Amygdalotomy: Surviving the Intentional Demolition of Warning Signs

John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

President, Hussman Investment Trust

May 2020

Contents

Amygdalotomy

Valuation review

Market internals and monetary policy

Inflation or deflation?

A government deficit always creates a surplus for somebody

How to ensure that public support benefits American families

On corporate welfare, bankruptcy, and bank failures

We begin with several propositions, all that will be demonstrated below, but that may be useful to include up-front in order to prime what follows:

1) One of the most dangerous forces currently threatening U.S. economic, financial, and public health is the intentional demolition of warning signs that would otherwise enhance survival.

2) Market lows associated with U.S. recessions have generally occurred at valuations that were about 40% of those prevailing today – and sometimes even less. If investors assume that valuations will never again approach historical norms, they must also accept that future investment returns will be dismal compared to historical norms. To say that “low interest rates justify high valuations in stocks” is also to say “low interest rates justify low future returns in stocks.” If one wishes to protect overvalued prices, one also has to accept meager long-term returns.

3) Investors should be careful to avoid the misconception that easy money always supports the market. The fact is that market outcomes are conditional on whether investor psychology is inclined toward speculation or toward risk aversion. This is best inferred directly from the uniformity or divergence of market internals. Despite the fact that the Fed eased the whole way down during the 2000-2002 and 2007-2009 collapses, investors have come to believe that Fed easing always supports stock prices. That’s the wrong lesson, and the re-education of investors is likely to be excruciating.

4) As long as the public has confidence in government liabilities, the Fed can do as much “quantitative easing” as it wants – buying government bonds and replacing them with base money – or vice versa, and it won’t change the underlying belief that those pieces of government paper are “good” – regardless of which form they take. Quantitative easing in itself does not produce inflation.

5) It is not simply currency creation that creates inflation, but currency creation for the purpose of financing government deficits, to such an extent that public confidence in government liabilities is destabilized. The inflationary consequences tend to be particularly severe when these deficits occur during “supply shocks” when production of goods and services becomes constrained for one reason or another.

6) These pieces of paper created by government, even if they were non-inflationary, are not just monopoly money. Each dollar represents a grant of purchasing power, allowing the receiver to obtain real goods and services produced by others. It matters who gets them – especially if they are granted free and without collateral – and for what purpose. Deficits created by the CARES Act are largely grants of purchasing power to those who receive them, and they have a profound distributional impact.

7) The announced plan of the Federal Reserve to “leverage” Treasury funding in order to purchase outstanding uncollateralized corporate bonds from investors is a wholly illegal violation of Federal Reserve Act Section 13(3), as well as CARES Act “Terms and Conditions” Section 4003(c)(3)(B), which “for the avoidance of doubt” applies 13(3) requirements to the use of public funds “including requirements relating to loan collateralization, taxpayer protection, and borrower solvency.” Uncollateralized corporate bonds do not serve as their own collateral. Moreover, there is no assurance that investors will use the proceeds to support those same companies, or even the U.S. economy.

8) The moment the government runs a “deficit,” there is absolute certainty that at least one other sector – households, corporations, or foreign countries – will run a “surplus,” in which the income of that sector will exceed its consumption of U.S. goods and services and net real investment (e.g. homes, buildings, capital equipment). The structure of the aid package affects which sector accrues this “surplus” (which in equilibrium, must ultimately be invested in the very government liabilities that created it).

9) Two policy features are essential to prevent public funds from being used for excess compensation, private profit, inventory accumulation, deferred expenses, or “new” payments by corporations to related parties and subsidiaries:

a) Set a “basic income” threshold that creates a uniform playing field across programs such as unemployment, PPP, and corporate grants, above which public funds would not subsidize.

b) For any company receiving public support, allow loan forgiveness only to the extent that the company shows an “adjusted loss,” after disallowing expenses any excess compensation paid to management or employees above their “basic income” amount, as well as any expenses incurred for unused inventory, prepayments, items that don’t represent 2020 operating costs, or increased total expenses versus prior years.

10) It was not “bankruptcies and bank failures” that contributed to the Great Depression, but rather “disorganized and piecemeal bankruptcies and bank failures.” What happened in the Depression was that bank depositors had no insurance, nor was there an FDIC to ensure rapid purchase-and-assumption of insolvent banks. So instead, the insolvent banks tried to call loans in, leading to a domino-like chain of disorganized failures and bank runs by uninsured depositors. It is not bankruptcy, but disorganized and piecemeal bankruptcy, that causes dislocations.

11) Emphatically, “bankruptcy” does not mean that the business of a company evaporates, nor do its assets or employees. Similarly, “bank failure” does not mean that depositors lose a dime. In both cases:

a) The assets and goodwill, along with most of the liabilities and payables – are typically acquired by another company, or the bankrupt entity is recapitalized, and the company, its employees, and its operations essentially continue on under new ownership.

b) Under the “depositor preference” provision of Title 12, Section 1821(11)(A) of U.S. banking law, bank depositors receive preference over any other general or unsecured senior liability of the bank. No depositor has ever lost a penny of their insured deposits (currently $250,000 of coverage per depositor per bank) since the FDIC was created in 1933, nor have bank restructurings cost the FDIC more than it has taken in as insurance premiums from banks.

c) Risk-taking stockholders and bondholders lose money, because they are supposed to lose money in these situations.

Amygdalotomy

In a wide range of animals, including humans, the ability to detect, observe, and immediately respond to the fear of other members is essential to survival. When a herd of gazelle run from a lion, it’s not because most of the gazelle have even seen the lion, but rather because they respond in sequence to the fear signals provided by nearby members. Some animals even respond to the behavior of other species. That essential survival response is mediated by a part of the brain called the amygdala.

In extreme cases, the fear response can lead to aggression and self-harm. One of the ways to remove the fear response is to surgically disconnect the amygdala. The procedure is known as an amygdalotomy. In mentally ill patients that experience such profound, unwarranted, and persistent fear that they become self-injurious and suicidal, amydalotomy is sometimes used as a last resort. It is not used in less severe patients, because the procedure itself makes the person more susceptible to risks that threaten survival, by blunting appropriate and adaptive responses to danger.

In my view, by aggressively intervening in the financial markets, at valuation levels that are still nowhere near run-of-the-mill historical norms, the Federal Reserve has performed an amygdalotomy on the investing public. The Fed has encouraged a maladaptive confidence that risk does not exist. This overconfidence of investors is itself a threat to their survival.

As Stanley Druckenmiller recently argued, much of the risk that the U.S. economy presently faces is itself the result of years of misguided Federal Reserve policy:

“Corporations overborrowed and overleveraged going into this. Corporations took their borrowing from $6 trillion to $10 trillion. In my opinion, this was all the result of free money, despite many, many opportunities to normalize from 2012 to 2020.

“The Fed is there to solve a liquidity problem, but is not in any way capable of solving a solvency problem. You have companies like airlines that because of the free money I talked about, they spent 97% of their free cash flow on corporate buybacks. It was common all over corporate America – financial engineering.

“Yes, it wasn’t their fault that coronavirus happened, but I’ve actually been saying for years, none of these companies are going to be able to survive in a recession, given the borrowing they’re doing, and it’s reckless.”

Public health note

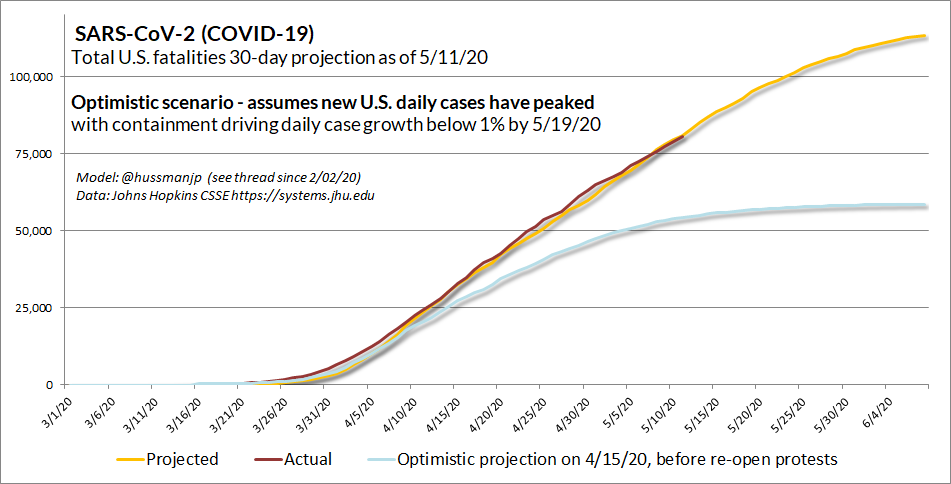

From a public health perspective, a similar blunting of the “fear response” early in the COVID-19 epidemic has also contributed to profound losses of both human life and economic activity in recent months. In particular, the initial response to the pandemic featured a wildly unwise attempt to minimize concern and limit containment actions, even after the U.S. had seed cases in major international travel hubs. As I noted on February 3, it was correct to follow the lead of the airlines by officially suspending travel from China, but little else was done during the first critical weeks, aside from assurances that “We have it totally under control. It’s going to be just fine.”

