The Government Deficits Land in the Deepest Pockets

John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

President, Hussman Investment Trust

February 2025

Should you change your investment position here? We haven’t. Whether or not we’re at a market peak, we were already defensive based on extreme valuations, unfavorable internals, and overextended conditions. If you’re a passive investor, my intent is not to encourage you to abandon your discipline. What I do believe, however, is that this is an extraordinarily good moment to examine your risk exposures and to take them seriously. If your notion of passive investing doesn’t allow for a realistic possibility of a market loss well in excess of 50%, or a decade or more in which the S&P 500 lags Treasury bills, you’ve not only decided to be a passive investor, you’ve decided to ignore history. So, whatever your discipline, examine your risk exposures.

It’s helpful to keep in mind that anytime you change part of your investment position, there will be regret. If you sell part of your holdings, and the market continues to advance, you’ll regret having sold anything. If you sell part of your holdings and the market declines, you’ll regret not having sold more. The same is true for purchases. There will always be regret. The key is to realize this up front, and choose an acceptable level of regret. You do that by examining your exposure to risk, considering both potential returns and potential losses. That’s my main hope in writing this comment.

– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., You Can Ring My Bell, June 23, 2024

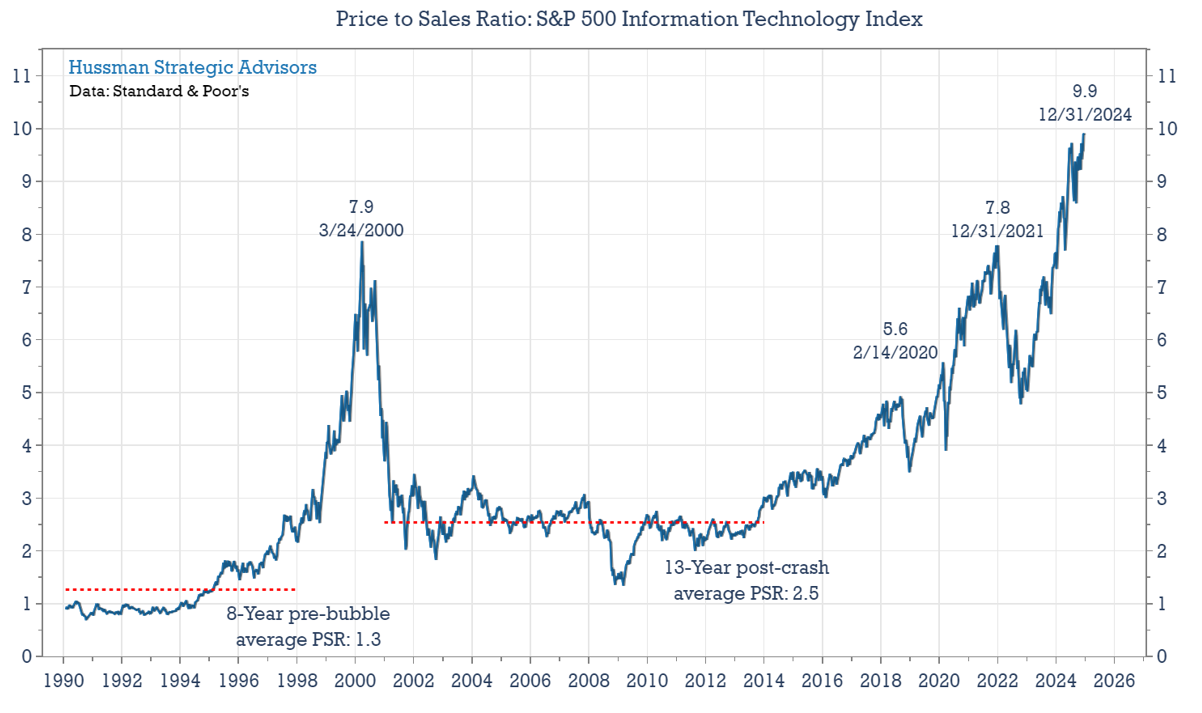

With our most reliable valuation measures more extreme than both the 1929 and 2000 market peaks, we continue to believe that the stock market is tracing out the extended peak of the third great speculative bubble in U.S. history. Since the initial January 2022 market peak, the equal-weighted S&P 500 has clocked a cumulative total return less than 2.4% ahead of Treasury bills, while the small-cap Russell 2000 has lagged T-bills by more than -10.6% since then. The capitalization-weighted S&P 500 Index has performed better during this period only by driving the price/revenue multiple of the information technology sector to levels that easily exceed the 2000 extreme.

