The Speculative “V”

John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

President, Hussman Investment Trust

January 2021

It’s essential to monitor the uniformity of market internals, because investors still have the speculative bit in their teeth. The problem is that this has also often been true at the very peak of ‘V’ tops like 1929 and 1987. That’s why sufficiently overextended conditions can hold us to a neutral stance even in some periods when our measures of market internals are constructive. An increase in divergence or general weakness across individual stocks, industries, sectors, or security-types (including debt securities of varying creditworthiness) would shift market conditions to a combination of extreme valuations and unfavorable internals, and open up the sort of ‘trap door’ situation that we observed in March.

– John P. Hussman Ph.D., December 20, 2020

The speculative “V” is one of the most interesting and challenging features of the market cycle. For passive investors, it can be a period of exhilaration followed by panic. For historically-informed, value-conscious investors, it’s typically a period of annoyance, bordering on contempt, for what Galbraith called “the extreme brevity of the financial memory” – often followed by opportunity and even vindication. Still, the collapse of a speculative bubble can be curiously unsatisfying (as it was for me during the 2000-2002 and 2007-2009 collapses) if one happens to care about the well-being of others.

As I’ve often discussed, the only aspect of the recent speculative bubble that was truly “different” from other market cycles across history was this: even extreme syndromes of “overvalued, overbought, overbullish” market conditions failed to signal a reliable “limit” to speculation. In late-2017, I abandoned my bearish response to those syndromes, along with my belief that reliable “limits” to the recklessness of Wall Street still exist. But as we saw as recently as March, the market can still suffer significant losses during periods of risk-aversion, when the speculative bit drops out of investors’ teeth.

Market cycles haven’t ceased to exist. It’s just that historically reliable “limits” haven’t been effective in recent years. So we’ve become content to gauge the presence of speculation or risk-aversion, without immediately becoming bearish once speculation has become outrageous. While sufficiently extreme conditions can still hold us to a neutral market outlook, the shift to a bearish outlook requires deterioration or divergence in our measures of market internals, which are our most reliable gauge of whether investor psychology is inclined toward speculation or toward risk-aversion.

A week ago, our primary measures of market internals shifted to a negative condition. That shift was a bit surprising, because it was driven by components that capture market behavior across “debt securities of varying creditworthiness.” Interestingly, those debt-sensitive components were also the first to shift negative at the 1987 and 1929 peaks. The equity components shifted later. I often describe unfavorable shifts in market internals as being driven by “deterioration” and “divergence.” In 1987 and 1929, the ascent to the bull market peak was so steep and indiscriminate that there was little “divergence” in the equity components at the highs. Instead, the equity components shifted only after a sharp, near-vertical initial loss.

Even without the negative shift in our measures of market internals last week, we’ve been on high alert. There are only a handful of times when we’ve observed “overvalued, overbought, overbullish” syndromes that were also sufficiently frantic to drive the S&P 500 more than 10% above its 10-week low, and 10% above its 40-week average. That’s the advancing side of a “V,” and while that combination has only sometimes marked a bull market top from a full-cycle perspective, it has never been good from an intermediate-term perspective. This time may be different, but even the instances in the past couple of years have been unfavorable.

These instances cluster into 9 previous episodes across history: August 1929 (precise bull peak), August 1987 (precise bull peak), March 1998 (which was rather uneventful, but still associated with a correction of more than 12% from March levels by late-August), March 2000 (precise bull peak), April 2010 (which was followed by an unmemorable 16% correction into early-July), February 2011 (another unmemorable one, though also followed by a 16% correction by October), January 2018 (followed by a very quick 10% correction), late-August/early-September 2020 (followed by a very quick 10% correction), and today. The final bull market advances that preceded the 1972-74 and 2007-2009 collapses were a bit less steep, so they aren’t included among these episodes.

Though our most reliable measures of market valuations presently exceed levels observed at both the 1929 and 2000 market peaks, there’s no assurance the current “V” – at this point, only the left side of a “V” – is the peak of a cyclical bull market. What I can say with reasonable confidence is that present conditions – a combination of record valuations, “overvalued, overbought, overbullish” conditions, rare overextension, and critically, fresh deterioration in our key gauge of market internals – are permissive of steep and abrupt market losses.

Put simply, the present constellation of market conditions creates the potential for the sort of “trap door” situation we observed in March. Still, an improvement in our measures of market internals would ease this risk, and could even create a constructive opportunity if improved market internals are first preceded by a material retreat in market valuations.

There’s no question that valuations have been extreme for years now. That’s one of the defining features of a bubble: it’s impossible to establish the most obscene valuations in history without repeatedly advancing through lesser extremes. The only choice is to find a good response to a bad situation. In my view, the best response isn’t to capitulate to the idea that ‘this time is different,’ but to instead:

- Recognize that financial bubbles have repeatedly occurred throughout history, and that extending the bubble only serves to magnify its eventual consequences;

- Find some reliable measure to gauge whether investors are inclined toward speculative or risk-averse psychology. For us, the best gauge is the uniformity of market internals, because when investors are inclined to speculate, they tend to be indiscriminate about it;

- Be content with a neutral stance during periods when extreme valuations and overextended conditions are coupled with speculative psychology, be willing to adopt a constructive outlook (with a safety net) if short-term conditions are oversold and your gauges of speculation are still intact, and don’t adopt a bearish stance until market internals or similar gauges indicate growing risk-aversion among investors.

– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., A Good Response to a Bad Situation

The full-cycle and long-term market outlook remains dismal

I continue to expect a loss in the S&P 500 on the order of 65-70% over the completion of the current market cycle. As I noted about my 83% loss projection for tech stocks in March 2000, “if you understand values and market history, you know we’re not joking.” A loss on the order of 65-70% would merely bring the S&P 500 to historical norms that have been followed by historically run-of-the-mill returns.

Still, suppose one believes that U.S. stocks should forever be priced at levels implying long-term returns of roughly 5.5% annually (without ever approaching 9% or even 7%). In that world, stock prices and fundamentals would grow in parallel, but the ratio between prices and fundamentals would have to maintain a “permanently high plateau.” We can’t actually rule that out, but one should also realize that an increase of just 0.5% annually in the long-term return required by investors would still induce a 25% market loss. So even slight variations in permanently extreme valuations and permanently low returns would produce substantial cyclical volatility anyway, and as full-cycle investors, we’d be just fine with that.

Likewise, suppose it takes 20 years for valuations simply to touch levels consistent with future long-term returns of say, 7% annually, and S&P 500 fundamentals grow at the same nominal annual rate as they have since 2000 (including the full benefit of repurchases). The unfortunate arithmetic associated with those assumptions is that the total return of the S&P 500 would likely average just over 2% annually during the coming 20 years.