Despite the availability of effective tests from the World Health Organization, manufactured in Germany, the CDC was instructed to make its own tests, delaying our capacity to effectively trace and test people in contact with early seed cases. Containment efforts were delayed until, with U.S. cases growing into the thousands, a National Emergency was finally declared on March 13, yet with the same “this will pass” assurances. U.S. fatalities have now reached 90,000.

Even in late-March, a friend arriving overseas from Thailand said “I couldn’t step into a coffee shop in Bangkok without someone taking my temperature, but I waltzed through Seattle International, no questions asked.” It’s not at all surprising that the states with the highest case loads are also the states with major international airport hubs.

To be clear, my impression is that the weak and dismissive response to the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the critical early weeks is precisely what has resulted in recent U.S. fatalities and economic disruptions. Having initiated public health updates on this epidemic on February 2nd, when the U.S. had only 5 cases, it’s impossible to argue that “nobody saw this coming.” From the beginning, the main focus of those updates was on the urgency of containment efforts (see the SARS-CoV-2 thread of my personal Twitter feed for newer posts). The dismissive early response ultimately led to far more aggressive containment measures and dislocations than would have been required, had the imminent risk been appropriately addressed at the beginning.

On the notion of “reopening,” probably the most important comment I can add here is that projected fatalities and the “epidemic curve” are enormously sensitive to our own behavior. What people seem to think are “errors” and “changing forecasts” are largely a reflection of changes in our own containment practices.

If you’re going to increase your social contact, please understand that this virus primarily infects respiratory epithelia (cells in contact with outside air, which express ACE2 and TMPRSS2 on their surface, which the virus uses to gain entry). Please, wear a mask. Cloth is like low SPF sunscreen – it won’t protect you from everything, but it’s much better than nothing. Remember also that part of the reason for a mask is to protect others, since viral infectivity seems to be significant even two days before the emergence of symptoms. Hand washing is important, but my very strong impression is that aerosolized respiratory droplets from nearby breathing, and especially coughs, are a much larger risk. These can linger in the air with a half-life of over an hour, especially in enclosed indoor spaces.

Peak “the Fed has my back”

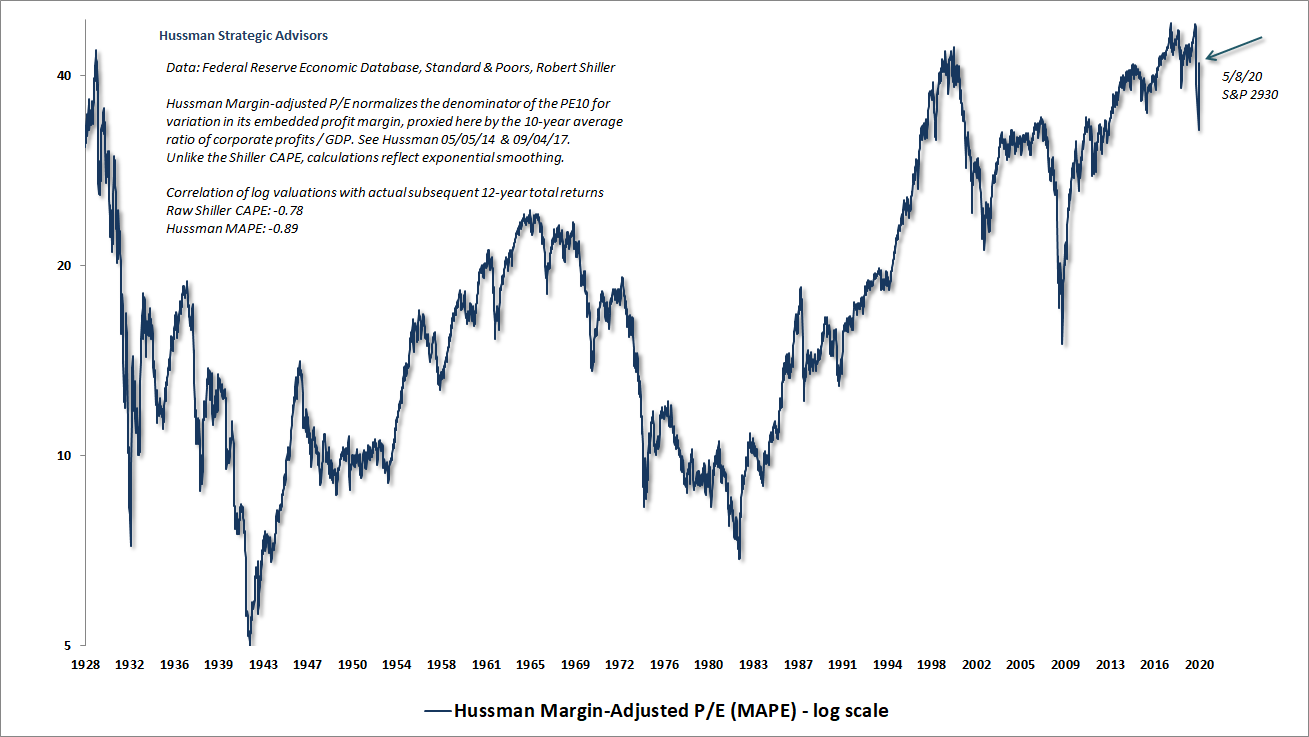

In recent weeks, despite employment and economic dislocations that now have the Great Depression as their only precedent, the S&P 500 has advanced to valuations that are within 13% of the most extreme levels in history, including 1929, on measures best correlated with actual subsequent 10-12 year market returns. Meanwhile, the total returns of largest junk-debt ETFs have rebounded within 6% of record extremes.

Emboldened by years of “buy the dip” reflex, and despite underlying risk-aversion, investors have found it impossible to resist taking one more bite at the apple. This enthusiasm reflects peak “the Fed has my back” confidence, at valuations that again imply negative S&P 500 10-year total returns, and despite market internals that remain more consistent with an overbought bear-market clearing rally than a sustained shift from risk-aversion.

The problem is that even if we assume COVID-19 will vanish tomorrow, and indeed that employment and economic losses never even happened, valuations are so far beyond historically durable levels that investors would still face zero long-term returns on a 10-12 year horizon, with steep full-cycle risks over the completion of the current market cycle.

Of course, the hallmark of “the Fed has my back” confidence is that investors have wholly ruled out the existence of market cycles, much less the possibility that valuations will ever again touch historically run-of-the-mill levels.

When it comes to buying overvalued assets, you don’t get to have your cake and eat it too. If you want to protect overvalued prices, you also have to accept meager long-term returns.

Yet even that is a problem. See, suppose you expect to receive a $100 cash flow a decade from today, and because interest rates are low, you’re willing to discount that future cash flow at a 0% rate of return. Well, on that assumption, it may very well be true that the “justified” price of that investment is $100 today. But if you actually pay $100 today for $100 a decade from today, you’re still going to get a 0% rate of return. Put simply, when people say “low interest rates justify high stock valuations” what they actually mean is “low interest rates justify low future stock returns.”

When it comes to buying overvalued assets, you don’t get to have your cake and eat it too. If you want to protect overvalued prices, you also have to accept meager long-term returns.