While record valuations, unfavorable market internals, and recurring warning flags have held us to a bearish outlook since the June comment, You Can Ring My Bell, our investment discipline has benefited despite a further market advance since then, partly as a result of the hedging implementation we introduced in the fourth quarter (see the section titled “Good News and Good News” in the October comment, Subsets and Sensibility).

What appears to be an endless bull market advance is actually a classic two-tiered blowoff in speculative glamour stocks. If you missed Bill Hester’s excellent analysis of large-cap market concentration, Slimming Down a Top-Heavy Market, now may be a worthwhile opportunity to recognize how extreme the current situation has become. The chart below offers some sense of how much investors now need to rely on a “permanently high plateau” in valuations.

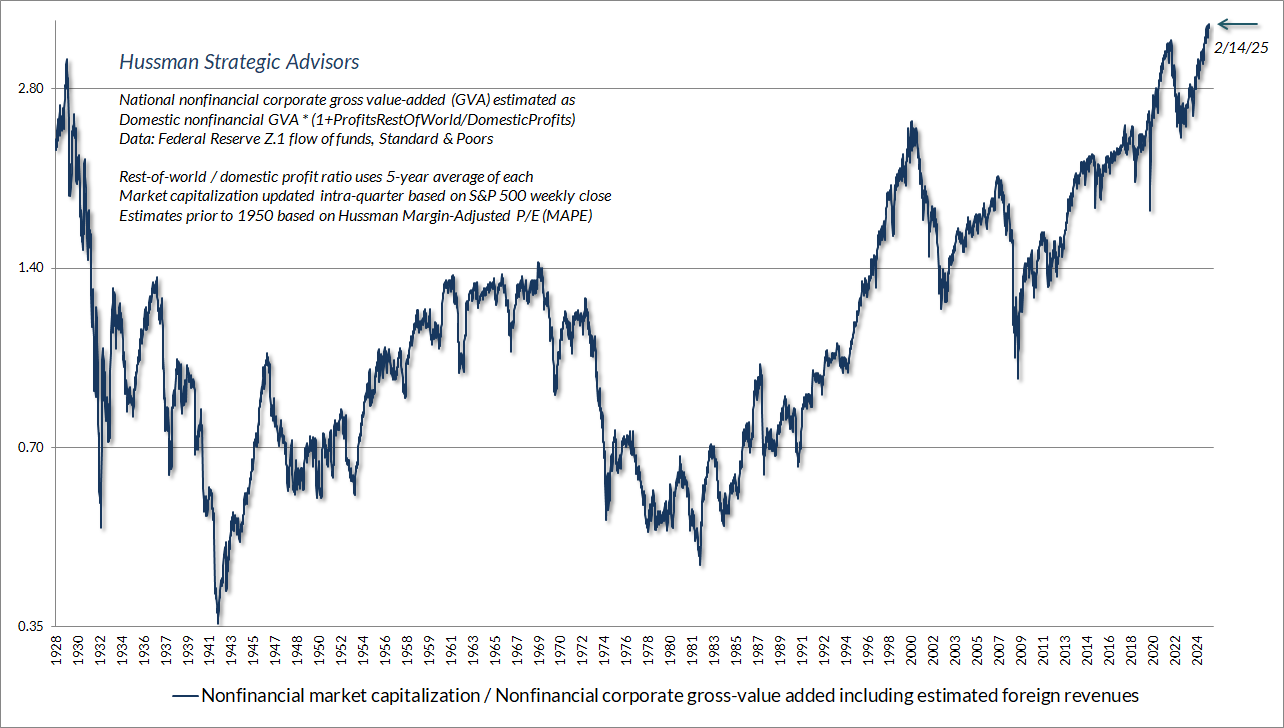

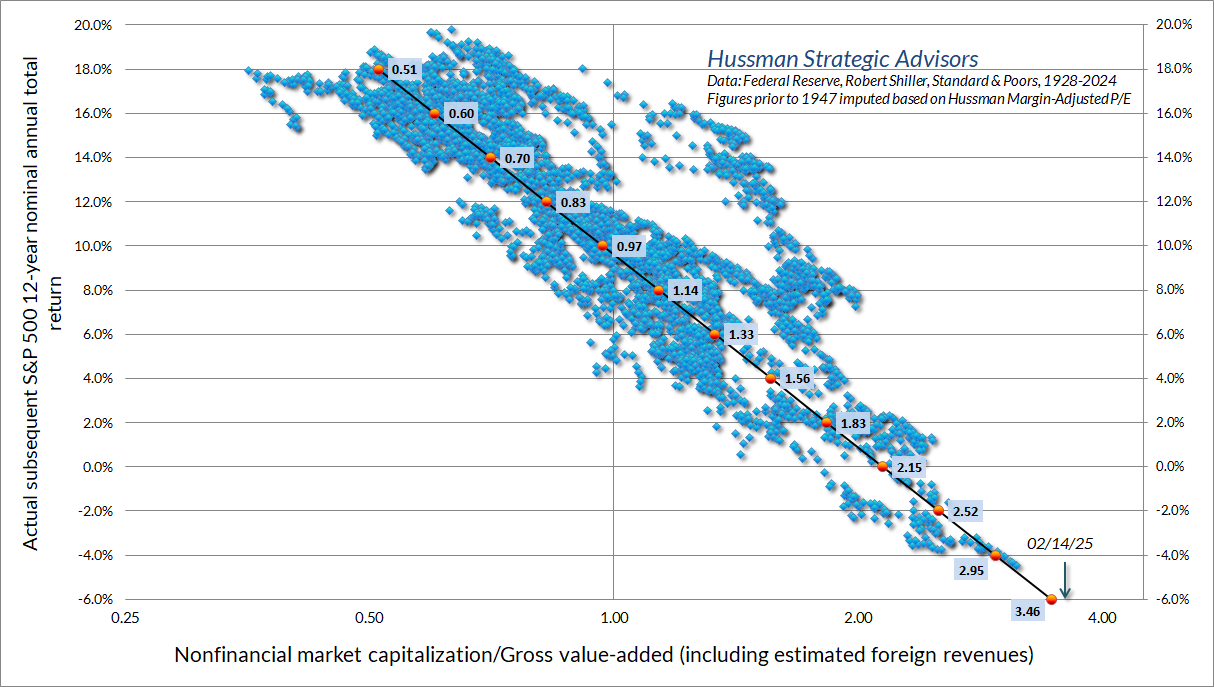

More broadly, the chart below updates our most reliable valuation gauge, based on correlation with actual subsequent S&P 500 10-12 year total returns in market cycles across history. MarketCap/GVA measures the market cap of U.S. nonfinancial corporations as a ratio to their gross-value added – corporate revenues generated incrementally at each stage of production, including our estimate of foreign revenues for these companies. The recent extreme of 3.6 is the highest level in history, exceeding both the 1929 and 2000 market peaks.

To put a level of 3.6 into perspective, the historical norm for MarketCap/GVA is only about 1.0, which is also the level associated with average subsequent 10-12 year S&P 500 nominal total returns of about 10% annually. A reliable valuation gauge is just shorthand for a proper discounted cash flow analysis. The further valuations depart from long-term historical norms, the further subsequent returns are likely to depart from historically run-of-the-mill averages. For a detailed discussion, as well as an analysis of growth rates, profit margins, and their drivers, see You’re Soaking In It.

Investors are welcome to rely on the hope that market returns over the coming decade will be “positive outliers,” rather than the outright losses implied by historical experience. Consider the fact that U.S. nominal GDP, corporate revenues, and gross value-added have all grown at an average rate of about 4.5% annually over the past 10, 20 and 30 years. Since a constant valuation ratio means that prices are growing at the same rate as fundamentals, a continued 4.5% nominal growth rate, plus the prevailing S&P 500 dividend yield of 1.3% would imply average annual S&P 500 total returns of about 5.8% annually – provided that valuation ratios remain at current record extremes forever. So you got that goin’ for ya, which is nice.