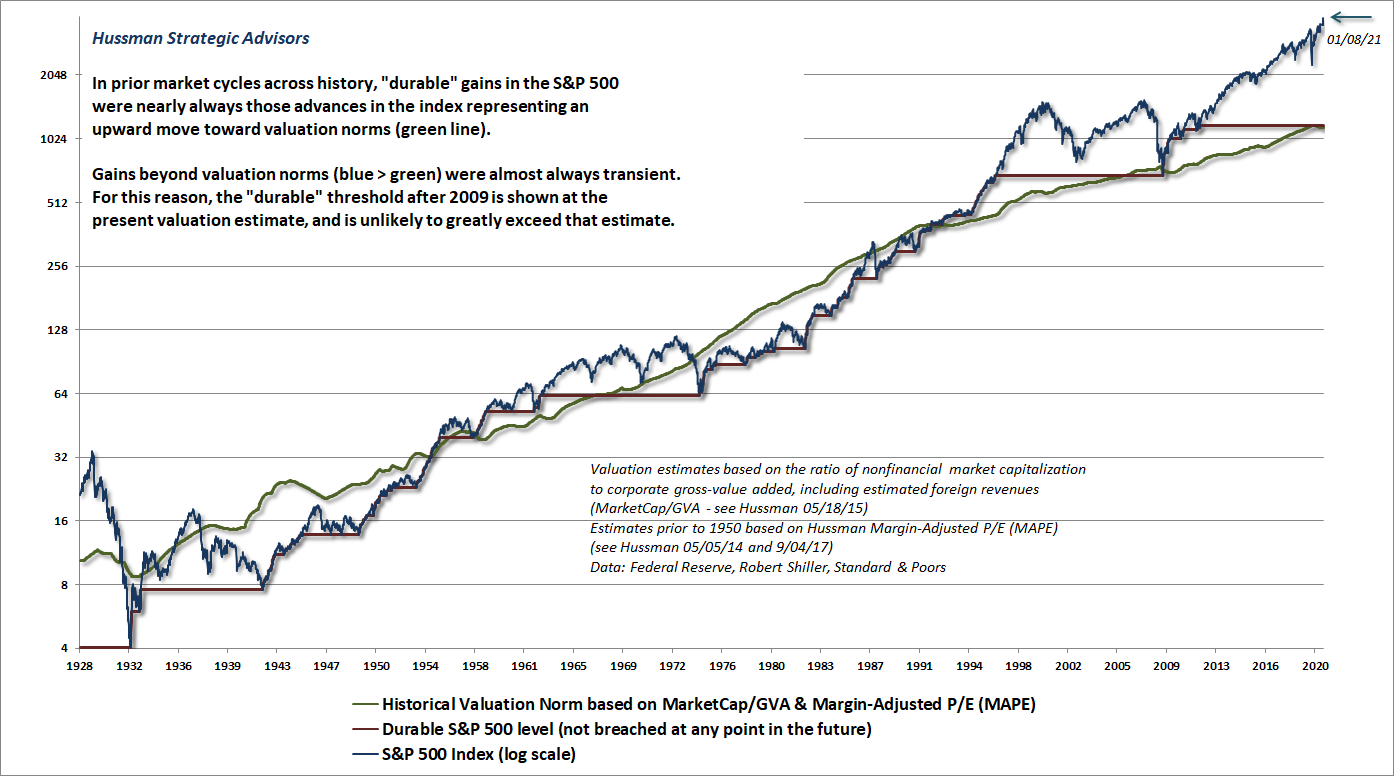

The chart below shows the current position of the market from the standpoint of the most reliable valuation measures we use (based on their correlation with actual subsequent market returns). Note that advances in the S&P 500 (blue line) far beyond reliable valuation norms (green line) tend to be transient. In contrast, advances in the S&P 500 toward valuation norms tend to be durable. The red stairstep marks “durable” levels in the S&P 500 that were never breached in subsequent market cycles. Given that market gains well beyond reliable valuation norms have almost always been transient, the “durable” threshold after 2009 is set at the present valuation estimate, and is unlikely to substantially exceed that estimate.

Advances in the S&P 500 far beyond reliable valuation norms tend to be transient. In contrast, advances in the S&P 500 toward valuation norms tend to be durable.

Also notice that it took two cycles, not just one, to fully dissipate the valuation extremes observed at the 2000 market peak. It’s instructive to observe that the total return of the S&P 500 lagged Treasury bills for the full period from May 1995 to March 2009, despite two intervening bubbles. Such long, interesting trips to nowhere typically result from of elevated starting valuations, depressed ending valuations, or some combination of both. Given current extremes, that’s exactly what I believe passive investors should expect.

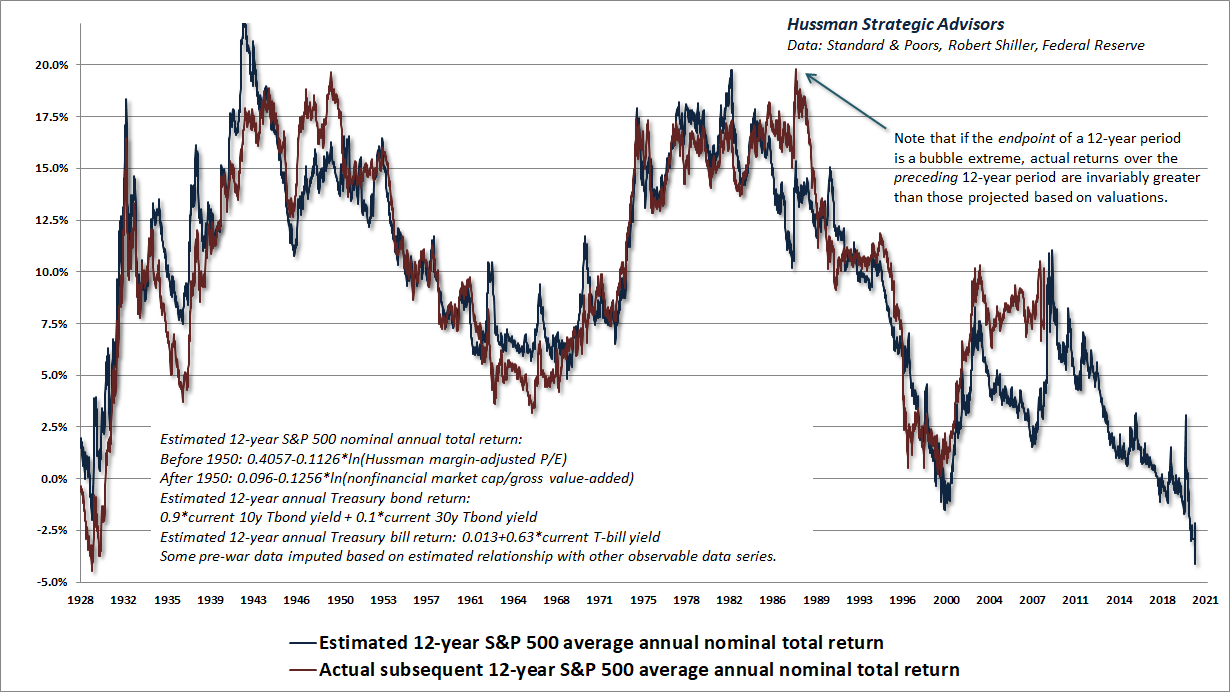

The chart below shows our estimate of 12-year S&P 500 nominal annual total returns. The red line shows the actual subsequent S&P 500 total return from each point in time. Notice that there are a few “errors” in this chart (such as 1988 and 2008). These “errors” occur because the end of the 12-year period is a bubble extreme (such as 2000 and today). So if market valuations 12 years from now are just as extreme as they are today, it’s true that investors will be more likely to have enjoyed 12-year returns in the low positive single digits rather than the low negative single digits. Still, when zero returns are the mid-point between the most likely outcome and the most optimistic one (ruling out pessimistic outcomes altogether), my impression is that investors may have overextended themselves.