Valuation review

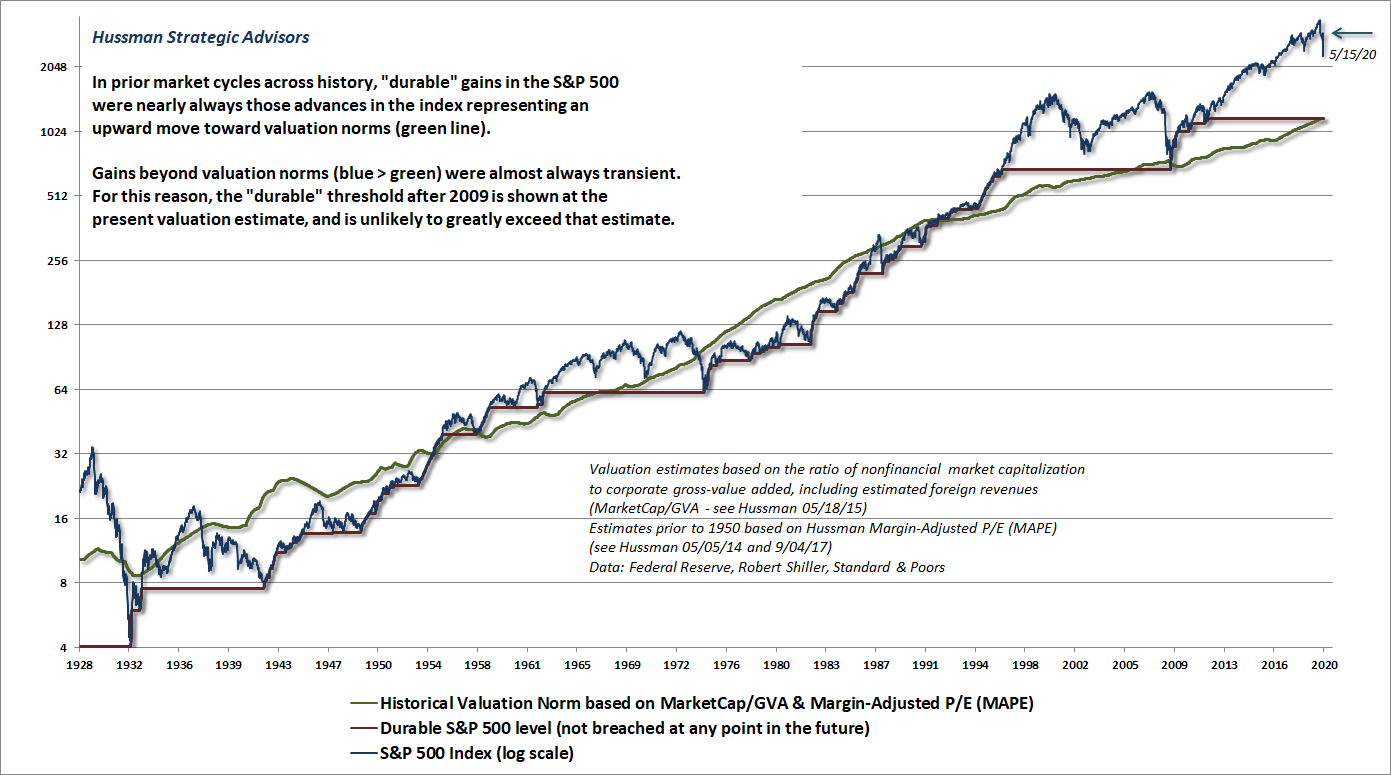

Over a century of market cycles, the valuation measures we find best correlated with actual subsequent S&P 500 total returns are a) nonfinancial market capitalization to corporate gross value-added, including estimated foreign revenues (MarketCap/GVA), and b) our Margin-Adjusted P/E (MAPE). Those correlations are 0.93 for MarketCap/GVA and 0.89 for the MAPE.

The green line in the chart below shows the level of the S&P 500 that would result in valuations consistent with long-term S&P 500 total returns of about 10% annually. The red line shows levels for the S&P 500 that have proven to be “durable” in the sense that the S&P 500 has not breached those levels at any point in the future. Notice that durable market advances are typically associated with advances toward the green valuation line, and that transient advances (that are typically surrendered over the completion of the market cycle, or future ones) are associated with market advances beyond that green valuation line.

There’s no question investors are looking “over the valley” in expectation of a “V” shaped recovery, and they are already chasing stocks, because recession lows are typically followed by bull markets. In that context, it’s worth remembering that market lows associated with U.S. recessions have generally occurred at valuations that were about 40% of those prevailing today – and sometimes even less. So yes, once the S&P 500 is down 60% or more, it will probably be reasonable to look “over the valley.”

It’s also important to recognize that high valuations aren’t always followed by an immediate market retreat (which is why we have to attend to the condition of market internals). But just as paying $100 today for a $100 payment a decade from now will give you a zero return, high valuations are invariably associated with below-average long-term market returns.

That’s why the total return of the S&P 500 (nominal, including dividends) since March 2000 has averaged just 5.2% annually, despite the recent market advance to the most extreme valuations in history. Conversely, it’s also why normal or below-average valuations have historically been associated strong long-term returns.

There’s no question investors are looking ‘over the valley’ in expectation of a ‘V’ shaped recovery, and they are already chasing stocks, because recession lows are typically followed by bull markets. In that context, it’s worth remembering that market lows associated with U.S. recessions have generally occurred at valuations that were about 40% of those prevailing today – and sometimes even less.

The chart below shows our Margin-Adjusted P/E (MAPE). At the 2930 level of the S&P 500, following a “clearing rally” from March lows, market valuations remain within 13% of single most extreme level in history, and continue to rival the 1929 and 2000 peaks. If current valuations provide an “opportunity” for investors, it’s not on the buy side.

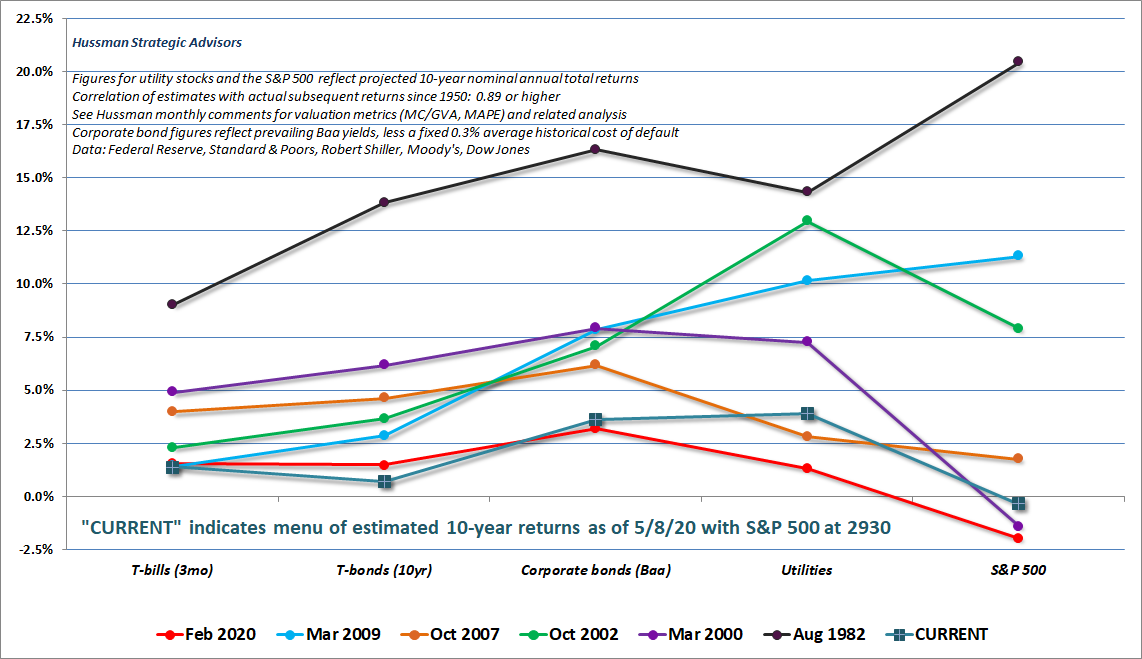

Presently, we estimate that the menu of options for passive investors is nearly the worst in U.S. financial history. The chart below shows our estimates for 10-year prospective returns for a range of conventional investment classes (each which has a correlation of 0.89 or higher with actual subsequent returns across history). The menu labeled “CURRENT” shows these projections as of early-May.

With regard to the current downturn, I expect that over the completion of this cycle, the S&P 500 will most likely lose roughly two-thirds of its value as measured from the February 2020 highs. Even that retreat would only bring the S&P 500 to historically pedestrian, run-of-the-mill valuations. Still, as noted in the next section, we will remain very flexible to shifts in our measures of “market internals,” because those shifts will chisel the intermediate-term path that the market may follow along the way.