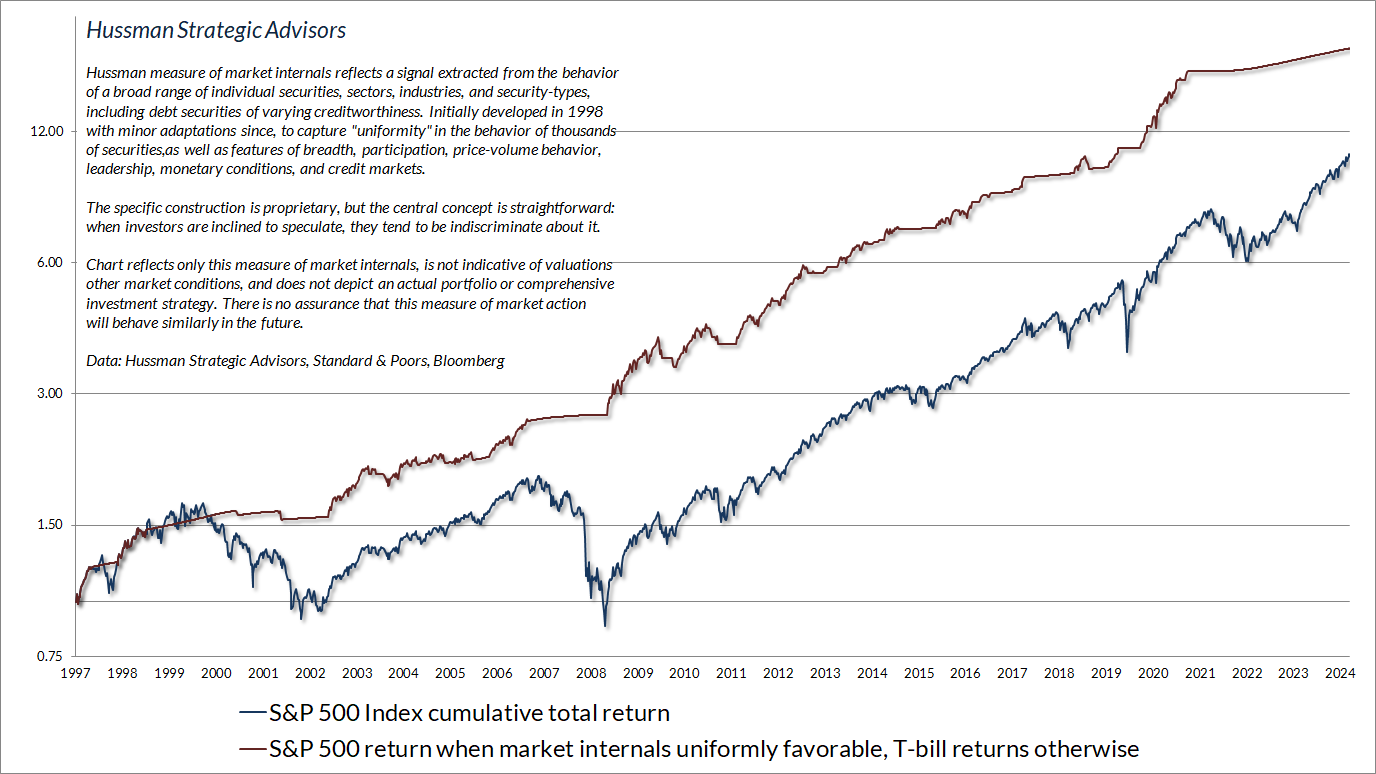

While valuations are extremely informative about likely 10-12 year market returns, as well as the potential depth of market losses over the completion of a given market cycle, valuations are not reliable indications of shorter-term market outcomes. Investor psychology – particularly speculative psychology versus risk-aversion – has an overwhelming impact on shorter-term market outcomes. Since speculators tend to be fairly indiscriminate, and increasing selectivity has historically preceded the most severe market losses, our most reliable gauge of speculation versus risk-aversion is the uniformity of market internals across thousands of individual stocks, industries, sectors, and security-types, including debt securities of varying creditworthiness.

The chart below presents the cumulative total return of the S&P 500 in periods where our main gauge of market internals has been favorable, accruing Treasury bill interest otherwise. The chart is historical, does not represent any investment portfolio, does not reflect valuations or other features of our investment approach, and is not an assurance of future outcomes.