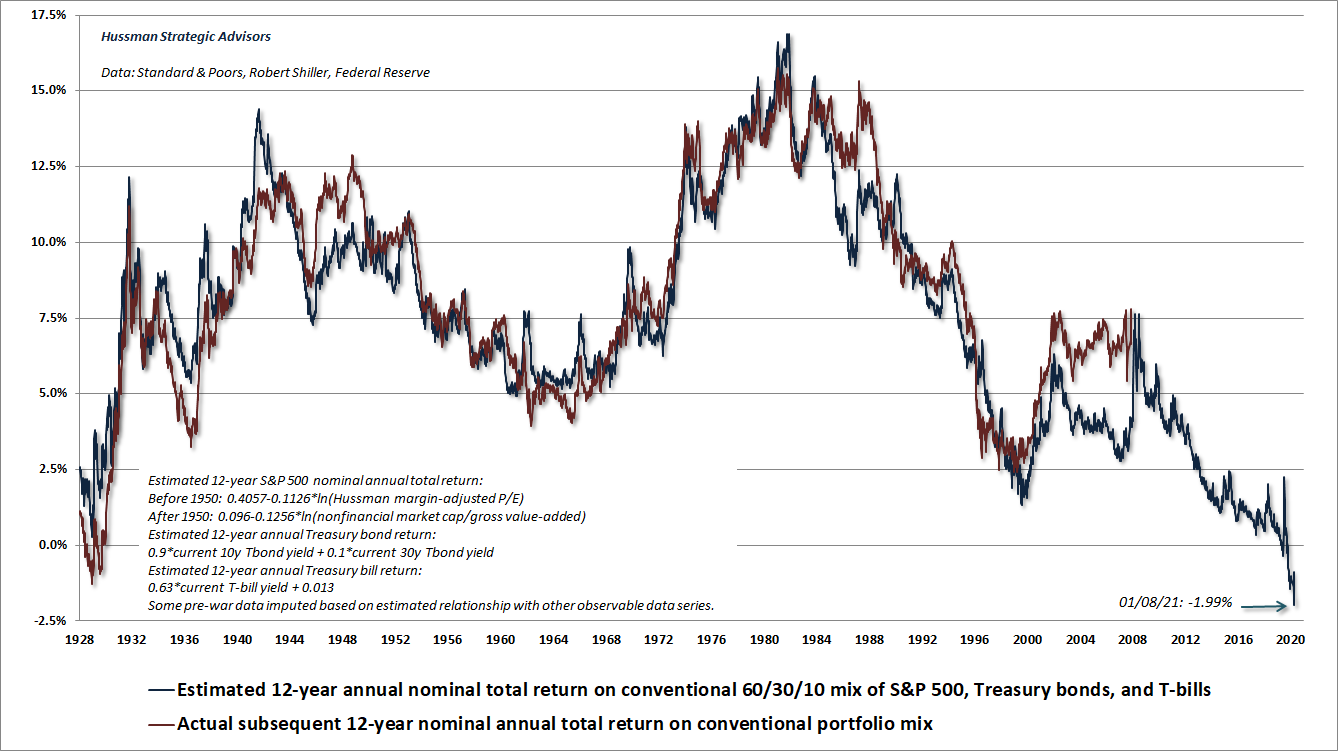

The chart below shows our estimate of expected 12-year nominal total returns for a conventional, passive investment mix invested 60% in the S&P 500, 30% in Treasury bonds, and 10% in Treasury bills. This estimate is presently easily the worst in history.

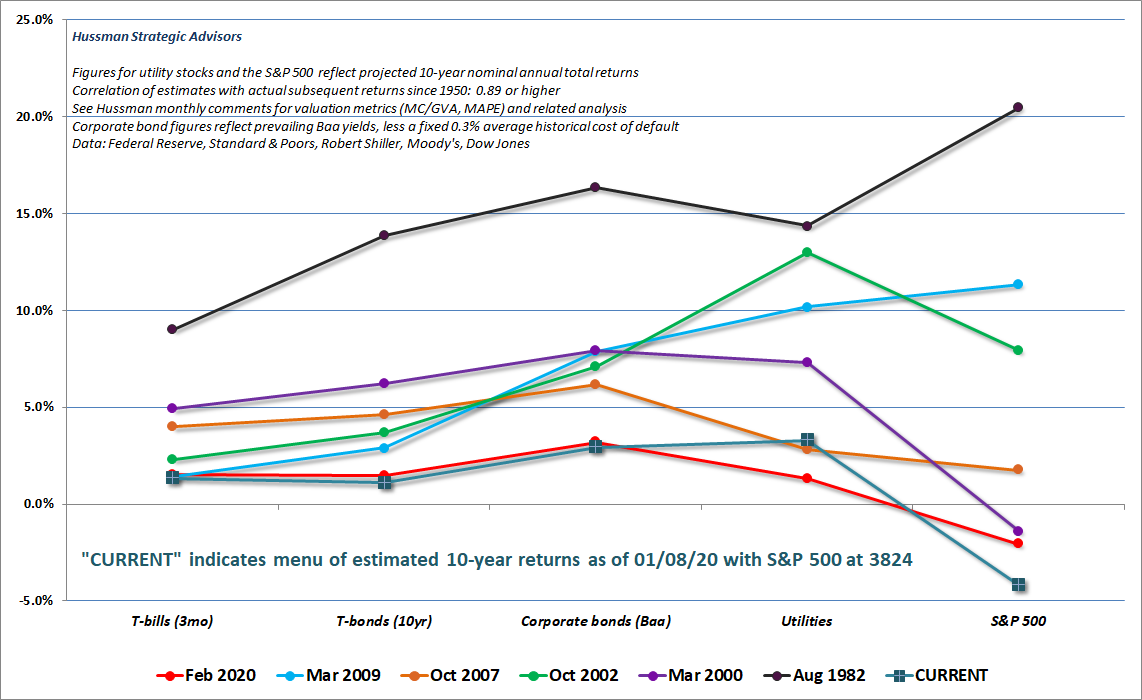

By our estimates (all of which have a correlation of 0.89 or greater with actual subsequent returns in data since 1950), the menu of prospective returns across conventional, passive investment choices is easily the worst on record, with the possible exception of utility stocks, where our projections are marginally better than they were at the February 2020 and October 2007 market highs. The essential thing to understand, however, is that these prospective returns change as valuations do.

