might hope for higher inflation, imagining that it might produce higher nominal growth and accompanying market returns, but that would require valuations to remain at record extremes. Unfortunately, valuations are the first casualty of persistent inflation. In fact, except when valuations have been at least 25% below historical norms, the S&P 500 has lagged Treasury bills, on average, when consumer price inflation has been anything over 4%.

There’s no question that investors are eager to justify record valuation multiples by appealing to the growing share of technology companies in the S&P 500. Yet the technology sector itself is trading at the highest multiple to revenues on record. Meanwhile, the growth rate of overall S&P 500 revenues, which include the technology sector, is below historical norms while the S&P 500 price/revenue multiple is three times its historical norm, easily eclipsing the 1929 and 2000 peaks.

Still, for the moment, neither valuations nor arithmetic matter to investors. As Galbraith observed, “As long as they are in, they have a strong pecuniary commitment to belief in the unique personal intelligence that tells them that there will be yet more.”

Hence the sort of magazine cover Barron’s ran only a week after the S&P 500 set its recent record high – “Embrace the bubble.”

What defines a bubble is that investors drive valuations higher without simultaneously adjusting expectations for returns lower. That is, investors extrapolate past returns based on price behavior, even though those expectations are inconsistent with the returns that would equate price with discounted cash flows. The defining feature of a bubble is inconsistency between expected returns based on price behavior and expected returns based on valuations.

John P. Hussman, Ph.D., How to Spot a Bubble, March 2021

A review and update of market conditions

Our most reliable gauges of market valuation continue to trace out what I view as the extended peak of the third great speculative bubble in U.S. history – implying the most negative prospects for expected S&P 500 total returns on record. Still, valuations are not a timing tool. Given the continued unfavorable (and deteriorating) status of our key gauge of market internals, along with a continued preponderance of overextended warning syndromes, our investment outlook remains clearly negative.

Although there are many points in history when the S&P 500 advanced despite a combination of elevated valuations and unfavorable internals, including the approaches to the 1972, 2000 and 2007 market peaks, there’s no question that an additional speculative tailwind was added in 2024 by Wall Street’s exuberance about AI and its eagerness for profit-centric policy shifts. As I noted in the September Asking a Better Question, given the internal divergences we observe (which have worsened considerably in recent weeks), my impression is that our gauge of internals remains unfavorable precisely because of the internal divergences it is designed to measure. It’s the wrong question to ask how we might cleverly dart between a defensive outlook and a bullish one amid historically ominous market conditions. The better question was how to vary the intensity of a valid defensive outlook, in a way that can be expected to benefit even in a further advance, provided only that the market fluctuates along the way.

At present, based on the hedging adaptation we implemented in late-September, we aren’t inclined to tighten our put option hedges further the event of a continued market advance. Our outlook is clearly bearish here, but it’s not one I expect to amplify at the moment. As I detailed in Subsets and Sensibility, one of the features of this hedging adaptation is that it reduces our risk of “fighting” market advances even in market conditions that are quite hostile from a historical perspective.

With respect to prevailing conditions, the chart below reviews our most reliable gauge of market valuations in data since 1928: the ratio of nonfinancial market capitalization to gross value-added (MarketCap/GVA). Gross value-added is the sum of corporate revenues generated incrementally at each stage of production, so MarketCap/GVA might be reasonably be viewed as an economy-wide, apples-to-apples price/revenue multiple for U.S. nonfinancial corporations.