It’s worth repeating that the equal-weighted S&P 500 has outperformed Treasury bills by a cumulative margin of less than 2.4% since the January 2022 market peak. In contrast, the widening dispersion between mega-cap stocks and smaller companies has contributed to a situation where market internals have remained unfavorable, despite a seemingly inexhaustible advance in the capitalization-weighted S&P 500. After testing countless strategies and adaptations aimed at cleverly darting between a defensive outlook and a bullish one amid historically ominous market conditions, the “Eureka moment” was the realization that I was asking the wrong question. The better question was how to vary the intensity of a valid defensive outlook, in a way that can be expected to benefit even in a further advance, provided only that the market fluctuates along the way. Rather than modifying our gauge of internals, which continues to measure precisely what it is designed to measure, we improved our hedging implementation.

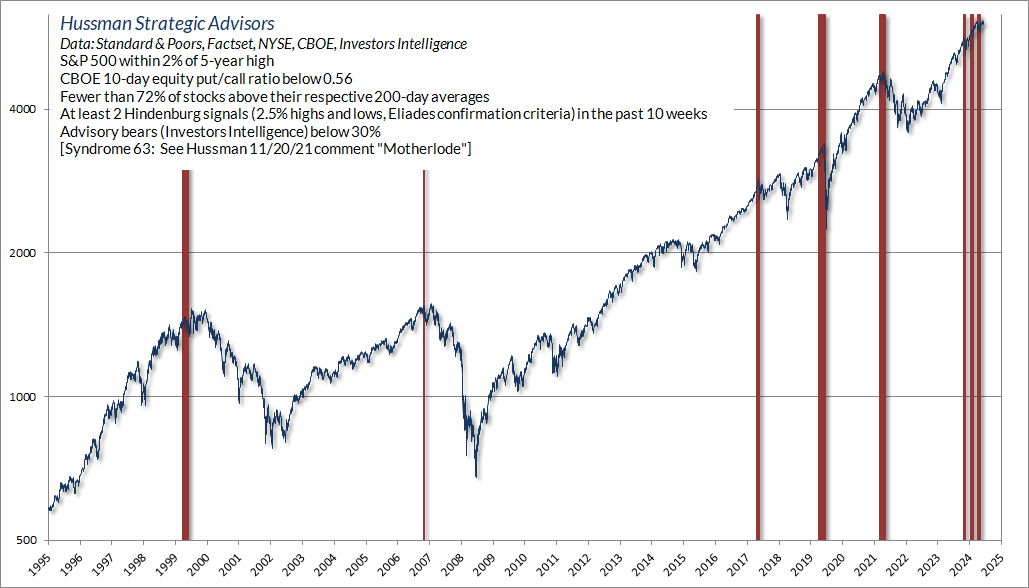

With record valuations joined by unfavorable valuations, we’ve been paying particular attention to shorter-term syndromes of extreme overextension in weekly and daily data. Among scores of syndromes that I’ve developed and catalogued over the past 40 years, the combination below is particularly fun, not least because, in combination, they suggest that stocks have just entered a bear market. As usual, of course, no forecasts are required. Our investment discipline is to align our outlook with measurable, observable market conditions, and to change our outlook as the evidence changes. Still, we’ve seen this combination of syndromes so infrequently across market cycles that it’s worth noting, if only as a curiosity.

As I detailed in the November 2021 comment Motherlode, approaching the January 2022 market peak, “There are certain features of valuation, investor psychology, and price behavior that emerge, to one degree or another, when the fear of missing out becomes particularly extreme and the focus of speculation becomes particularly narrow.”

The first syndrome below is among the many we monitor in daily data. The specific criteria are detailed in the chart text. As with all of these syndromes, the common feature is a combination of overextended price action coupled with divergent market internals, and in some cases, lopsided bullish sentiment.