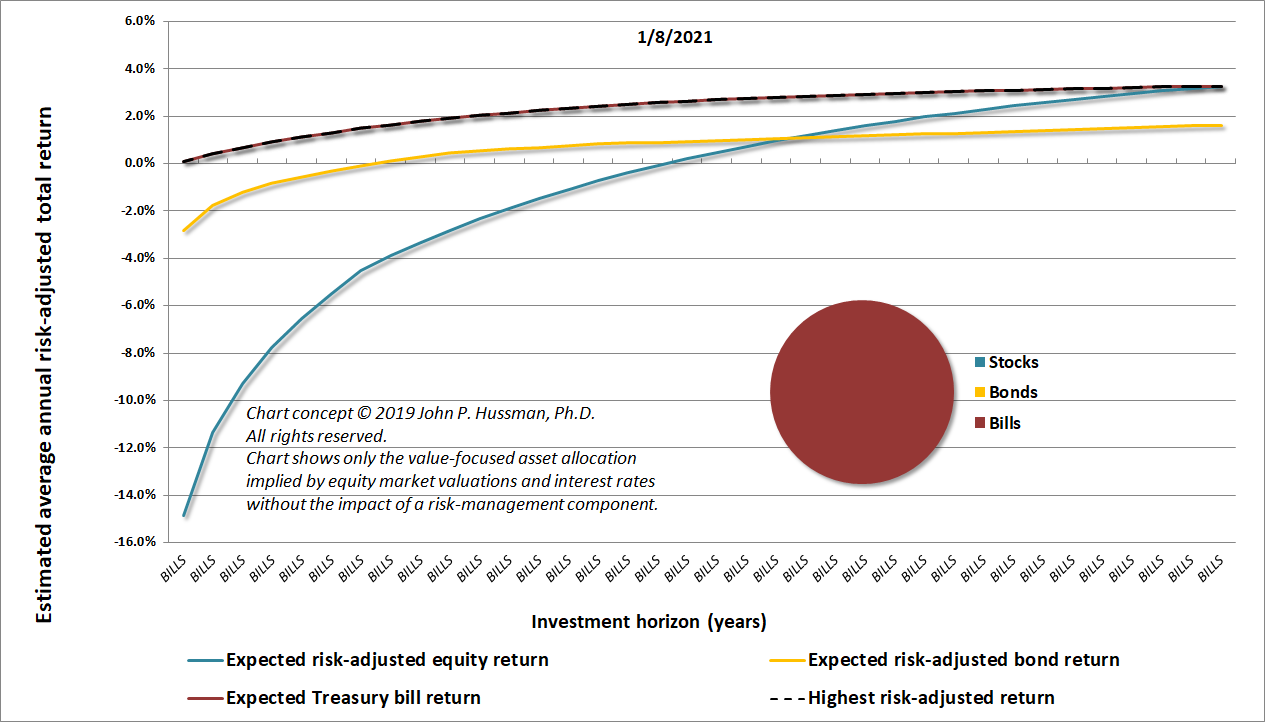

In a 2019 white paper, I detailed an approach to estimate a “value-focused asset allocation” by jointly considering prevailing stock market valuations and interest rates. It specifies an investment allocation based on which asset class is estimated to have the highest average annual expected return, adjusted for risk, to each point in a long-term investment horizon. That allocation can then be modified by a risk-management component, to adjust exposure during segments of the market cycle where risk-aversion or speculation among market participants may temporarily drive valuations to depressed or elevated levels. The white paper includes numerous charts showing how this value-focused asset allocation has changed across market history, particularly at important peaks and troughs in the stock and bond markets.

The chart below shows this value-focused asset allocation based on current interest rates and S&P 500 valuations (not including the impact of risk-management considerations based on market internals, overextended conditions, and other factors). Even assuming that Treasury bill yields don’t rise beyond 3% even 30 years from now, the value-focused allocation presently allocates nothing to stocks. Emphatically, despite interest rates that are near zero, there are only two other times in history that the value-focused allocation was as defensive as it is presently: 1929, and two weeks in April 1930, at the peak of the post-crash advance that preceded a further 84% market loss. In practice, we prefer hedged equity to zero-interest cash, but I do believe that measured from the current valuation extreme, exposure to market risk (“beta”) is likely to be unrewarding, on average, for well over a decade.

This allocation will change as valuations do. A steep market retreat followed by an improvement in market internals could encourage a more constructive outlook. So it’s not a permanent situation, but here and now, zero interest rates do not require investors to lock in the prospect of zero or negative returns for over a decade, along with the additional risk of profound interim losses.

What alternative is there?

As I noted a year ago, I don’t think it’s terribly useful to imagine there’s some passive investment that will help investors solve the problem created by an “everything bubble,” unless it’s a passive investment in an active discipline. Personally, I prefer to follow a value-conscious, historically-informed, full-cycle discipline that responds to evidence as it changes. Indeed, even amid the most extreme valuations in history, our late-2017 adaptations helped us to have reasonable flexibility in our market outlook amid last year’s volatility.

Nothing demands that investors ‘lock in’ the lowest investment prospects in history. The alternative that investors have is flexibility. The alternative investors have is the capacity to imagine a complete market cycle. The alternative investors have is discipline – the willingness to lean away from risk when it is richly valued and unsupported by uniformly favorable internals, and to lean toward risk when a material retreat in valuations is joined by an improvement in the uniformity of market internals. I have every expectation that we’ll observe such opportunities over the completion of this cycle.

– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., January 2020

As for alternative assets such as precious metals, our outlook varies considerably as market conditions change, but I’ve always felt that inflation hedges have a place as part of a well-diversified portfolio. It’s important to recognize that many of these are less well-correlated with inflation, particularly on a year-to-year basis, than investors seem to imagine. In short, inflation hedges can be enormously useful over the complete cycle (even in environments of relatively muted inflation), but they can also be quite volatile. We respond to changes in conditions such as valuation, economic activity, real interest rates, currency movements, and other factors to navigate that volatility.

On the subject of Bitcoin, my rather unpopular view hasn’t changed at all: Blockchain is a remarkable algorithm. Bitcoin is a limited-supply token generated by a replicable, low-bandwidth, wildly energy-inefficient blockchain app, with neither government fiat, physical convertibility, nor reserve requirements to compel its use, or to make it something other than an abstract numeraire. The value of any currency is essentially the discounted stream of services it is expected to provide as a medium of exchange and a store of wealth. That value relies on the willingness of a whole sequence of successive holders to accept the currency. It’s turtles all the way down. Ultimately, the confidence of those successive holders requires some feature – fiat or convertibility – to pin it to the real world, so it’s not entirely self-referential.

Thus far, the main use of these tokens outside of speculation seems to be for the purpose of exchanging the tokens themselves (which smacks of money laundering). The psychological value of these tokens seems to be largely based on the backward-looking sunk-cost of the energy wasted to “mine” them, by producing a validation hash (as “proof of work”) for a given block of transactions. Whoever produces that hash first gets paid. Everyone else’s computational “work” is completely wasted. It’s rather tragic from an environmental perspective, and I wouldn’t be terribly surprised if Bitcoin was actually a brainchild of the energy industry. There’s also a subtle Ponzi-like aspect in that once you own Bitcoin, you’ve got to participate in a future transaction block to get out, regardless of how much that future block costs to validate.

Still, even if a bubble is entirely self-referential, it doesn’t mean people who get in early can’t also obtain a transfer of wealth from some subsequent speculator before the bubble collapses. It’s just that everyone assumes it will be someone else. Give people a limited-supply object coupled with a speculative mindset, and Dutch tulips gonna Dutch tulip. I also hear that on the Neopets app, paintbrushes and unconverted Neopets are selling for over a million NeoPoints.