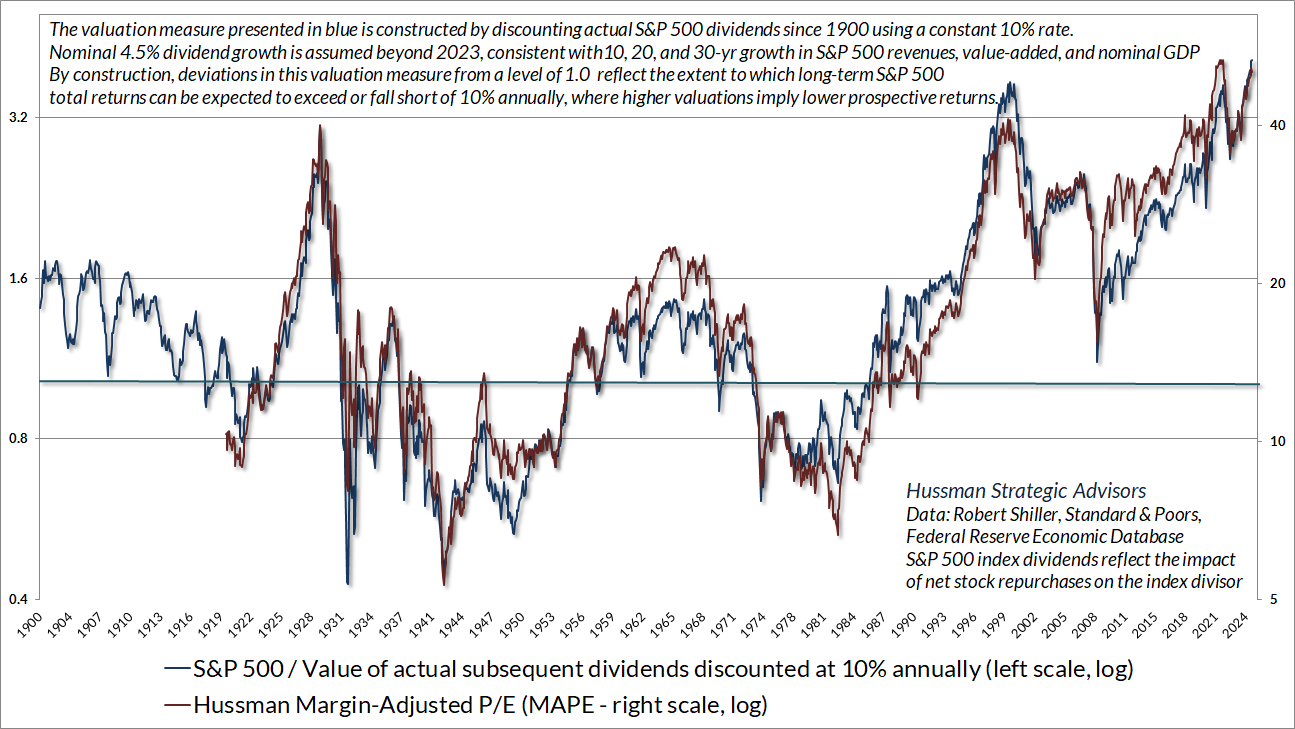

The chart below shows our Margin-Adjusted P/E, which considers cyclical variations in profit margins and their impact on the price/earnings ratio, along with the ratio of the S&P 500 to the present value of actual subsequent S&P 500 dividends at every point in time since 1900, discounted at a constant rate of 10% annually (see chart text for additional details). The ratio therefore estimates the extent to which likely long-term S&P 500 total returns are likely to depart from a 10% average return. The higher the valuation, the larger the expected shortfall from historically run-of-the-mill expected returns of 10%.

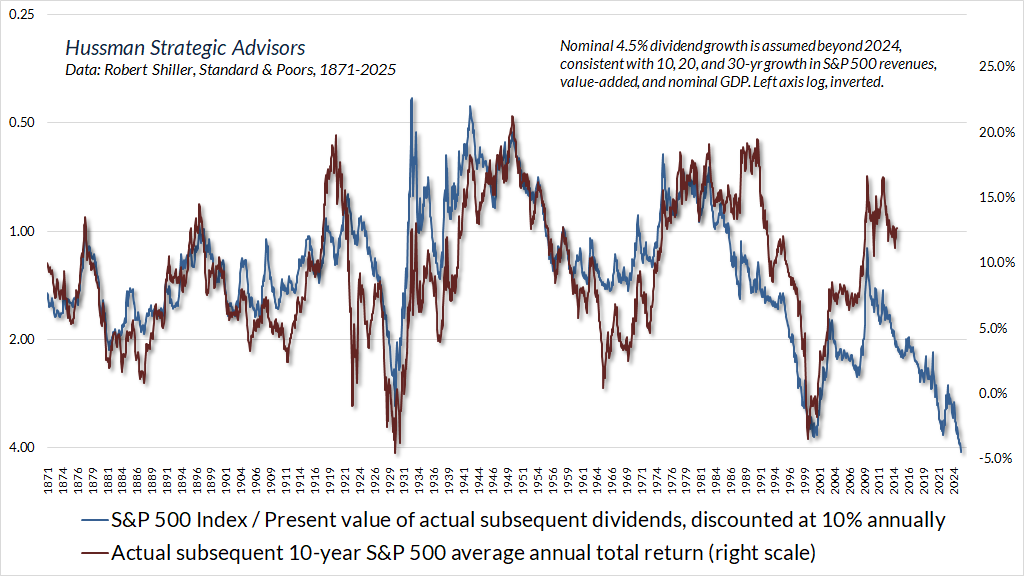

The chart below shows how our S&P 500 dividend discount model above is related to actual subsequent S&P 500 total returns in data since 1871. The relationship clearly isn’t perfect. As with every good valuation measure, the “errors” typically reflect extreme valuations at the endpoint of a given investment horizon. For example, actual 10-year market returns (red) were substantially higher than expected returns (blue) in the 10-year period beginning in 1919. The reason is that the endpoint of that 10-year horizon was the 1929 bubble peak. Likewise, actual 10-year market returns were substantially lower than expected returns in the 10-year period beginning in 1922, because the endpoint of that 10-year period was the 1932 market low.

You’ll see that same feature of “errors” across history. Actual 10-year market returns were substantially lower than expected returns in the 10-year period beginning in 1964, because the endpoint of that 10-year horizon was the 1974 secular valuation low. Actual 10-year market returns were substantially higher than expected returns in the 10-year period beginning in 1990, because the endpoint of that 10-year horizon was the 2000 bubble peak.

Put simply, these so-called “errors” contain information. It’s enormously tempting to imagine, at bubble highs, that glorious backward-looking returns, far greater than those previously implied by valuations, demonstrate that historical standards of value are outdated and obsolete. In their 1934 classic, Security Analysis, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd described the mood surrounding the 1929 market peak, observing that investors had abandoned their attention to valuations because “the records of the past were proving an undependable guide to investment.”