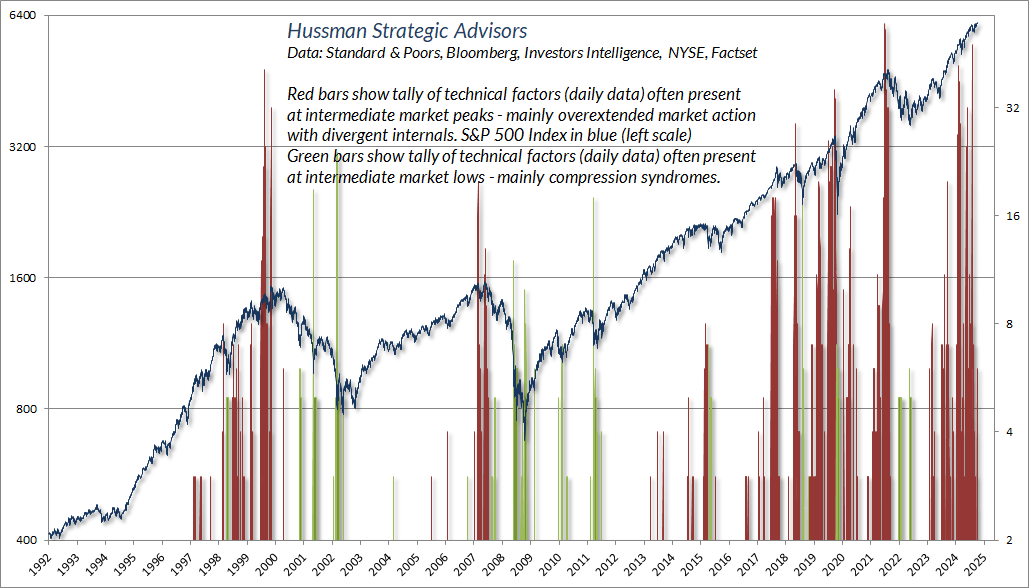

The syndrome above tends to be a bit early, perhaps because it’s big on enthusiasm – particularly involving low levels of bearishness and investor put option activity. That enthusiasm sometimes takes time to exhaust itself. Rather than overly refining these, I simply prefer to track a large number of these syndromes and note when a preponderance of warning flags emerge simultaneously. The red bars in the chart below show our tally over overextended warning flags in daily data. The green bars show our tally of favorable syndromes, mainly oversold “compression” that tends to be relieved by fast, furious “clearing rallies.”

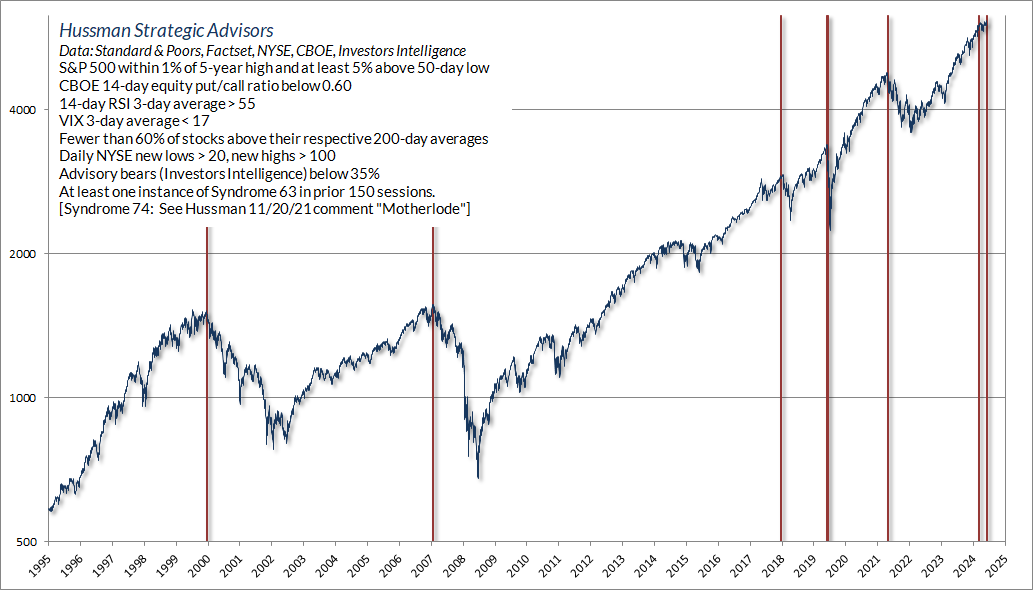

One of the interesting warning flags in recent weeks is the one below. This one requires the S&P 500 to be within 1% of a 5-year high, along with a batch of other features that, as usual, capture a combination of overextension and internal divergence. The 2000 instance was in August of that year, as the S&P 500 briefly approached the bull market peak it set in March. The next instance was on October 9, 2007, coinciding with the market peak that preceded the Global Financial Crisis.