Monetary, fiscal policy, and “money flow”

What actually happens when the Federal Reserve “expands its balance sheet” and “pumps money into the economy”? [I visibly cringed as I typed that]. It means that the Fed has purchased a bond from the public and has paid for it by creating a different government liability. In most cases, these liabilities aren’t currency, but bank reserves in the account of whoever sold the bond. Together, currency and bank reserves are what we call the “monetary base.”

In a nutshell, monetary easing replaces interest-bearing Treasury bonds that were previously held by the public, with zero-interest hot potatoes that someone in the economy must hold, at every moment in time, as zero-interest base money, until it is retired. Now, monetary policy can certainly be useful when there’s a run on bank liquidity, and depositors become frantic to convert their bank deposits into currency. But taken to excess, these policies are also how speculative bubbles are encouraged – by creating a pile of zero-interest hot potatoes that are so psychologically uncomfortable to hold that people become willing to pay any price in order to get hold of some other investment asset.

The trouble is that investment assets like stocks are just claims on some future stream of cash flows that will be delivered over time. The higher the price you pay for those future cash flows, the lower the long-term return you can expect on your investment, as those cash flows are delivered. Pay $100 today for a $100 payment a decade from today, and you can expect a very long – though possibly interesting – trip to nowhere. Pay more than $100 today for that same cash flow, and you can expect a negative long-term return. That’s exactly what we estimate that investors are bargaining for over the coming 10-12 years in the S&P 500.

In aggregate, cash never comes “off the sidelines” because there are no “sidelines.” Every security that is issued, whether it’s a stock share, or a bond certificate, or a dollar of base money, has to be held by someone, at every moment in time, exactly in the form it was issued, until it is retired. The only thing that changes is who holds what, and how much of one security investors are willing to exchange for another.

The Federal Reserve’s policies of quantitative easing and zero interest rates simply create a mountain of zero-interest hot potatoes that someone must hold at every moment in time, until they are retired. It’s important to realize that the monetary base doesn’t “go” anywhere. It remains base money until it is retired. You can try to get rid of base money by putting it “into” the stock market. But the moment the transaction takes place, the base money goes right back “out of” the stock market in the hands of whoever sold the stock.

In aggregate, cash never comes “off the sidelines” because there are no “sidelines.” Every security that is issued, whether it’s a stock share, or a bond certificate, or a dollar of base money, has to be held by someone, at every moment in time, exactly in the form it was issued, until it is retired. The only thing that changes is who holds what, and how much of one security investors are willing to exchange for another. The base money created by the Fed doesn’t go “into” the stock market. It just encourages so much discomfort with those hot potatoes that investors become willing to bid stock prices up to valuations that imply long-term returns near zero, or worse. You can only sustain that sort of distortion by making its consequences worse.

As for fiscal policy, I’m very much in favor of well-structured spending policies to address the current pandemic, and I’ve detailed some of those views in prior comments. I’m hopeful that some of it will be reflected in coming legislation. I’m not at all in favor of the Federal Reserve administering these programs, however, and believe it is ill-equipped to do so. You can find a lot of this discussion in my 2020 comments, so I won’t repeat those economic policy considerations here.

One of the aspects of fiscal policy that’s worth discussing from an investment standpoint is the potential effect of deficit spending on the stock market. Currently, part of the bubble thesis is that deficit spending will somehow “find its way into stocks.” As much as I hope that new legislation will benefit general economic activity, it’s actually impossible, in aggregate, for the fiscal deficits to “go into” the stock market.

The reason is that a deficit in the government sector must be matched by a surplus in some other sector of the economy. But that deficit must also be financed. Every government deficit is accompanied by the novel creation of additional Treasury securities (or if the Fed buys them, additional base money). Those new government liabilities, in equilibrium, must be held by somebody. Ultimately, the additional private “surplus” generated by government deficit spending must, in aggregate, be invested in the new government liabilities that financed it. The surplus can’t “go into” stocks – not only because money never goes “into” or “out of” a secondary market, but also because in aggregate, taking the economy as a whole, the newly created surplus must be held in the form of the newly issued government liabilities.

That was a lot for one paragraph, so let’s break things down. We’ll start with an accounting identity: If one sector of the economy runs a “deficit,” where its consumption and net investment is greater than its income, you can be absolutely sure that some other sector of the economy will run a “surplus” in which the income of that sector will exceed its consumption and net investment. In an open economy, that “surplus” may accrue to foreign countries.

Here’s some arithmetic that may help to conceptualize how the deficit of one sector emerges as the surplus of another.

Government consumption expenditures, net investment, and transfer payments – Government tax revenue = Household after-tax income not spent on consumption or real net household investment + Undistributed after-tax corporate profits not used for real net corporate investment + Foreign income due to the U.S. trade deficit (i.e. imports – exports)

An example may be useful. Suppose Decker takes a fallen tree from his yard, crafts it into a patio deck, and that the new deck is the only production that takes place in town that day. Sam wants to buy the deck, but needs to borrow the money, so Sam writes an IOU to his niece, Sally, in return for a $100 bill that Sam gives to Decker. So Uncle Sam runs a $100 “deficit” of consumption and net investment over and above his income. That deficit is matched by Decker’s $100 “surplus” of income not spent on consumption or net investment. There’s a new $100 IOU created, and in equilibrium, someone in the economy must end up owning that IOU. In this case, it’s Sally.

Decker can certainly take his newly earned $100 bill and buy a few shares of stock from Charlie, but all that happens there is that Charlie ends up with the $100 bill, and Decker ends up with the shares that were previously owned by Charlie. Does that “money flow” cause stock prices to go up or down? That depends on who was more eager – Decker to buy, or Charlie to sell. It’s that balance of psychology that drives prices, not the so-called “money flow.”

When all is said and done, the deficit of Uncle Sam gives rise to an equivalent surplus (of income in excess of consumption and net investment) somewhere else in the economy. Likewise, that surplus must, in equilibrium, be held by somebody in the economy, in the form of the newly issued security that financed the deficit.

On the “wealth” of a nation

Somehow, policy makers have come to imagine that the paper value of securities is equivalent to prosperity. It’s a fallacy that has been repeated across economic history, and it always ends badly. We can certainly hope that government support helps the economy in other ways that will benefit households, employment, and productive investment. It had better, because prosperity is created in the real side of the economy, not the financial side. Wealth is not created by fluctuations in the price of securities, but by value-added production: the creation of output that has greater value to society than the inputs used to produce it.

See, securities are not net economic wealth. Every security is both an asset to the holder and a liability to the issuer. It is a claim of one party in the economy – by virtue of past saving – on the future output produced by others.