In truth, there was an enormous warning in the “error” between the returns investors were enjoying and the returns suggested by valuations. Presently, that same kind of “error” offers the same warning as those that misled investors to ignore valuations in 1929 and 2000.

It’s enormously tempting to imagine, at bubble highs, that glorious backward-looking returns, far greater than those previously implied by valuations, demonstrate that historical standards of value are outdated and obsolete. In 1934, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd described the mood surrounding the 1929 market peak, observing that investors had abandoned their attention to valuations because ‘the records of the past were proving an undependable guide to investment.’ For the moment, neither valuations nor arithmetic matter to investors either. As Galbraith observed, ‘As long as they are in, they have a strong pecuniary commitment to belief in the unique personal intelligence that tells them that there will be yet more.’

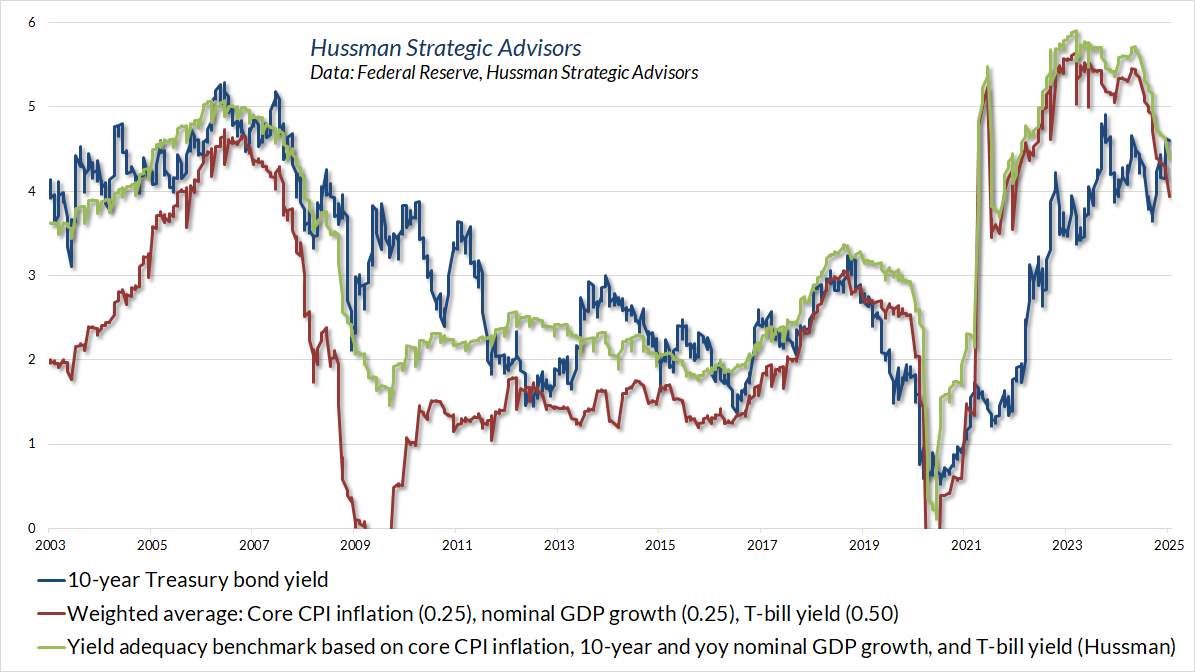

In the bond market, the most notable development in recent weeks is that, after a long period of yields that we’ve viewed as “inadequate,” 10-year Treasury yields have finally pushed to levels that we believe provide reasonable prospects of outperforming Treasury-bill returns. The chart below shows the 10-year Treasury bond yield compared to the simplest of the benchmarks we consider.