Market internals and monetary policy

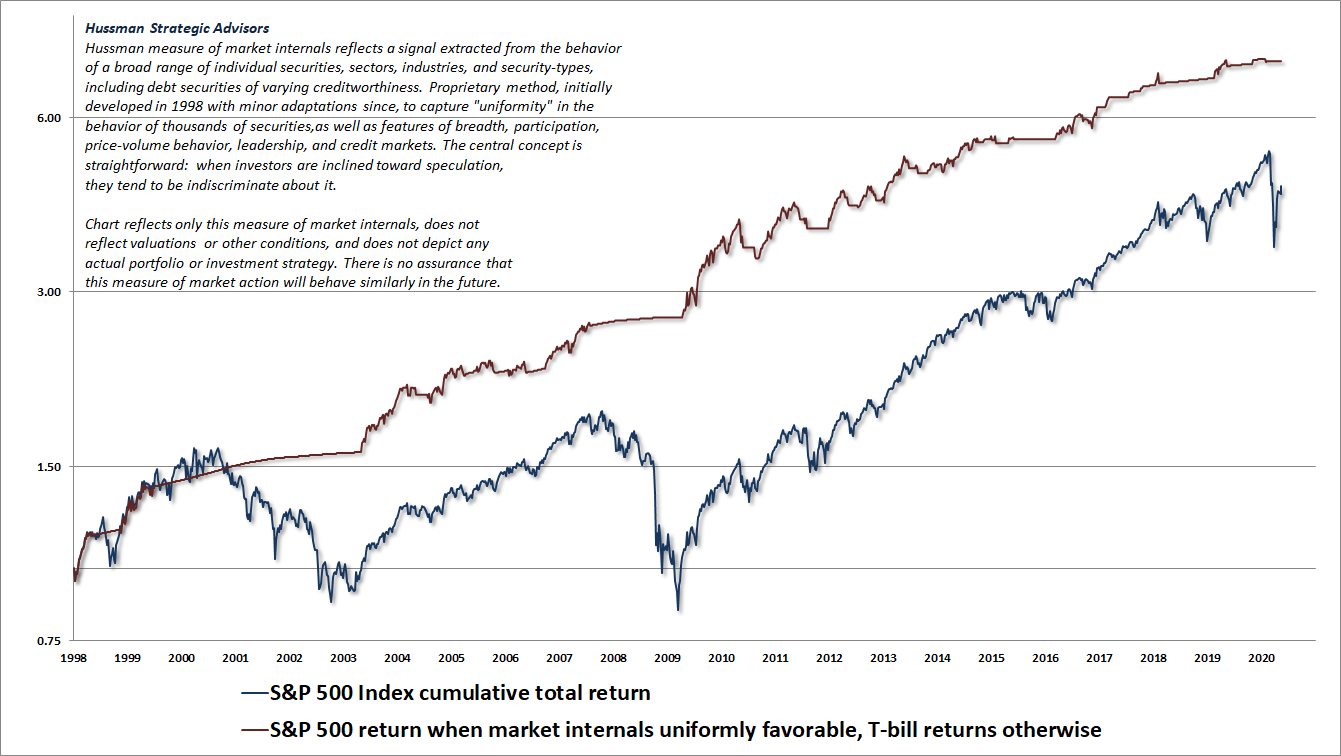

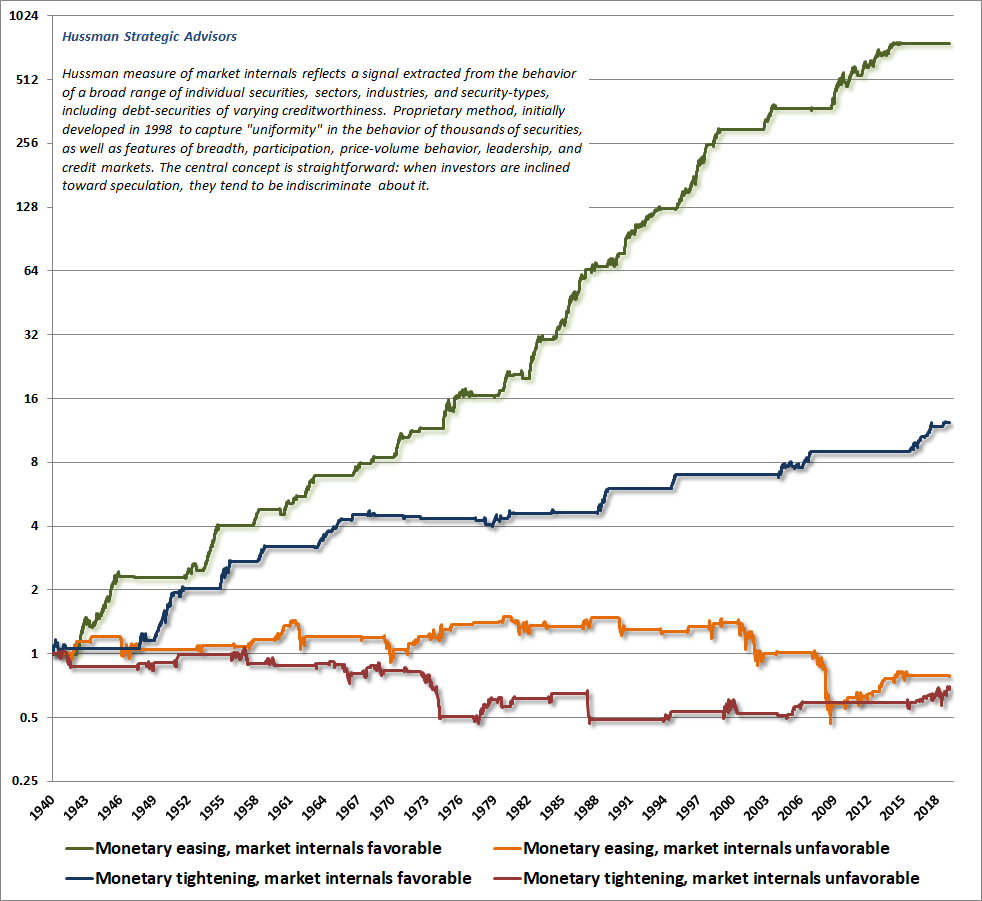

Investors have long forgotten that the S&P 500 lost half its value in 2000-2002, and even more in 2007-2009, despite the fact that the Fed eased aggressively the whole way down. Easy money only “works” to support prices if investor psychology is inclined toward speculation.

If investors have psychologically ruled out the potential for stock prices to go down, then even the lowest yielding stocks seem preferable to zero-interest liquidity. But once investor psychology shifts toward risk-aversion, investors consider not just the yield on stocks and other risky securities, but their potential for capital losses. In that environment, safe low-interest liquidity becomes preferable to outright losses, so creating more of the stuff isn’t sufficient to provoke speculation.

Monetary easing in itself is not enough. It’s important to directly ask whether investors are inclined toward speculation or toward risk-aversion. On that question, we find that the most reliable measure of that investor psychology is the uniformity or divergence of market internals across thousands of individual stocks, industries, sectors, and security-types, including debt securities of varying creditworthiness.

The chart below presents the cumulative total return of the S&P 500 in periods where our measures of market internals have been favorable, accruing Treasury bill interest otherwise. The chart is historical, does not represent any investment portfolio, does not reflect valuations or other features of our investment approach, and is not an assurance of future outcomes.

Our measures of market internals definitely include yield measures and credit spreads. But with regard to “liquidity,” it’s clear that market response to Fed policy is conditional on risk-preferences, which is best measured directly with internals. It’s important to understand that the entire total return of the S&P 500 in recent cycles, including most recent full cycle, has occurred when they’ve been favorable.

Monetary easing in itself is not enough. It’s important to directly ask whether investors are inclined toward speculation or toward risk-aversion. If investors have psychologically ruled out the potential for stock prices to go down, then even the lowest yielding stocks seem preferable to zero-interest liquidity. But once investor psychology shifts toward risk-aversion, investors consider not just the yield on stocks and other risky securities, but their potential for capital losses.

The accompanying chart is one that I shared last year, and shows how market internals and monetary policy interact in determining stock market outcomes. Notice that while monetary policy is highly effective in supporting stocks investors are indiscriminately willing to embrace risk, the market gets very little reliable support, even when the Fed is easing aggressively, when investors are inclined toward risk-aversion.

It’s enough to identify speculation vs. risk-aversion, but don’t assume that either has limits

I make it a point to openly discuss my error during the recent bull market, and how it was addressed in late-2017. I’ve included that discussion below. Those of you who have memorized it by now can skip two paragraphs.

As I’ve detailed extensively, both valuations and market internals performed beautifully in the recent complete market cycle, as they have historically. My error in recent years was due to a different consideration: my pre-emptive bearish response to “overvalued, overbought, overbullish” syndromes that had generally signaled a “limit” to speculation in prior market cycles across history. Because of their reliability across history, we prioritized those syndromes following our 2009-2010 stress-testing exercise against Depression-era data. In hindsight, amid the novelty of quantitative easing and zero-interest rate policy, our pre-emptive bearish response to those “overvalued, overbought, overbullish” syndromes turned out to be detrimental. No incremental adaptation was enough until I threw my hands up in late-2017 and completely abandoned the notion that it was still possible to define any “limit” to speculation.