If one carefully accounts for what is spent, what is saved, and what form those savings take (securities that transfer the savings to others, or tangible real investment of output that is not consumed), one obtains a set of “stock-flow consistent” accounting identities that must be true at each point in time:

- Total real saving in the economy must equal total real investment in the economy;

- For every investor who calls some security an “asset” there is an issuer that calls that same security a “liability”;

- The net acquisition of all securities in the economy is always precisely zero, even though the gross issuance of securities can be many times the amount of underlying saving; and perhaps most importantly,

- When one nets out all the assets and liabilities in the economy, the only thing that is left – the true basis of a society’s net worth – is the stock of real investment that it has accumulated as a result of prior saving, and its unused endowment of resources. Everything else cancels out because every security represents an asset of the holder and a liability of the issuer.

Conceptualizing “saved or unconsumed resources” as broadly as possible, the wealth of a nation consists of its stock of real private investment (e.g. housing, capital goods, factories), real public investment (e.g. infrastructure), intangible intellectual capital (e.g. education, inventions, organizational knowledge and systems), and its endowment of basic resources such as land, energy, and water. In an open economy, one would include the net claims on foreigners (negative, in the U.S. case). These should be the central objects of policies that target our long-term prosperity.

A hypervalued stock market doesn’t create wealth. At best, it only provides the holders of stocks the temporary opportunity to obtain a transfer of wealth, by selling those stocks to some other poor soul who will suffer the dismal long-term returns and steep interim losses instead.

If we want a stronger economy and a brighter future, there will come a point where we will need to abandon the delusion that overvalued securities are aggregate wealth. They are not. Aggregate wealth is not created by jacking up security prices, but by increasing the ability of the economy to generate useful, value-added economic output and deliverable long-term cash flows. There will come a point where we will have to recognize that a speculative bubble can only be extended by making its consequences worse.

In Honor and Remembrance of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.

– Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. King was a friend of my dear teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh. Though Dr. King was a Christian minister, and Thay (“teacher”) is a Buddhist monk, one of the convictions they shared was that we are more than our separate selves. Enlightenment, to a Buddhist, isn’t some “achievement” to be attained. I think all of us experience it at least briefly, in those moments when we become so mindful of our interconnection – that all of us are just waves composed from the same water – that ideas like equality, justice, and compassion become simple and unquestionable. As a minister, Dr. King said, “you come to the point that you look in the face of every man and see deep down within him what religion calls ‘the image of God,’ you begin to love him in spite of. No matter what he does, you see God’s image there. There is an element of goodness that he can never slough off.” To see that, is enlightenment.

Meister Eckhart put it this way – “All creatures are interdependent. Every creature is a word of God.” Consider then, for a moment, that of the nearly 6 million children under the age of 5 who die every year globally, half of them are black; that maternal mortality in Africa is ten times that in the Americas, and more than three times that of any other region reported by the World Health Organization; that the number of black children under the age of 5 in the U.S. represent fewer than one-third the number of white children, yet the number of fatalities among these children are over half those of white children.

There are a hundred statistics one could quote that have the same basic structure. It shouldn’t be a subject of offense to say “Black lives matter” – to insist that they matter – in a world where other lives have always mattered; have always enjoyed the privileges of economic opportunity, freedom, voting rights, decent health systems; strong educational systems, and the benefit of the doubt, in nearly every circumstance. At it’s core, it’s a statement about our shared humanity.

For some, the immediate response to the words “Black lives matter” is to counter by saying “All lives matter,” as if those additional lives are not already blessed by a world that advantages them. There’s no argument, of course, that all lives matter – it’s just that some of them have always mattered, while others somehow still face a world that needs to be reminded.

Somehow, this assertion has been disfigured, as if it’s equivalent to supporting a riot (even though the vast majority of BLM protesters last summer were peaceful). Dr. King was very clear on points like this, condemning violence unequivocally (context that should not be removed from his words). Yet he also saw the need for analysis, and for remedies. Those remedies may be a useful way to distinguish between principled protest and disgraceful protest (apart from the number of Tiki torches and Viking helmets involved). Principled protest seeks solutions like “justice, equality, and humanity.” Disgraceful protest seeks unjust outcomes and dishonorable concessions.

Certain conditions continue to exist in our society, which must be condemned as vigorously as we condemn riots. But in the final analysis, a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity. And so in a real sense our nation’s summers of riots are caused by our nation’s winters of delay.

– Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

All of this may strike some as “too political.” But it would be an injustice to celebrate Dr. King without addressing the vision for which he fought hardest. That vision wasn’t to have his words “I have a dream” tossed around like a motivational message from a cat poster (as one recently re-elected Senate leader chose to quote him). It was to realize a world where not only some lives, but all lives actually do matter. To say “Black lives matter” isn’t an attempt to exclude the importance of other lives. It’s an affirmation that Black lives – and more broadly, people of color – deserve equal standing with those that our nation values so plainly that many of us simply take the privilege for granted.

Though it’s a larger conversation, it’s also worth considering the way that our existing economic structures operate to amplify disparities. These disparities exist across the board, but fall hardest on people of color. Just 1% of Americans own 31% of U.S. private net worth. The next 9% owns an additional 38%. The share of the next 40% (between the 90th and 50th percentile) has collapsed over the past 30 years, to 29%, while the lowest 50% hold just 2% of net worth, and the increase from just 0.4% since the global financial crisis is hailed as some sort of victory.

While effort and innovation are essential to wealth creation, disparities of this magnitude are not simply a reflection of relative effort or personal merit. They are a reflection of amplifiers, network effects and feedback loops. Few engines have been more effective at that than fiscal and monetary policies (mainly tax structure and Federal Reserve interventions) that disfigure the word “capital.” Financial capital – corporate securities, profits, investment gains, and the funneled benefits of natural monopolies, are all treated as sacrosanct. They enjoy wildly preferential treatment compared with wage income, with little concern – or at best, trickle-down concern – for productive capital (real investment, infrastructure, education), or the resulting distribution of economic benefits. We need to do better, and we should welcome change.

True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to recognize that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.

– Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. King noted that he tried to speak on the subject below at least once a year. Preserving that tradition has always seemed an appropriate way to honor him. If you’ve never read Dr. King’s writings, this talk is a good place to start. I don’t think it’s possible to read his words without coming away better for it.

Loving Your Enemies

November 17 1957

“I want to use as a subject from which to preach this morning a very familiar subject, and it is familiar to you because I have preached from this subject twice before to my knowing in this pulpit. I try to make it a, something of a custom or tradition to preach from this passage of Scripture at least once a year, adding new insights that I develop along the way out of new experiences as I give these messages. Although the content is, the basic content is the same, new insights and new experiences naturally make for new illustrations.

“So I want to turn your attention to this subject: “Loving Your Enemies.” It’s so basic to me because it is a part of my basic philosophical and theological orientation – the whole idea of love, the whole philosophy of love. In the fifth chapter of the gospel as recorded by Saint Matthew, we read these very arresting words flowing from the lips of our Lord and Master: “Ye have heard that it has been said, ‘Thou shall love thy neighbor, and hate thine enemy.’ But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them that despitefully use you; that ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven.”

“Over the centuries, many persons have argued that this is an extremely difficult command. Many would go so far as to say that it just isn’t possible to move out into the actual practice of this glorious command. But far from being an impractical idealist, Jesus has become the practical realist. The words of this text glitter in our eyes with a new urgency. Far from being the pious injunction of a utopian dreamer, this command is an absolute necessity for the survival of our civilization. Yes, it is love that will save our world and our civilization, love even for enemies.