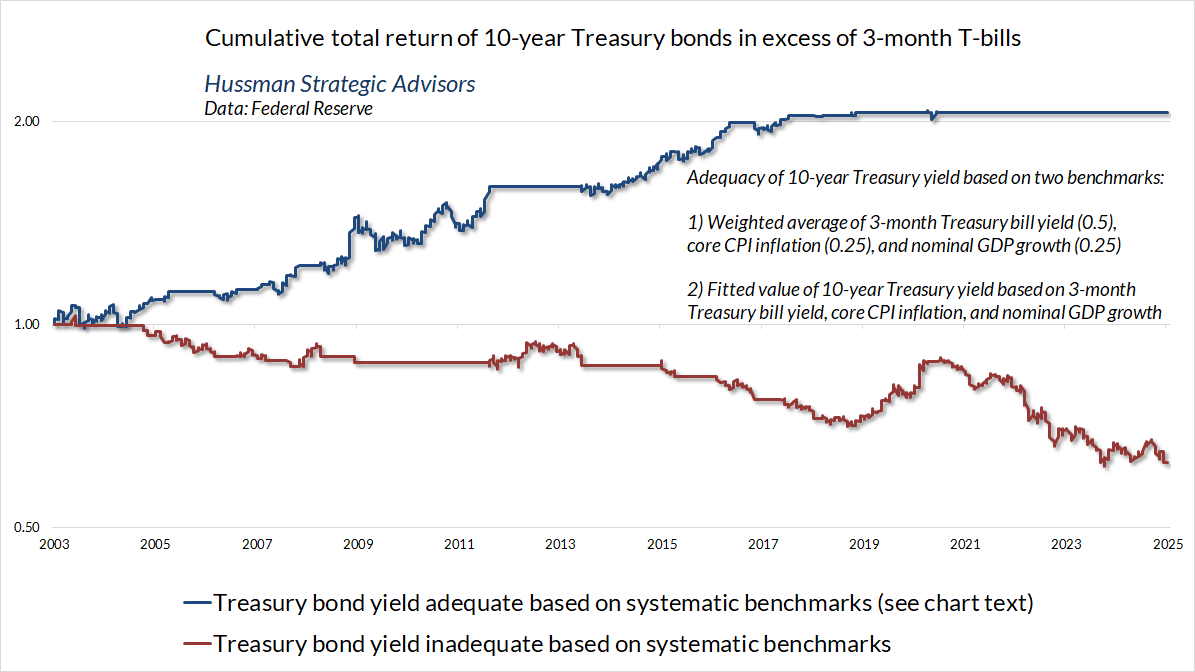

The chart below shows the total return of 10-year Treasury bonds, over-and-above Treasury bill returns, based on whether the prevailing 10-year yield has been adequate or inadequate based on these benchmarks.

The main update on precious metals shares here is that while we consider valuations to be reasonable, and weaker economic conditions (for example, an ISM Purchasing Managers Index below 50) tend to be better for gold stocks than strong economic conditions, we do consider the recently rising trend of interest rates to be a headwind. More favorable conditions for precious metals shares are likely to emerge when reasonable valuations and relatively weak economic conditions are joined by falling interest rates, even 10-year Treasury yields below, say, their level 6-months earlier.

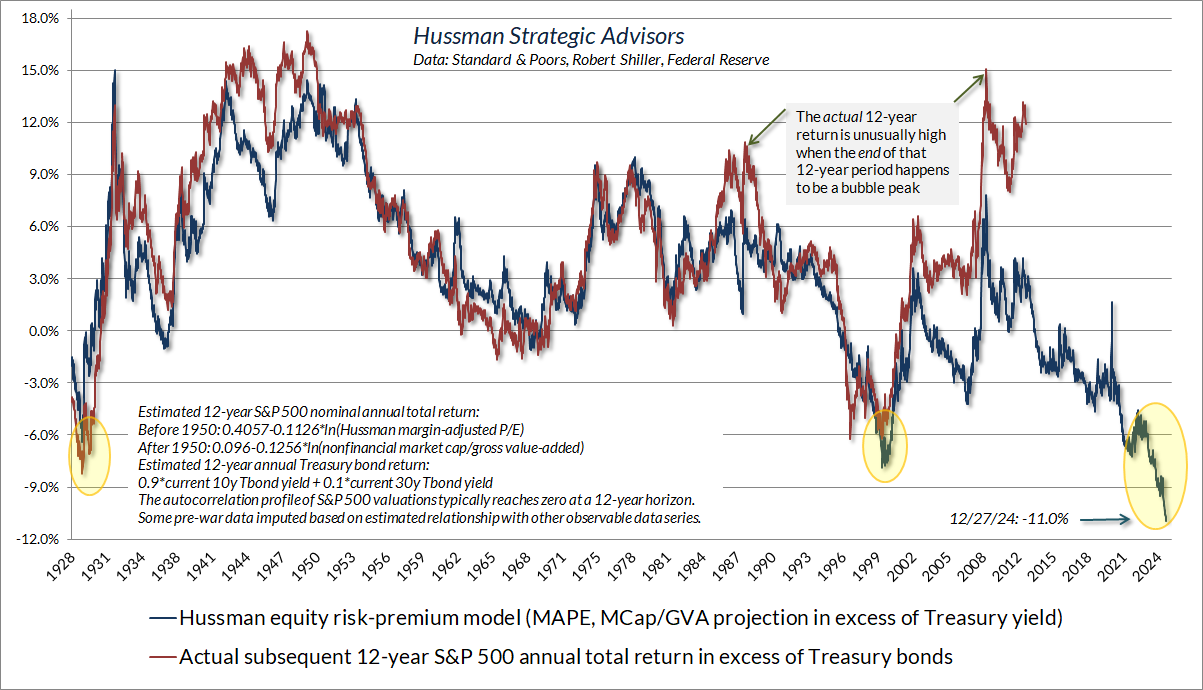

The difference between our estimates of likely 10-year S&P 500 total returns and 10-year Treasury returns – the “equity risk premium” – is currently the widest and most negative in U.S. history. I find it fascinating that so many analysts trot out risk-premium estimates without offering evidence – ideally a century of it – on how those estimates have been related to actual, subsequent outcomes. Investors looking for unsubstantiated verbal bullish reassurance can find this sort of thing easily enough.

As for historical evidence – with the emphatic reminder that these estimates say almost nothing about near-term return prospects – the chart below shows the present situation. The reason the estimated gap between expected equity and bond returns is so extreme is because stock market valuations are at record highs while 10-year bond yields are at what we view as historically adequate levels.