Since then, our requirement has been straightforward: Regardless of how extreme valuations or other conditions might become, we will defer adopting or amplifying a ‘bearish’ investment outlook unless our measures of internals have explicitly deteriorated. Some conditions may be extreme enough to justify a neutral outlook, but a bearish outlook requires deterioration in internals, signaling that investors have shifted toward risk-aversion. That single requirement would have dramatically improved our experience in this half-cycle. It allows us to pursue a historically-informed, value-conscious, full-cycle investment discipline, while fully embracing the likelihood of future episodes of zero interest rates and quantitative easing, and even the possibility of negative interest rates, helicopter money, and other extraordinary policies.

Put simply, in late-2017, we became content simply to measure the presence or absence of speculation, based on the condition of market internals, and we abandoned the belief that speculation still had any well-defined “limit.”

The core of our investment discipline, particularly after our late-2017 adaptation, is fairly simple: The outlook is worst when neither valuations nor internals are in your favor. The outlook is best when you have support from both. Don’t use leverage if internals are negative. Don’t be a bear if internals are favorable. The appropriate response to monetary policy depends on the observable condition of market internals, which reflect whether investors are inclined toward speculation or risk-aversion. Everything else is finesse.

Investors should be careful to avoid the misconception that easy money always supports the market. The fact is that market outcomes are conditional on whether investor psychology is inclined toward speculation or toward risk aversion. This is best inferred directly from the uniformity or divergence of market internals. Despite the fact that the Fed eased the whole way down during the 2000-2002 and 2007-2009 collapses, investors have come to believe that Fed easing always supports stock prices. That’s the wrong lesson, and the re-education of investors is likely to be excruciating.

It’s called a “stock exchange” for a reason

One of the things that we sometimes hear, even from rather sophisticated investors, is that Fed liquidity somehow “spills over” into the stock market if the Fed creates enough of it. It’s a tempting concept, but it’s simply incorrect. See, every dollar that a buyer of stocks brings “into the market” goes “out of the market” in the hands of the seller of those stocks, the instant a transaction occurs. The stock market is a place where stocks change ownership from one individual to another. That’s why it’s called a stock exchange. Simultaneously, cash also changes ownership from one individual to another.

The fact is that every security that is issued – stock shares, bonds, and even base money (currency and reserves) created by the Federal Reserve – remains in existence, held by someone, in precisely the same form it was issued, until that security is retired. Money doesn’t go “into” our “out of” the market. Securities, including the Federal Reserve liabilities we call “money,” simply change hands.

Zero-interest base money (or low-interest base money, if the Fed pays interest to banks on their excess reserves) supports the stock market not by “spilling over” into the market, but instead by making the holder uncomfortable, and eager to get rid of it. Of course, in equilibrium, someone has to hold it at every point in time, so Fed liquidity is really just a stack of zero or low-interest “hot potatoes.”

I’ll say this again. The crucial thing to understand is that when investors are inclined to speculate, zero interest liquidity is an “inferior” asset, because even the lowest yielding alternative seems better than zero. On the other hand, if investors are inclined toward risk-aversion, they consider the possibility of capital losses, and unless valuations are low enough to offer significant long-term protection, safe liquidity is actually viewed as a desirable asset, and does nothing to support stocks.

We certainly can’t rule a continuation of extraordinary and misguided policies from the Federal Reserve. We’ve abandoned the idea that stupidity has any natural limit. What will matter enormously is whether those policies are accompanied by speculative investor psychology or risk-averse investor psychology. When the uniformity of market internals indicates that investors have adopted a robust willingness to embrace risk, then yes, a constructive or bullish response to Fed easing is likely to be most appropriate. The danger is in responding to Fed easing regardless of the surrounding context.

Though Fed easing is usually worth an obligatory short-term market pop, the most hostile situation an investor can face is a steeply overvalued market where investors have become inclined toward risk-aversion (as evidenced by ragged and divergent internals).

As for current market conditions, following an obligatory and now overbought short-term pop in response to Fed easing, the equity market remains steeply overvalued, while investors remain inclined toward risk-aversion (as evidenced by still ragged and divergent internals).

Valuations, internals, and the “plan”

Be careful to distinguish the level of valuations, which have been extreme for quite some time, from the consequences of overvaluation, which depend on surrounding market conditions. While valuations provide an enormous amount of information about long-term investment prospects, and likely downside risk over the completion of any cycle, the information from valuations is often entirely useless and even detrimental over shorter segments of the market cycle. The question isn’t whether valuations are useful, but when.

– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., October 2018

Having established, I hope, that the response of the market to Fed easing is dependent on the condition of market internals, we’re left with two primary conditions that affect the expected return/risk profile for the stock market. Valuations are the long-term consideration. Market internals capture the speculative or risk-averse psychology of investors over shorter horizons. Both of those factors have beautifully navigated complete market cycles over time, including the most recent one.

So from the perspective of our value-conscious, full-cycle investment discipline, the appropriate “plan” for navigating coming market conditions is this:

The most negative market return/risk outlook we identify emerges when extreme valuations are joined by deterioration in the uniformity of market internals, particularly if short-term market action is overbought as it has been in recent weeks. If market internals are negative, monetary easing is not enough to support a bullish investment outlook.

If market internals were to improve at current valuation extremes, we would still suspend our bearish outlook, and our view would shift neutral or possibly even “constructive with a safety net” depending on the surrounding market context. If market internals are favorable, even extreme “overvalued, overbought, overbullish” conditions are not sufficient to establish or amplify a bearish investment outlook.

More likely, a favorable shift in market internals will emerge at substantially lower valuations. As valuations retreat, long-term investment prospects will improve, but until market internals actually improve, even reasonable valuations should be accompanied by a moderate safety net, and leveraged positions should be deferred.

The most favorable market return/risk outlook emerges when a material retreat in valuations is joined by an improvement in the uniformity of market internals.

The core of our investment discipline, particularly after our late-2017 adaptation, is fairly simple: The outlook is worst when neither valuations nor internals are in your favor. The outlook is best when you have support from both. Don’t use leverage if internals are negative. Don’t be a bear if internals are favorable. The appropriate response to monetary policy depends on the observable condition of market internals, which reflect whether investors are inclined toward speculation or risk-aversion. Everything else is finesse.

Inflation or deflation?

In my view, the United States is already running what I’d describe as ‘cyclically excessive’ deficits. It’s not clear yet that public revulsion has kicked in, so in the near term, economic weakness seems more likely to depress inflation and interest rates than to aggravate them. But an economic downturn would almost certainly drive U.S. government deficits to unsustainable levels, which could increase the search for alternatives to bonds and currency, adding to the upward pressure we’ve started to see in gold prices.

– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., August 2019

I’ve often emphasized that just like these pieces of paper we call “stocks,” these pieces of paper we call money have an enormous psychological component to their pricing. In fact, if you spend a great deal of time with data, you’ll discover that the effort to model inflation as a stable function of money supply, output, unemployment, and other variables is among the most comical wastes of time you’ll ever undertake.

Much of my thinking on inflation is captured in my August 2019 comment, How To Needlessly Produce Inflation. What follows largely mirrors that discussion.

If you study substantial inflations, you’ll find that they typically emerged in the context of large government deficits coupled with supply shocks. Consider Germany in 1929. As France and Belgium invaded the German industrial area in the Ruhr, protesting workers went on a mass strike, and the German government decided to pay them anyway, despite the fact that their production had dropped sharply. This combination of events should ring bells. It certainly has in the U.S. gold market in recent months.

Government deficits are funded by creating pieces of paper – namely government bonds, or if the central bank buys those bonds, base money. If the public believes that the government has a credible ability to retire its liabilities, or at least keep them from growing at a rate that’s not too different from the growth rate of the real economy, then people may be entirely content to hold those pieces of paper without being revolted by doing so.

As long as the public has confidence in government liabilities, the Fed can do as much “quantitative easing” as it wants – buying government bonds and replacing them with base money – or vice versa, and it won’t change the underlying belief that those pieces of government paper are “good” – regardless of which form they take.

Quantitative easing doesn’t directly produce inflation, and whatever inflation we get will not be the result of QE. The policy may have an indirect effect on inflation by encouraging Congress to run larger deficits than it otherwise might. In any event, what inflation requires is public revulsion to government liabilities, and what produces public revulsion is the creation of government liabilities at a rate that destabilizes the expectation that those liabilities remain sound.