The September 2018 instance was quickly followed by a market plunge in the fourth quarter of that year. The little group in the first half of February 2020 is interesting, because the conditions for a market plunge were in place even before pandemic concerns were widespread. The January 4, 2022 instance coincided with the market peak of that year, and was followed by steep market losses over the following quarters. Finally, we have the two most recent instances. Though the S&P 500 advanced an additional 2% from its initial November 2024 warning to last week’s instance on February 18, I view the two as part of the same top formation, particularly given that the S&P 500 has been riding along the top of its weekly Bollinger bands (2 standard deviations above its 20-period average) for most of this period.

Emphatically, I consider syndromes like this to be “weak sensors,” best used in composites that include scores of them, rather than taken as definitive signals or self-contained investment guidance. There are few things I keep proprietary aside from our gauge of market internals, because nothing in our investment discipline relies on measures like this. By themselves, these syndromes are just interesting toys – fun to monitor, but they shouldn’t be considered outside of far more robust evidence. They’re useful here precisely because so many are kicking in simultaneously, while more robust evidence – particularly record extremes on reliable valuation measures, coupled with unfavorable market internals – is just as negative.

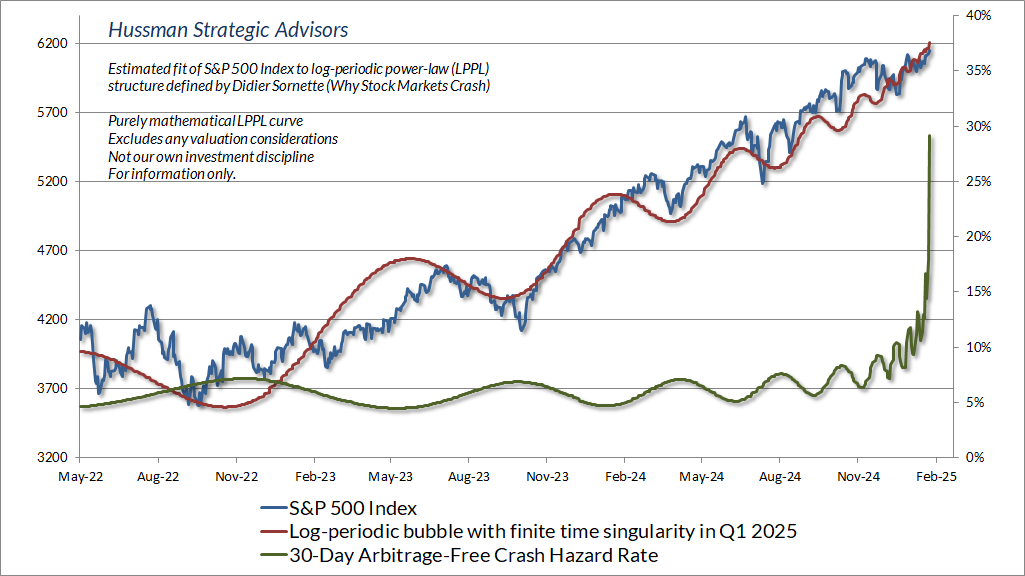

Among other measures that we view more as analytical observations than investment tools, we’re presently seeing the closest example in years of what Didier Sornette described decades ago as a “log periodic bubble.” The basic feature here is a persistent advance that gradually reflects increasingly urgent attempts to “buy the dip” – contributing to the perception that the bubble is relentless and even – to use one of Peter Atwater’s favorite bubble adjectives – “unstoppable.” Again, this is more an observation than a tool, but given that we haven’t seen a structure like this for a few years now, it may be useful to recognize how pervasive investor confidence has become. A market crash, after all, is nothing but risk-aversion meeting a market that’s not priced to tolerate risk.