“Now let me hasten to say that Jesus was very serious when he gave this command; he wasn’t playing. He realized that it’s hard to love your enemies. He realized that it’s difficult to love those persons who seek to defeat you, those persons who say evil things about you. He realized that it was painfully hard, pressingly hard. But he wasn’t playing. We have the Christian and moral responsibility to seek to discover the meaning of these words, and to discover how we can live out this command, and why we should live by this command.

So this morning, as I look into your eyes, and into the eyes of all of my brothers in Alabama and all over America and over the world, I say to you, ‘I love you. I would rather die than hate you.’ And I’m foolish enough to believe that through the power of this love somewhere, men of the most recalcitrant bent will be transformed.

– Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Now first let us deal with this question, which is the practical question: How do you go about loving your enemies? I think the first thing is this: In order to love your enemies, you must begin by analyzing self. And I’m sure that seems strange to you, that I start out telling you this morning that you love your enemies by beginning with a look at self. It seems to me that that is the first and foremost way to come to an adequate discovery to the how of this situation.

“Now, I’m aware of the fact that some people will not like you, not because of something you have done to them, but they just won’t like you. But after looking at these things and admitting these things, we must face the fact that an individual might dislike us because of something that we’ve done deep down in the past, some personality attribute that we possess, something that we’ve done deep down in the past and we’ve forgotten about it; but it was that something that aroused the hate response within the individual. That is why I say, begin with yourself. There might be something within you that arouses the tragic hate response in the other individual.

“This is true in our international struggle. Democracy is the greatest form of government to my mind that man has ever conceived, but the weakness is that we have never touched it. We must face the fact that the rhythmic beat of the deep rumblings of discontent from Asia and Africa is at bottom a revolt against the imperialism and colonialism perpetuated by Western civilization all these many years.

“And this is what Jesus means when he said: “How is it that you can see the mote in your brother’s eye and not see the beam in your own eye?” And this is one of the tragedies of human nature. So we begin to love our enemies and love those persons that hate us whether in collective life or individual life by looking at ourselves.

“A second thing that an individual must do in seeking to love his enemy is to discover the element of good in his enemy, and every time you begin to hate that person and think of hating that person, realize that there is some good there and look at those good points which will over-balance the bad points.

“Somehow the “isness” of our present nature is out of harmony with the eternal “oughtness” that forever confronts us. And this simply means this: That within the best of us, there is some evil, and within the worst of us, there is some good. When we come to see this, we take a different attitude toward individuals. The person who hates you most has some good in him; even the nation that hates you most has some good in it; even the race that hates you most has some good in it. And when you come to the point that you look in the face of every man and see deep down within him what religion calls “the image of God,” you begin to love him in spite of. No matter what he does, you see God’s image there. There is an element of goodness that he can never slough off. Discover the element of good in your enemy. And as you seek to hate him, find the center of goodness and place your attention there and you will take a new attitude.

“Another way that you love your enemy is this: When the opportunity presents itself for you to defeat your enemy, that is the time which you must not do it. There will come a time, in many instances, when the person who hates you most, the person who has misused you most, the person who has gossiped about you most, the person who has spread false rumors about you most, there will come a time when you will have an opportunity to defeat that person. It might be in terms of a recommendation for a job; it might be in terms of helping that person to make some move in life. That’s the time you must do it. That is the meaning of love. In the final analysis, love is not this sentimental something that we talk about. It’s not merely an emotional something. Love is creative, understanding goodwill for all men. It is the refusal to defeat any individual. When you rise to the level of love, of its great beauty and power, you seek only to defeat evil systems. Individuals who happen to be caught up in that system, you love, but you seek to defeat the system.

Within the best of us, there is some evil, and within the worst of us, there is some good. The person who hates you most has some good in him; even the nation that hates you most has some good in it; even the race that hates you most has some good in it… No matter what he does, you see God’s image there. There is an element of goodness that he can never slough off.

“The Greek language, as I’ve said so often before, is very powerful at this point. It comes to our aid beautifully in giving us the real meaning and depth of the whole philosophy of love. And I think it is quite apropos at this point, for you see the Greek language has three words for love, interestingly enough. It talks about love as eros. That’s one word for love. Eros is a sort of, aesthetic love. Plato talks about it a great deal in his dialogues, a sort of yearning of the soul for the realm of the gods. And it’s come to us to be a sort of romantic love, though it’s a beautiful love. Everybody has experienced eros in all of its beauty when you find some individual that is attractive to you and that you pour out all of your like and your love on that individual. That is eros, you see, and it’s a powerful, beautiful love that is given to us through all of the beauty of literature; we read about it.

“Then the Greek language talks about philia, and that’s another type of love that’s also beautiful. It is a sort of intimate affection between personal friends. And this is the type of love that you have for those persons that you’re friendly with, your intimate friends, or people that you call on the telephone and you go by to have dinner with, and your roommate in college and that type of thing. It’s a sort of reciprocal love. On this level, you like a person because that person likes you. You love on this level, because you are loved. You love on this level, because there’s something about the person you love that is likeable to you. This too is a beautiful love. You can communicate with a person; you have certain things in common; you like to do things together. This is philia.

“The Greek language comes out with another word for love. It is the word agape. And agape is more than eros; agape is more than philia; agape is something of the understanding, creative, redemptive goodwill for all men. It is a love that seeks nothing in return. It is an overflowing love; it’s what theologians would call the love of God working in the lives of men. And when you rise to love on this level, you begin to love men, not because they are likeable, but because God loves them. You look at every man, and you love him because you know God loves him. And he might be the worst person you’ve ever seen.

“And this is what Jesus means, I think, in this very passage when he says, “Love your enemy.” And it’s significant that he does not say, “Like your enemy.” Like is a sentimental something, an affectionate something. There are a lot of people that I find it difficult to like. I don’t like what they do to me. I don’t like what they say about me and other people. I don’t like their attitudes. I don’t like some of the things they’re doing. I don’t like them. But Jesus says love them. And love is greater than like. Love is understanding, redemptive goodwill for all men, so that you love everybody, because God loves them. You refuse to do anything that will defeat an individual, because you have agape in your soul. And here you come to the point that you love the individual who does the evil deed, while hating the deed that the person does. This is what Jesus means when he says, “Love your enemy.” This is the way to do it. When the opportunity presents itself when you can defeat your enemy, you must not do it.

“Now for the few moments left, let us move from the practical how to the theoretical why. It’s not only necessary to know how to go about loving your enemies, but also to go down into the question of why we should love our enemies. I think the first reason that we should love our enemies, and I think this was at the very center of Jesus’ thinking, is this: that hate for hate only intensifies the existence of hate and evil in the universe. If I hit you and you hit me and I hit you back and you hit me back and go on, you see, that goes on ad infinitum. It just never ends. Somewhere somebody must have a little sense, and that’s the strong person. The strong person is the person who can cut off the chain of hate, the chain of evil. And that is the tragedy of hate – that it doesn’t cut it off. It only intensifies the existence of hate and evil in the universe. Somebody must have religion enough and morality enough to cut it off and inject within the very structure of the universe that strong and powerful element of love.