As economist Peter Bernholz has noted: “There has never occurred a hyperinflation in history which was not caused by a huge budget deficit of the state… In all cases of hyperinflation deficits amounting to more than 20 per cent of public expenditures are present.”

As long as the public has confidence in government liabilities, the Fed can do as much ‘quantitative easing’ as it wants – buying government bonds and replacing them with base money – or vice versa, and it won’t change the underlying belief that those pieces of government paper are ‘good’ – regardless of which form they take. What inflation requires is public revulsion to government liabilities, and what produces public revulsion is the creation of government liabilities at a rate that destabilizes the expectation that those liabilities remain sound.

Moreover, even the size of the deficit has to be placed in context. See, deficits regularly expand during recessions, and tend to contract during economic expansions. The public is sufficiently familiar with this tendency that large deficits during economic downturns rarely cause inflation pressure. Rather, I would assert that revulsion generally kicks in when deficits become what I’d call “cyclically excessive” – that is, persistently larger than one would expect, given the current point in the economic cycle.

Put simply, quantitative easing merely changes the mix of securities that the public holds. That in itself doesn’t create inflation. Historically, inflation has been provoked by government deficits that create new government liabilities at a “cyclically excessive” and unsustainable pace. Conversely, episodes of runaway inflation have regularly been ended by restoring public faith that fiscal and monetary policy have returned to a sustainable course.

So it’s not simply currency creation that creates inflation, but currency creation for the purpose of financing government deficits to such an extent that public confidence in government liabilities is destabilized. The inflationary consequences tend to be particularly severe when these deficits occur during “supply shocks” when production of goods and services becomes constrained for one reason or another.

In his analysis of major hyperinflations, Nobel economist Thomas Sargent (also my former dissertation advisor at Stanford) observed:

“In each case we have studied, once it became widely understood that the government would not rely on the central bank for its finances, the inflation terminated and the exchanges stabilized. We have further seen that it was not simply the increasing quantity of central bank notes that caused the hyperinflation, since in each case the note circulation continued to grow rapidly after the exchange rate and price level had been stabilized. Rather, it was the growth of fiat currency which was unbacked, or backed only by government bills, which there never was a prospect to retire through taxation.”

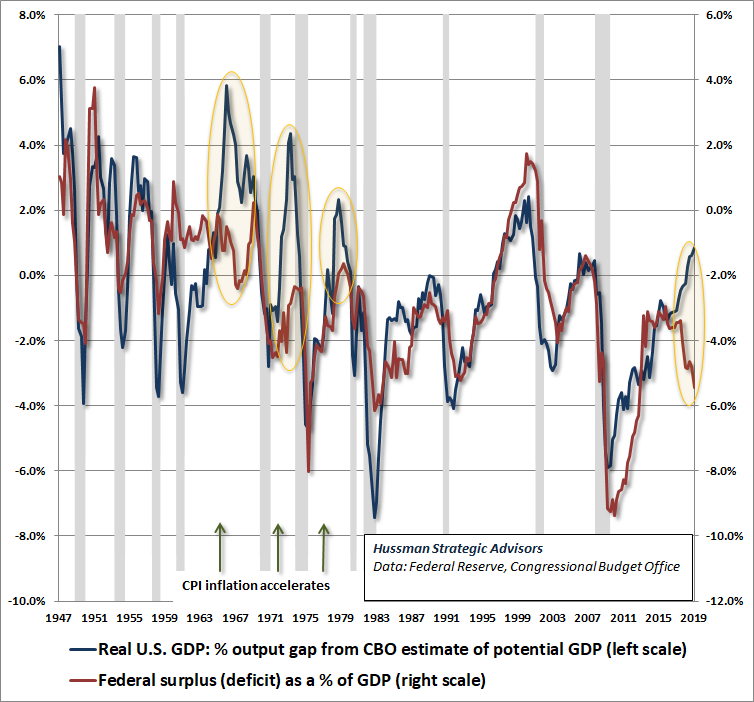

The chart below is from my August 2019 market comment, and shows the U.S. real GDP output gap (the difference between actual real GDP and potential real GDP, based on Congressional Budget Office estimates), along with the U.S. federal surplus or deficit, as a percentage of GDP. Notice that the two generally move together, reflecting a tendency toward smaller deficits or even surpluses during periods of economic strength, and larger deficits during periods of economic weakness.

Notice that there are a few periods when the U.S. economy was operating near full capacity (blue line near or above zero on the left scale), yet government deficits were significant and even expanding (red line well below zero on the right scale). These differences are circled in yellow. The notable feature of all of the prior instances is that they were exactly the points when the inflation rates accelerated. Even in 2019, the government deficit spending was already significantly out-of-line with the position of the U.S. economy.

Again, if the public believes that the government has a credible ability to retire its liabilities, or at least keep them from growing at a rate that’s not too different from the growth rate of the real economy, then people may be entirely content to hold those pieces of paper without being revolted by doing so.

Despite Milton Friedman’s dictum, inflation is not simply a monetary phenomenon. It is a fiscal one. When fiscal deficits become extreme, excessive money creation usually follows. But at its core, inflation reflects revulsion to holding government liabilities. It doesn’t actually matter whether these liabilities take the form of bonds or currency, because revulsion to those liabilities is enough to systematically devalue both of them.

It’s not simply currency creation that creates inflation, but currency creation for the purpose of financing government deficits to such an extent that public confidence in government liabilities is destabilized. The inflationary consequences tend to be particularly severe when these deficits occur during ‘supply shocks’ when production of goods and services becomes constrained for one reason or another.

Will inflation bail out a hypervalued stock market? Don’t bet on it. As I detailed in my February market comment, Whatever They’re Doing, It’s Not Investment (https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc200130/), the first casualty of inflation is market valuations. With the most reliable measures of market valuation presently about 2.5 times their historical norms, the CPI would have to more than double before the beneficial effects of inflation on nominal growth would outweigh the negative effects of inflation on market valuations. Until that happens, higher inflation will only make matters worse for investors.

The fact is that cash – short-term interest-bearing liquidity – has clearly outperformed the stock market during periods of rising inflation. Indeed, when the rate of inflation is rising, higher rates of inflation are typically associated with poorer stock market performance until market valuations are driven to historically depressed levels (after which the effect of inflation on nominal growth finally dominates).

With respect to deflation risk, the largest contributor on that front would be mass bankruptcies coupled with the avoidance of what I call “cyclically excessive” government deficits. In that environment, stocks would be wiped out, but risk-aversion among investors would likely encourage investors to treat cash as a safe haven, increasing the value of dollars relative to real goods and services (which is what we call deflation). That’s essentially what we observed during the Great Depression. We can’t rule out that prospect, but at present, the deficit and monetary spigots appear wide open.

A government deficit always creates a “surplus” for somebody

So this is interesting. If you work through the arithmetic of the national income accounts, you can prove to yourself that government deficits always show up as a “surplus” to some other economic sector: either households, or corporations, or foreign countries.

Moreover, in equilibrium – through millions of individual transactions with no necessary objective to achieve this result – it must be true that this “surplus” is identically equal to, and is used to purchase, the government bonds that the Treasury issues (or base money that the Fed creates) to finance that government deficit.

One way we can write the national income accounting identity involved here is:

Government consumption expenditures, net investment, and transfer payments – Government tax revenue = Household after-tax income not spent on consumption or real net household investment + Undistributed after-tax corporate profits not used for real net corporate investment + Foreign income due to the U.S. trade deficit (i.e. Imports – Exports)

Again, that’s not a theory. It’s an accounting identity.

The moment the government runs a “deficit,” there is absolute certainty that at least one other sector – households, corporations, or foreign countries – will run a “surplus,” in which the income of that sector will exceed its consumption of U.S. goods and services and net real investment (e.g. homes, buildings, capital equipment). Ideally, we can sustain as much domestic consumption and investment as possible. In any event, we’re going to be subsidizing a surplus for somebody. It would best be American families.

The worst outcome for the economy is for the government to save less by running a deficit, and for other sectors to save less as well. In that situation, as aggregate saving collapses, U.S. gross domestic investment must collapse as well. This is a severe recession/depression scenario. That’s not a theory. It’s an identity in the same way that 2=2, because “investment” and “saving” comprise the same thing: unconsumed output (even if that output represents unintentional “inventory investment”).

It’s better, at least, for the government to save less by running a deficit, and for households and corporations to “save more” but without cutting real household and corporate investment. That’s basically the scenario that Keynesian economics is based on. Keynes assumed that in an economic downturn, a “liquidity trap” can emerge where even low interest rates don’t stimulate new investment, so he advocated government deficits to fill the void.