Again, as always, you’ll see “errors” in this chart, in this case reflecting valuation extremes at the endpoint of certain 12-year horizons. If we assume and rely on market valuations remaining at record extremes 12 years from today, we can also assume that actual equity returns in the coming 12 years, relative to bonds, may be better than our estimate below. Still, even the largest “error” in history would not push the resulting 12-year risk-premium above zero.

I realize that a shortfall of -11.0% versus bonds seems preposterous and implausible, though I haven’t been a stranger to seemingly preposterous and implausible estimates at the extremes of previous market cycles over the past 40 years. If one wishes to make the implications more tolerable, one can narrow the gap by several percent with heroic but not altogether impossible assumptions about profit margins and growth rates. Unfortunately, my impression is that one has to dispense with history altogether to garner more comfort than that.

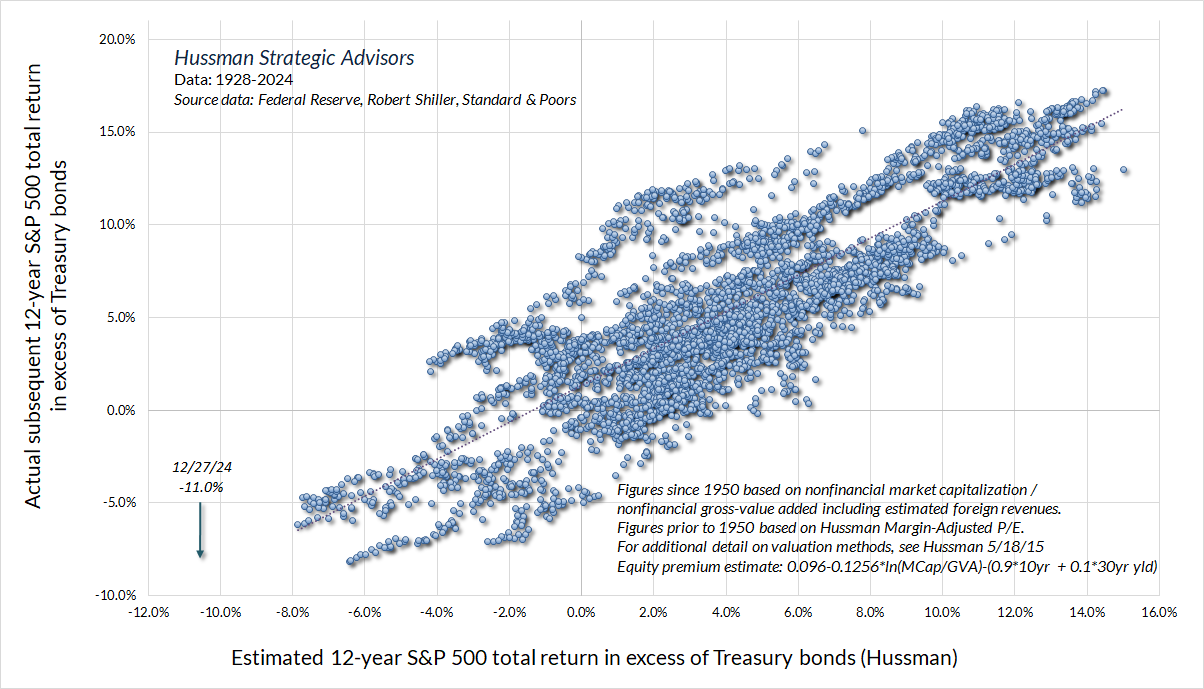

The chart below shows the same data as a scatterplot.

In short, revailing conditions imply among the most negative prospective returns and deepest potential losses in history. If you look carefully at the bubble, you can already see the collapse within it. Yet turn the TV to the business channel, and at nearly every moment, you’ll find another person with the “unique personal intelligence that tells them that there will be yet more.”

Still, as I’ve often noted, if rich valuations were enough to drive the market lower, it would have been impossible to reach extremes like 1929, 2000, and today. The ascent of valuations would have been stopped at lower levels. The only way to get here, at the outer reaches of history, was to advance, undaunted, through every lesser extreme. My impression is that it will end badly, not just because current valuations assume favorable developments, but because they require outcomes that are at odds with history, economics, and financial arithmetic. For more on that point, see the section on “New eras” in Ring Out Wild Bells.

It’s unclear how the psychology of investors will unfold in the coming weeks. Our current outlook is bearish, but as I noted earlier, we’re not presently inclined to amplify that should the market advance further. In any event, given that we align our investment positions with measurable, observable conditions as they change over time, no forecasts are required.

The Farmer

I have one life and one chance to make it count for something. My faith demands that I do whatever I can, wherever I am, whenever I can, for as long as I can, with whatever I have, to try to make a difference… God gives us the capacity for choice. We can choose to alleviate suffering. We can choose to work together for peace. We can make these changes – and we must.”

– Jimmy Carter

Those of you who know me well know I’ve had three great mentors in my life, all peacemakers. Two that I’ve been inconceivably blessed to call friends – Jimmy Carter, and Thich Nhat Hanh (a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, “Thay” for “teacher”) – and one, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, who was taken from this world when I was only 6, but who over the years became and remained one of the voices in my head and heart. Dr. King was friends with Thay and nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967. Thay’s continuation was three years ago. On December 29, at the age of 100, Jimmy went home.