“I think I mentioned before that sometime ago my brother and I were driving one evening to Chattanooga, Tennessee, from Atlanta. He was driving the car. And for some reason the drivers were very discourteous that night. They didn’t dim their lights; hardly any driver that passed by dimmed his lights. And I remember very vividly, my brother A. D. looked over and in a tone of anger said: “I know what I’m going to do. The next car that comes along here and refuses to dim the lights, I’m going to fail to dim mine and pour them on in all of their power.” And I looked at him right quick and said: “Oh no, don’t do that. There’d be too much light on this highway, and it will end up in mutual destruction for all. Somebody got to have some sense on this highway.”

“Somebody must have sense enough to dim the lights, and that is the trouble, isn’t it? That as all of the civilizations of the world move up the highway of history, so many civilizations, having looked at other civilizations that refused to dim the lights, and they decided to refuse to dim theirs. And Toynbee tells that out of the twenty-two civilizations that have risen up, all but about seven have found themselves in the junk heap of destruction. It is because civilizations fail to have sense enough to dim the lights. And if somebody doesn’t have sense enough to turn on the dim and beautiful and powerful lights of love in this world, the whole of our civilization will be plunged into the abyss of destruction. And we will all end up destroyed because nobody had any sense on the highway of history.

The strong person is the person who can cut off the chain of hate, the chain of evil. And that is the tragedy of hate – that it doesn’t cut it off. It only intensifies the existence of hate and evil in the universe. Somebody must have religion enough and morality enough to cut it off and inject within the very structure of the universe that strong and powerful element of love.

“Somewhere somebody must have some sense. Men must see that force begets force, hate begets hate, toughness begets toughness. And it is all a descending spiral, ultimately ending in destruction for all and everybody. Somebody must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate and the chain of evil in the universe. And you do that by love.

“There’s another reason why you should love your enemies, and that is because hate distorts the personality of the hater. We usually think of what hate does for the individual hated or the individuals hated or the groups hated. But it is even more tragic, it is even more ruinous and injurious to the individual who hates. You just begin hating somebody, and you will begin to do irrational things. You can’t see straight when you hate. You can’t walk straight when you hate. You can’t stand upright. Your vision is distorted. There is nothing more tragic than to see an individual whose heart is filled with hate. He comes to the point that he becomes a pathological case. For the person who hates, you can stand up and see a person and that person can be beautiful, and you will call them ugly. For the person who hates, the beautiful becomes ugly and the ugly becomes beautiful. For the person who hates, the good becomes bad and the bad becomes good. For the person who hates, the true becomes false and the false becomes true. That’s what hate does. You can’t see right. The symbol of objectivity is lost. Hate destroys the very structure of the personality of the hater.

“The way to be integrated with yourself is be sure that you meet every situation of life with an abounding love. Never hate, because it ends up in tragic, neurotic responses. Psychologists and psychiatrists are telling us today that the more we hate, the more we develop guilt feelings and we begin to subconsciously repress or consciously suppress certain emotions, and they all stack up in our subconscious selves and make for tragic, neurotic responses. And may this not be the neuroses of many individuals as they confront life that that is an element of hate there. And modern psychology is calling on us now to love. But long before modern psychology came into being, the world’s greatest psychologist who walked around the hills of Galilee told us to love. He looked at men and said: “Love your enemies; don’t hate anybody.” It’s not enough – to love your friends – because when you start hating anybody, it destroys the very center of your creative response to life and the universe; so love everybody. Hate at any point is a cancer that gnaws away at the very vital center of your life and your existence. It is like eroding acid that eats away the best and the objective center of your life. So Jesus says love, because hate destroys the hater as well as the hated.

“Now there is a final reason I think that Jesus says, “Love your enemies.” It is this: that love has within it a redemptive power. And there is a power there that eventually transforms individuals. That’s why Jesus says, “Love your enemies.” Because if you hate your enemies, you have no way to redeem and to transform your enemies. But if you love your enemies, you will discover that at the very root of love is the power of redemption. You just keep loving people and keep loving them, even though they’re mistreating you. Here’s the person who is a neighbor, and this person is doing something wrong to you and all of that. Just keep being friendly to that person. Keep loving them. Don’t do anything to embarrass them. Just keep loving them, and they can’t stand it too long. Oh, they react in many ways in the beginning. They react with bitterness because they’re mad because you love them like that. They react with guilt feelings, and sometimes they’ll hate you a little more at that transition period, but just keep loving them. And by the power of your love they will break down under the load. That’s love, you see. It is redemptive, and this is why Jesus says love. There’s something about love that builds up and is creative. There is something about hate that tears down and is destructive. So love your enemies.

“There is a power in love that our world has not discovered yet. Jesus discovered it centuries ago. Mahatma Gandhi of India discovered it a few years ago, but most men and most women never discover it. For they believe in hitting for hitting; they believe in an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth; they believe in hating for hating; but Jesus comes to us and says, “This isn’t the way.”

“As we look out across the years and across the generations, let us develop and move right here. We must discover the power of love, the power, the redemptive power of love. And when we discover that we will be able to make of this old world a new world. We will be able to make men better. Love is the only way. Jesus discovered that.

“And our civilization must discover that. Individuals must discover that as they deal with other individuals. There is a little tree planted on a little hill and on that tree hangs the most influential character that ever came in this world. But never feel that that tree is a meaningless drama that took place on the stages of history. Oh no, it is a telescope through which we look out into the long vista of eternity, and see the love of God breaking forth into time. It is an eternal reminder to a power-drunk generation that love is the only way. It is an eternal reminder to a generation depending on nuclear and atomic energy, a generation depending on physical violence, that love is the only creative, redemptive, transforming power in the universe.

“So this morning, as I look into your eyes, and into the eyes of all of my brothers in Alabama and all over America and over the world, I say to you, “I love you. I would rather die than hate you.” And I’m foolish enough to believe that through the power of this love somewhere, men of the most recalcitrant bent will be transformed. And then we will be in God’s kingdom.”

Keep Me Informed

Please enter your email address to be notified of new content, including market commentary and special updates.

Thank you for your interest in the Hussman Funds.

100% Spam-free. No list sharing. No solicitations. Opt-out anytime with one click.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive news and commentary, at no cost, from Hussman Strategic Advisors, News & Commentary, Cincinnati OH, 45246. https://www.hussmanfunds.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact.

The foregoing comments represent the general investment analysis and economic views of the Advisor, and are provided solely for the purpose of information, instruction and discourse.

Prospectuses for the Hussman Strategic Growth Fund, the Hussman Strategic Total Return Fund, the Hussman Strategic International Fund, and the Hussman Strategic Allocation Fund, as well as Fund reports and other information, are available by clicking “The Funds” menu button from any page of this website.

Estimates of prospective return and risk for equities, bonds, and other financial markets are forward-looking statements based the analysis and reasonable beliefs of Hussman Strategic Advisors. They are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of the prospective returns of any of the Hussman Funds. Actual returns may differ substantially from the estimates provided. Estimates of prospective long-term returns for the S&P 500 reflect our standard valuation methodology, focusing on the relationship between current market prices and earnings, dividends and other fundamentals, adjusted for variability over the economic cycle.