The General Theory wasn’t quite “economics” in the sense that Keynes had little concern about whether scarce resources were allocated productively, and didn’t consider the idea of “scarcities” at all, but in an accounting sense, Keynes was right that if gross investment is “stubborn,” government deficits can offset the negative economic effect of increased attempts at private saving.

The best situation is for the government to save less by running a deficit, and for both household and corporate investment to actually increase. In that case, you get growth in economic output and incomes sufficient for new private savings to offset the government deficit.

The moment the government runs a ‘deficit,’ there is absolute certainty that at least one other sector – households, corporations, or foreign countries – will run a ‘surplus,’ in which the income of that sector will exceed its consumption of U.S. goods and services and net real investment (e.g. homes, buildings, capital equipment). Ideally, we can sustain as much domestic consumption and investment as possible. In any event, we’re going to be subsidizing a surplus for somebody. It would best be American families.

Unless we’re headed for a depression scenario, you’re likely to see saving increase in one or more sectors of the economy. Ideally, much of the deficit spending will be repaid as loans, and the portion that’s forgiven will be appropriately tied to actual economic loss, rather than directly subsidizing extraordinary incomes and corporate profits. The next section discusses how policymakers can encourage that outcome.

How to ensure that public support benefits American families

Probably the most critical thing to remember about government spending and economic rescue packages is that every one of those dollars is a grant of purchasing power, allowing the receiver to obtain real goods and services produced by others in the economy. It’s critically important who gets those dollars – those claims on output – and to ensure that public spending isn’t used to artificially boost corporate profits, supplement extraordinary incomes, or bail out speculative losses.

This isn’t just monopoly money. Even if these dollars could be printed with absolutely no effect on long-term inflation, they are still claims to real goods and services produced by others. They are a grant of purchasing power to those who receive them. They have a profound distributional effect even if they come hot off of a printing press.

The closer we can get Federal rescue funds to the very entry point of the circular flow – supporting individual basic incomes, contractual payments like rent and mortgage obligations of families, and fixed obligations of businesses experiencing actual economic damage – the closer these economic support policies will hit their mark. The essential focus here is on current cash flows, and using public funds to create a safety net of basic income that will feed directly into the chain of subsequent economic transactions.

Policies that directly support household investment and capital investment are also important. Note the word “directly” here. We already know that furloughed workers are suddenly having difficulty securing mortgage loans, and that companies are pulling back on capital spending. Allowing homebuyers furloughed since, say February, to qualify for FHA loans on the basis of their prior income seems far more reasonable than allowing the Fed to purchase junk debt that isn’t even collateralized by property. Likewise, providing investment tax credits for 2020 capital spending, and allowing immediate expensing of new capital investment, would be wholly appropriate policies to boost corporate investment.

Be careful to distinguish between real production-function “Capital” from financial market investment security “capital.” There is an enormous difference between supporting “Capital” and supporting “capital.” The U.S. tax code already makes investment spending deductible over the life of the asset, so it already eliminates the taxation of “Capital.”

In contrast, using public money to boost financial “capital” – like bailing out secondary markets, protecting unsecured bondholders from losses, and treating a dollar of financial market profits as sacrosanct – as if it’s somehow more worthy of loving care and feeding than a dollar of wage income – simply disfigures the word “Capital” in order to benefit wealthy individuals, with only indirect effects on real productive investment.

This isn’t just monopoly money. Even if these dollars could be printed with absolutely no effect on long-term inflation, they are still claims on real goods and services produced by others. They are a grant of purchasing power to those who receive them. They have a profound distributional effect even if they come hot off of a printing press.

One of the most egregious examples in recent weeks is the misguided Federal Reserve experiment of buying low-grade corporate debt from investors in the secondary market. This ridiculous (and as I detailed last month, illegal) policy puts the public in first-loss position behind even the most subordinated bondholder, and uses public funds to take on years, and even decades, of future cash flows, along with their price risk.

Leveraged purchases of uncollateralized corporate bonds and junk debt, which carry the risk of both price loss and default without recovery, amount to an abuse of public funds and a violation of Federal Reserve Act Section 13(3) collateral requirements and taxpayer protections. Uncollateralized debt doesn’t serve as its own collateral. In the event of default, it’s gone, and given the enormous reliance on “covenant lite” structures during the recent credit bubble, the recovery rates are likely to be abysmal. What’s striking is that the Fed and the Treasury have concocted this abuse directly in violation Section 4003(C)(3)(B) of the CARES Act, which explicitly prohibits it:

4003(c)(3)(B): FEDERAL RESERVE ACT TAXPAYER PROTECTIONS AND OTHER REQUIREMENTS APPLY. – For the avoidance of doubt, any applicable requirements under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, including requirements relating to loan collateralization, taxpayer protection, and borrower solvency, shall apply with respect to any program or facility described in subsection (b)(4).

Many of these bonds were destined to fail long before the world ever heard of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. For companies at risk because of legitimate effects of the epidemic, the most appropriate use of public funds is to provide loans, secured by collateral, to cover current debt-service obligations. This would create the least distortion in the circular flow of economic activity.

It is a wild violation of public trust to simply relieve investors of risk by prepaying years of future interest and principal, near the most extreme valuations and lowest discount rates in the history of the U.S. financial markets. Meanwhile, there’s absolutely no assurance that the proceeds of Fed bond purchases will be used by investors to make loans to those same companies, or even that the proceeds will be used toward spending that supports the circular

flow of productive economic activity.

Linking loan forgiveness to actual economic damage

With regard to loans, forgiveness should be based on actual economic damage. If you weren’t damaged, you shouldn’t be receiving public money. How do you ensure that? It’s actually fairly straightforward.

a) Set a “basic income” threshold that creates a uniform playing field, regardless of whether an assistance program involves unemployment compensation, payroll protection program (PPP) loans, or even loans to large corporations. A reasonable model might be some minimum income level, plus some percentage of an individual’s median payroll income over the past 3 years, with the basic income capped at, say, one or two times U.S. median personal income, above which public funds would not subsidize.

b) Then, for any company receiving public support, loans would be forgiven only to the extent that the company shows an “adjusted loss.” Adjusted loss meaning that one would examine the company’s net income or loss for 2020, and then disallow from expenses any excess compensation paid to management or employees above their “basic income” amount, as well as any expenses incurred for unused inventory, prepayments, items that don’t represent 2020 operating costs, or expenses in excess of say, the prior 3-year high. If the company still has a loss after those adjustments, then fine, a portion or the entirety of the loan could be forgiven.

That sort of structure would basically prevent public funds from being used for excess compensation, private profit, inventory accumulation, deferred expenses, or “new” payments to related parties and subsidiaries.

Don’t misunderstand. It will be great if various U.S. companies prosper in 2020 because of customer demand for their products. Just don’t ask for public funds and loan forgiveness to directly subsidize those profits, or dividends, or stock repurchases, or deferred expenses, or the excess compensation of executives. That’s just nutbars.

First principles

It’s worth repeating some of the first principles discussed in last month’s comment:

1) Equal treatment – I’m not exactly sure how equity is served by paying employees up to $99,000 if they are kept on the payroll, whether they are working or not, but paying far less if they are on unemployment. In my view, this is a high-income subsidy. My impression is that it’s best to standardize these levels more uniformly (possibly as a minimum basic income plus some fraction of prior income in excess of that minimum). There should also be a cap on the amount of the income subsidy. Josh Hawley (R, MO) proposes using the median U.S. income as a cap.

2) Economic damage – Beyond income support to individuals, the most pressing obligations of businesses include mortgage/lease obligations, net interest obligations, utilities, and other fixed expense. Forgiveness of loans on this basis should be available to companies that experience an actual loss, adding back any extraordinary salaries. So at the end of the year, for example, you take the actual P&L, add back whatever amounts were paid to employees above the “standardized” compensation (above), and you forgive the loan only to the extent that the business experienced actual economic damage. Emphatically, if a company has a profit, or its executives are drawing salaries above the capped income subsidy that’s available to other Americans, the public shouldn’t be paying toward it.

3) Prohibition of using public money to bail out private securities losses. This is really where Federal Reserve activity can be insidious, because if it’s allowed to buy private securities like stocks and bonds, private investors are simply being bailed out at public expense. Not only is that wildly inefficient from an economic standpoint (it does nothing to ensure that the funds have broad economic benefit for workers or productive activity), but it’s also wildly inequitable, since the holders of these securities are highly concentrated among wealthy Americans.