At the center of everything Jimmy Carter did was his love of God, his commitment to human rights, and his unshakable belief in the dignity and value of every human being – regardless of race, country, religion, or wealth.

If you look in the mirror, you’ll see a reflection of yourself; a manifestation of yourself. That reflection isn’t you, but you can’t say it’s anything other than you. I think for Jimmy Carter, every human being was like that – a reflection of God; a manifestation of God. Jimmy Carter had no enemies. He might not admire everyone, but he harbored hatred toward no one.

Among the things I’ll remember most about Jimmy Carter were his solidity, wisdom, compassion, and principle – his ability to listen, to understand, to look at other human beings as equals, to love others, and to wage peace.

Thich Nhat Hanh often said “There is no way to peace. Peace is the way” – those without peace in themselves can do nothing to create peace in the world. What peace requires is for each side to have the capacity to see the suffering of the other, whether that suffering is born of injustice, fear, poverty, hatred, pride, or even misperception. If one has enough solidity in oneself to look deeply at the suffering of the other person, one sees better what to do, and what not to do, to promote peace. That doesn’t mean rolling over defenseless, compromising one’s own security, setting aside justice, or making dishonorable concessions. It does ask us to try on different shoes, and pause to understand. To do otherwise is to allow suffering to transform not into peace and reconciliation, but into endless cycles of violence and hatred.

Jimmy Carter’s capacity to see the human suffering on both sides of a conflict often made him an object of criticism by those unable to see beyond their own suffering, and whose concern for humanity extends to only one side. Because his eyes weren’t narrowed to the team colors of us and them, black and white, he didn’t shy away from criticizing policies that undermine or erode human rights. He didn’t hesitate to remind and urge enduring allies, and our own policy makers, toward their better selves. Nor did he tag those we might call “enemy” as anything less than human – looking instead at the causes and conditions of suffering on each side, and ways to achieve peace. I think Jimmy Carter saw those on the other “side” the same way Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King described, “No matter what he does, you see God’s image there. There is an element of goodness that he can never slough off.”

All those at war

Pray to obtain

God’s blessing,

It’s with those in pain– Jimmy Carter, A Battle Prayer

A great deal has been written about Jimmy Carter’s achievements, particularly the Camp David Accords, and his decades of philanthropic work after leaving office. Beyond those achievements, and my own remembrance of him, the aspects I feel compelled to add about President Carter are those that address the misperceptions about his presidency. There’s an undeserved parenthesis in the way that many people talk about Jimmy Carter. In my view, every aspect of his memory is an admirable one.

I think of Jimmy Carter’s term as President of the United States as the diligent work of a tenant farmer, on land owned by the people, harvesting seeds that – in many cases – he did not plant, and planting seeds that he could not stay long enough to harvest himself. Those who are incapable of recognizing what he inherited, and what he sowed, might criticize his work as a farmer. To me, despite the difficulties he often faced, our nation owes him a debt of admiration and gratitude – not only for what he has done since leaving office, but for so much of what he accomplished as President.

President Carter prepared the ground and planted the seeds that helped to end the Cold War and reestablish U.S. leadership – and at least until recently – an expansion of democracy in the world. As Daniel Fried, the former U.S. Ambassador to Poland observed, “Introducing human rights into US bilateral relations meant that the default Cold War policy that a reliably anticommunist government could be embraced and its authoritarian nature tolerated was no longer automatic… it meant fewer free rides for dictatorships. By elevating human rights in the mix of US-Soviet and US-Soviet Bloc relations, Carter put the United States on offense in the Cold War and on the side of the people of the region.” That shift helped to embolden democratic movements, beginning with the Solidarity movement in Poland and spreading to other Eastern Bloc countries in the decade that followed.

President Carter often expressed pride that not a single bomb was dropped, nor was a single bullet fired by the U.S. during his Administration. In the most fitting cover of the year in Time magazine, Jonathan Alter wrote of President Carter, “his leadership helped prevent at least five wars—in Panama, Israel, and Iran when he was president, and in Haiti and North Korea after he left office. After waging four wars in the first 25 years of Israel’s existence, the Egyptian army—the only force capable of destroying Israel—hasn’t fired on the state once in all the years since.”

Yet even as he elevated human rights in U.S. foreign policy, Carter also initiated investments to modernize and enhance our military preparedness, including funding and development of stealth technology, the M1 Abrams tank, and precision-guided munitions that were critical later during the Gulf War. In his words, “Our policy is based on an historical vision of America’s role. Our policy is derived from a larger view of global change. Our policy is rooted in our moral values, which never change. Our policy is reinforced by our material wealth and by our military power. Our policy is designed to serve mankind.”

Prior to the Carter Administration, the U.S. had a sparse presence in the Middle East, mainly through offshore naval positions. Nixon had relied heavily on Iran, then an ally under the Shah, to serve as the regional policeman. After the Shah was toppled in the Iranian Revolution, the U.S. allowed him entry for medical treatment, which provoked the Iran hostage crisis, led by students loyal to Khomeini. Though Carter had previously sought and received assurances from the Iranian Prime Minister that the embassy would be protected, Khomeini had consolidated power by the time of the seizure. As Carter wrote in his diary at the time, “Without the protection provided by the host government, it’s almost impossible to do anything if one’s people are taken.”