4) Use of existing structures rather than novel ones, wherever possible. It’s not clear to me that a broad expansion of unemployment insurance, albeit with different formulas isn’t superior to novel programs like paycheck protection and other programs with far less certain implications for equity or abuse (again, as far as formulas go, I’m inclined toward minimum basic income plus some modest fraction of prior income in excess that minimum). The IRS could also administer support through existing SSN (individuals) and EIN (businesses) registrations, and would be most capable of applying criteria related to loan forgiveness or recovery.

On corporate welfare, bankruptcy and bank failures

Probably the dumbest line I’ve read over the past month is “When banks fail, people lose their savings.”

Let’s be very clear about this, at the very beginning of this economic downturn. It was not “bankruptcies and bank failures” that contributed to the Great Depression, but rather “disorganized and piecemeal bankruptcies and bank failures.” What happened in the Depression was that bank depositors had no insurance, nor was there an FDIC to ensure rapid purchase-and-assumption of insolvent banks. So instead, the insolvent banks tried to call loans in, leading to a domino-like chain of disorganized failures and bank runs by uninsured depositors. That’s not how the economic system works today.

It may be helpful to know that under the “depositor preference” provision of Title 12, Section 1821(11)(A) of U.S. banking law, bank depositors receive preference over any other general or unsecured senior liability of the bank. No depositor has ever lost a penny of their insured deposits (currently $250,000 of coverage per depositor per bank) since the FDIC was created in 1933, nor have bank restructurings cost the FDIC more than it has taken in as insurance premiums from banks.

I think very few people know this, or at least they don’t appreciate it. The FDIC has not cost the American people a dime.

– Warren Buffett, May 2020

You’re going to hear a lot of fearmongering about “bankruptcy and bank failures” aimed at using public funds to bail out investors in the stock and bond markets, who properly enjoy the potential returns, but should also bear the potential risks, of those investments.

Emphatically, “bankruptcy” does not mean that the business of a company evaporates. Consider a large U.S. airline company. The asset side of the balance sheet might be 70% property, plant, and equipment, 15% cash and investments, and 15% goodwill and other assets. The liability side of the balance sheet might be 20% equity capital, 30% debt, 10% pension and tax liabilities, 20% lease liabilities, and 20% payables and other short-term liabilities.

If the airline goes bankrupt, the planes don’t vanish, nor do all those valuable assets and goodwill. What actually happens is that part or all of the equity capital gets wiped out, along with some of the subordinated debt, and the rest of the company – the assets and goodwill, along with most of the liabilities and payables – are either acquired by another company, or the bankrupt entity is recapitalized, and the company, its employees, and its operations essentially continue on under new ownership.

Indeed, United, American and Delta have all been through bankruptcy, and countless smaller airlines have been acquired by, or merged into, existing ones as part of bankruptcy-related transactions.

Now consider a large U.S. bank. The asset side (especially given the amount of bank reserves the Fed has created in recent years) might be 50% cash, liquid assets, and security investments, 40% commercial and industrial loans, and 10% goodwill and other assets. The liability side of the balance sheet might be 10% equity capital, 30% debt, and 60% in checking, savings, and time deposits of customers.

If the bank becomes insolvent, the assets don’t vanish, nor do the bank deposits of customers. What actually happens is that the bank goes into receivership (rather than bankruptcy) with a nearly immediate “purchase and assumption” where another bank takes on all of the insolvent bank’s FDIC insured deposit liabilities, along with some of the assets and a cash payment from the FDIC. The insolvent bank’s equity capital gets wiped out, along with some of debt, and the rest of the assets are gradually sold by the FDIC. In general, the insolvent bank’s employees and operations continue under new ownership, and depositors just see a different bank name on their statements.

As I observed a decade ago amid the global financial crisis:

“The only reason that bank ‘failures’ in the Depression (and the ‘failure’ of Lehman) were problematic is that the institutions had to be liquidated in a disorganized, piecemeal fashion, because there was no receivership and resolution authority that could cut away the operating entity and sell it as a ‘whole bank’ entity ex-bondholder and -stockholder liabilities. I put ‘failure’ in quotations because there is a tendency to think of such events as something to be avoided even at the cost of public funds.”

Why did we do the bailouts? It was all about the bondholders. They did not want to impose losses on bondholders. They’re supposed to take losses.

– Sheila Bair, FDIC Chair, 2006-2011

One might protest, “This epidemic came out of the blue. Even if bankruptcy and bank failures only impose losses on stockholders and bondholders, why do they ‘deserve’ to lose anything?”

The answer is that they deserve to lose because they are precisely the ones who willingly bear these risks, and also enjoy the potential rewards in a free enterprise economy. They particularly deserve to lose to the extent that their behavior prior to this crisis was both speculative and reckless. As Edwin LeFevre wrote after the Great Depression:

“The reason why the stock market must necessarily remain the same is that speculators don’t change; they can’t. They could see no top early in 1929 and they could see no bottom late in 1931. Shrewd business men who wouldn’t sell absurdly overpriced securities would not buy, two years later, underpriced stocks and bonds. The same blindness to actual values was there, only that while the heavy black bandage was greed in the bull market, it was fear in the bear market. Reckless fools lost first because they deserved to lose, and careful wise men lost later because a world-wide earthquake doesn’t ask for personal references. Nevertheless, there is a general belief that the wise rich escaped punishment – as usual.”

A compassionate society has both economic reason and ethical responsibility to provide a social safety net to its most vulnerable members. It is an act of both economic insanity and ethical corruption to provide a financial safety net to its most reckless speculators.

Geek’s Note

Here’s a quick explanation of why government deficit spending always ends up as the retained income of either households, corporations, or foreign countries.

There are two basically equivalent ways to define U.S. economic activity. One is based on categories of output:

National output = Consumption + Investment + Government spending + Exports – Imports

“Investment” here means tangible gross private domestic investment in things like homes, equipment, office buildings, and factories, as well as accumulation of inventories (whether intentional or unintentional), and replacement of depreciated fixed capital. “Government spending” here means government consumption expenditures and gross investment (e.g. roads), and does not include transfer payments to individuals because they don’t represent output.

The other definition is based on categories of income, which we can simplify as:

National income = Household after-tax income + Undistributed after-tax corporate profits + Government tax revenue – Depreciation of fixed capital

“Household income” here does include transfer payments from the government, because payments like Social Security and unemployment are sources of income. The way I’ve written this, household income also includes dividends received from corporations. Household and corporate income here also includes net interest income and net rental income received by each, and I’ve moved the taxes they pay to the government revenue category.

Now, aside from a small statistical discrepancy: National output = National income + Depreciation of fixed capital (i.e. replacement investment). So subtracting depreciation of fixed capital from both sides (which turns gross investment to net investment) we get:

Consumption + Net private domestic investment + Government consumption expenditures and net investment + Exports – Imports = Household after-tax income + Undistributed after-tax corporate profits + Government tax revenue

If we subtract out the consumption and investment spending of each sector, we arrive at:

Government consumption expenditures, net investment, and transfer payments – Government tax revenue = Household after-tax income not spent on consumption or real net household investment + Undistributed after-tax corporate profits not used for real net corporate investment + Foreign income due to the U.S. trade deficit (i.e. Imports – Exports)

Finally, since you’ve hung in all the way to the end of this tome, this 90-second video from John Cleese wraps things up, with a full overview of the amygdala and general brain function.

After extensive research and endless nights in my lab, I present to you the most comprehensive and absolutely serious presentation on the brain and its functions to human health. pic.twitter.com/nKHr10YaP6

— John Cleese (@JohnCleese) May 17, 2020

Keep Me Informed

Please enter your email address to be notified of new content, including market commentary and special updates.

Thank you for your interest in the Hussman Funds.

100% Spam-free. No list sharing. No solicitations. Opt-out anytime with one click.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive news and commentary, at no cost, from Hussman Strategic Advisors, News & Commentary, Cincinnati OH, 45246. https://www.hussmanfunds.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact.

The foregoing comments represent the general investment analysis and economic views of the Advisor, and are provided solely for the purpose of information, instruction and discourse.

Prospectuses for the Hussman Strategic Growth Fund, the Hussman Strategic Total Return Fund, the Hussman Strategic International Fund, and the Hussman Strategic Allocation Fund, as well as Fund reports and other information, are available by clicking “The Funds” menu button from any page of this website.

Estimates of prospective return and risk for equities, bonds, and other financial markets are forward-looking statements based the analysis and reasonable beliefs of Hussman Strategic Advisors. They are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of the prospective returns of any of the Hussman Funds. Actual returns may differ substantially from the estimates provided. Estimates of prospective long-term returns for the S&P 500 reflect our standard valuation methodology, focusing on the relationship between current market prices and earnings, dividends and other fundamentals, adjusted for variability over the economic cycle.