Carter immediately froze billions of Iranian assets. Thirteen hostages were released in November 1979, and Khomeini suggested that the others might be put on trial. Carter informed Khomeini that the “trial” of any remaining hostage would result in an immediate blockade of Iranian commerce, and that death or injury of any hostage would result in direct U.S. military action. Khomeini never made threats about the hostages again.

During the crisis, Carter authorized a rescue attempt by U.S. helicopters from carriers in the Arabian Sea. But those helicopters had limited experience in long-range operations in desert environments and encountered mechanical issues amid brownout conditions and sand kicked up by the rotors. Three helicopters became inoperable, and eight U.S. service members were lost in a collision during withdrawal. Among the only things people remember about the crisis is this failure to secure an early release or rescue, yet it was still Carter who directed the negotiation of the Algiers Accords through Warren Christopher, which led to the safe release of all of the hostages. That agreement was finalized just before he left office. It was also Carter who created the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (the precursor to U.S. Central Command) to respond to crises in the Middle East and Southwest Asia.

During the late-1960’s and early 1970’s, government deficits expanded as a result of the Vietnam War and Great Society programs, which destabilized confidence in the U.S. dollar. In 1971, Nixon abandoned the gold standard, suspending the convertibility of U.S. dollars for gold. By 1973, the Bretton Woods system of pegged exchange rates collapsed, as other nations objected to the “inordinate privilege” of the U.S., which was funding its growing deficits by issuing debt and (now unconvertible) currency, which foreign countries were forced to accumulate in order to prop up a fixed exchange rate with the dollar.

Nixon amplified the loss of confidence in the stability of the U.S. dollar with his appointment of Arthur Burns as Chairman of the Federal Reserve, who was widely criticized for yielding to Nixon’s pressure to maintain easy monetary policies for political purposes. The energy crisis that followed the 1973 OPEC oil embargo amplified the cycle of wage-price inflation that Carter inherited when he entered office.

When Burns’ term ended in 1978, Carter replaced him with G. William Miller for a brief period, and appointed Paul Volcker as Fed Chair in 1979, who broke the back of inflation essentially by restoring public confidence that the Federal Reserve would not passively accommodate deficits, nor tolerate persistent inflation. Carter also established the Department of Energy to address the energy crisis and bolster energy independence. He gradually phased out existing price controls on oil and gas that had been established during the Nixon Administration, encouraging domestic oil production. He also placed solar panels on the White House, to symbolize an “all of the above” approach to energy production. Some remain on display at the Smithsonian.

In contrast to the widening government deficit burden he inherited, Carter controlled the growth of government expenditures in both defense and non-defense areas, and the overall deficit narrowed as a share of GDP, despite large cost-of-living adjustments in Social Security outlays. He presided over the largest overhaul of the U.S. Civil Service since 1883, to reduce inefficiency and increase accountability. Meanwhile, Carter deregulated the airline, trucking, railroad, and telecommunications industries, in a way that reduced government controls on ticket prices, freight rates, routes, service offerings, and market entry, increasing competition while also maintaining consumer protections, safety standards, universal service, and antitrust oversight. A very different type of “deregulation” excites Wall Street today, precisely because it promises to remove such protections.

My impression is that the caricature of the Carter Administration as a “failed” presidency largely reflects the inflation problem that he inherited, and the insult to national pride from a hostage crisis that – given the military technology, helicopter capabilities, and on-the-ground presence that prevailed at the time – proved impossible to resolve through force without also losing the lives of U.S. diplomats and staff.

The habit of judging a risky or uncertain action by its outcome – rather than the quality of the decision, information, and conditions under which the action was taken – is what Annie Duke describes as “resulting.” The evaluation of Carter’s presidency by some critics seems to be a mixture of “resulting” inflation and the hostage standoff, while ignoring nearly every other accomplishment. Yet even here, it was Carter who broke the inflation spiral, through fiscal discipline and Volcker’s monetary discipline. And it was Carter who secured the lives and release of every hostage that was taken. In accordance with the terms of the Algiers Accords, the hostages were released on January 20, 1981 – though timed minutes after Carter left office, as something of a rebuke for Carter’s refusal to appease demands that he viewed as dishonorable.

Carter appointed more women and people of color to the Federal judiciary than every President before him combined. He also established the Department of Education, largely to improve equity in education. While states and local school districts establish curriculum and staffing, every state receives funds to support education of students with disabilities (IDEA), and to support students from marginalized socioeconomic backgrounds or suffer neglect. It also funds postsecondary education for children of low-income families through Pell grants and student loans. When people say they want to abolish the Department of Education, this is mainly what would be eliminated.

Carter was a model of ethics and public service, in stark contrast to the personal avarice and crony capitalism that seems to be accepted today as a fact of life. During his presidency, Jimmy Carter placed his assets and farm business in a blind trust, with the terms of the trust laid out to ensure “that he will not benefit financially from agricultural policy decisions that he may make as President,” and specifically instructing the Trustee “to arrange the assets of the trust so that no one should reasonably assert that actions as President were motivated by a desire to foster his own personal monetary gain or profit.” After several years of drought while in office, and because of his commitment to lease the land at a fixed price despite inflation that was spiraling even before his term, the farm business was in debt by the time Carter left office, and Jimmy and Rosalynn later sold it.

In the years since, both Jimmy and Rosalynn declined the sort of “speaking fees” that might have boosted their financial wealth. “That’s not what I want out of life,” he said. “We give money, we don’t take it.” Nevertheless, looking across his full and well-lived years, Jimmy was much like Harry Bailey described his brother George at the end of It’s a Wonderful Life – “the richest man in town.”

Jimmy and Rosalynn established the Carter Center in 1982, with the mission of waging peace, fighting disease, and building hope. The Carter Center is deeply involved in the relief of human suffering, through efforts in global health and disease eradication and control, including Guinea worm, trachoma, river blindness, lymphatic filariasis, and schistosomiasis. The Hussman Foundation has been a partner in those efforts for over 20 years, and we’ve enjoyed wonderful friendships with people who work for and support the Center. The Carter Center also has programs on Peace and Democracy and has been an observer of over 100 elections in more than 40 countries, to support their integrity and democratic processes. The Center is tireless in its efforts to promote human rights, conflict resolution, and the rule of law – despite the tendency of humanity to see only the suffering of their own side, and to deny the humanity of others.

Meanwhile, Rosalynn Carter spent decades as a leading advocate for people affected by mental health conditions. The Carter Center’s program on Mental Health Advocacy has trained scores of journalists, and helps to build public awareness, understanding, and resources for those facing mental health challenges. We worked with Rosalynn and her staff to establish the Carter Center’s first international mental health program in Liberia. She was one of the most kind, graceful, astute, and persevering people I’ve ever known.

Of Rosalynn, Jimmy wrote – “With shyness gone and hair caressed with gray, her smile still makes the birds forget to sing, and me to hear their song.”

In another poem, Jimmy wrote of “lovely euphemistic words,” that others used to describe the future without him – invoking visions of “friends, kinfolks, and pious pastors gathered round my flowery casket, eyes uplifted, breaking new semantic ground, by not just saying that I have passed on, joined my maker, or gone to the Promised Land, but saying the lamented fact in the best and gentlest terms, that I, now dead, have recently reduced my level of participation.”

I don’t see my friend and mentor as gone. He remains all around, in the immense good he’s done, the human suffering relieved because of his love for others, particularly the most neglected, the millions of lives around the world that he’s changed for the better, the extraordinary staff at the Carter Center dedicated to continuing his work, and the countless people whose lives are kinder, more generous, more principled, more caring, and more concerned about others because of Jimmy Carter.

At his inauguration, Jimmy laid his hand over a family bible, open to Micah 6:8 – “to act justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God.”

All of those were you.

Keep Me Informed

Please enter your email address to be notified of new content, including market commentary and special updates.

Thank you for your interest in the Hussman Funds.

100% Spam-free. No list sharing. No solicitations. Opt-out anytime with one click.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive news and commentary, at no cost, from Hussman Strategic Advisors, News & Commentary, Cincinnati OH, 45246. https://www.hussmanfunds.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact.

The foregoing comments represent the general investment analysis and economic views of the Advisor, and are provided solely for the purpose of information, instruction and discourse.

Prospectuses for the Hussman Strategic Market Cycle Fund, the Hussman Strategic Total Return Fund, and the Hussman Strategic Allocation Fund, as well as Fund reports and other information, are available by clicking Prospectus & Reports under “The Funds” menu button on any page of this website.

The S&P 500 Index is a commonly recognized, capitalization-weighted index of 500 widely-held equity securities, designed to measure broad U.S. equity performance. The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is made up of the Bloomberg U.S. Government/Corporate Bond Index, Mortgage-Backed Securities Index, and Asset-Backed Securities Index, including securities that are of investment grade quality or better, have at least one year to maturity, and have an outstanding par value of at least $100 million. The Bloomberg US EQ:FI 60:40 Index is designed to measure cross-asset market performance in the U.S. The index rebalances monthly to 60% equities and 40% fixed income. The equity and fixed income allocation is represented by Bloomberg U.S. Large Cap Index and Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Index. You cannot invest directly in an index.

Estimates of prospective return and risk for equities, bonds, and other financial markets are forward-looking statements based the analysis and reasonable beliefs of Hussman Strategic Advisors. They are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of the prospective returns of any of the Hussman Funds. Actual returns may differ substantially from the estimates provided. Estimates of prospective long-term returns for the S&P 500 reflect our standard valuation methodology, focusing on the relationship between current market prices and earnings, dividends and other fundamentals, adjusted for variability over the economic cycle. Further details relating to MarketCap/GVA (the ratio of nonfinancial market capitalization to gross-value added, including estimated foreign revenues) and our Margin-Adjusted P/E (MAPE) can be found in the Market Comment Archive under the Knowledge Center tab of this website. MarketCap/GVA: Hussman 05/18/15. MAPE: Hussman 05/05/14, Hussman 09/04/17.