Rocking a perched boulder

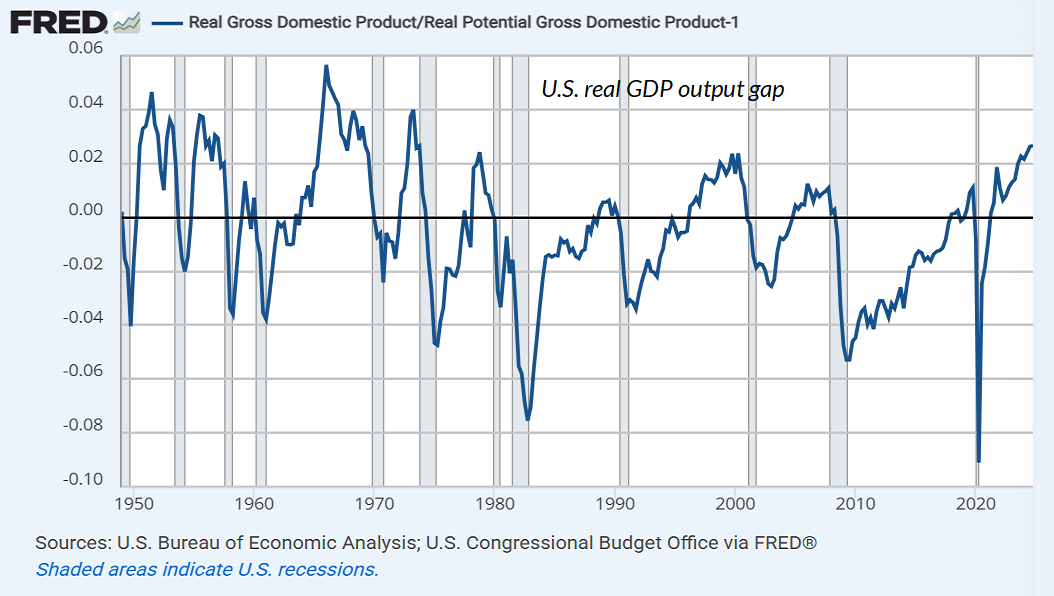

On the economic front, it’s worth reviewing our current position in the economic cycle. Investors may not entirely appreciate is that U.S. real GDP is now running 2.7% above its sustainable full employment potential as estimated by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The CBO estimate is closely aligned with our own estimates that simply use productivity and labor force demographics, so while one might find a little bit of wiggle room in the estimates, real potential GDP has generally been a reliable guide to the general position of the U.S. economy within the economic cycle.

The November comment, The Turtle and the Pendulum, includes a broader discussion of the economic outlook (see the section titled “The structural drivers and prospects for U.S. economic growth”). Below is an updated chart of the current real GDP output gap. Note that positive output gaps are typical in late-stage economic expansions.

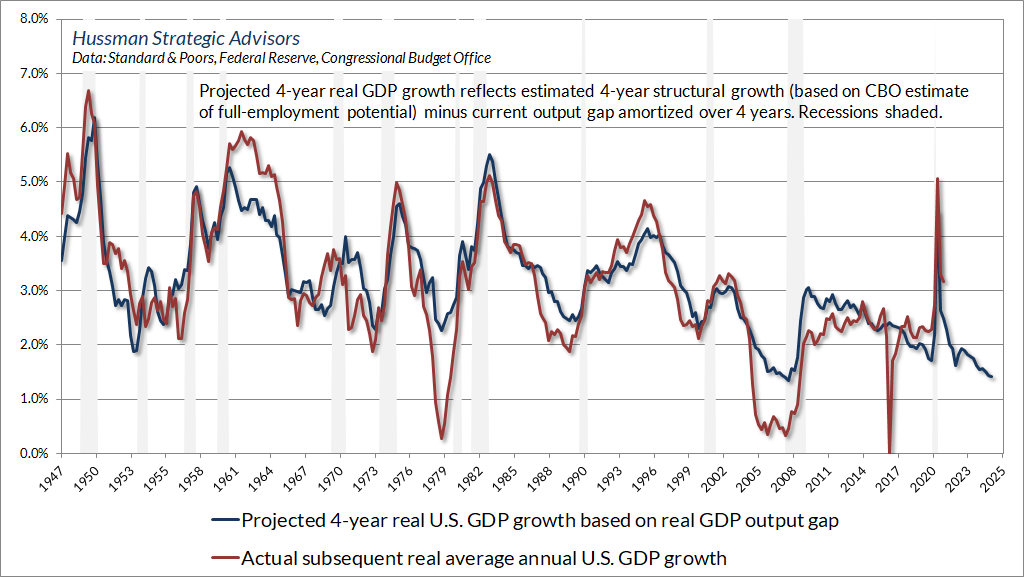

The chart below shows projected 4-year real GDP growth, based on the prevailing GDP output gap, along with actual subsequent 4-year real GDP growth in data since 1947. As I detailed in November, real U.S. GDP growth has progressively deteriorated in recent decades, partly because of lower demographic labor force growth, and partly because of tepid growth in net domestic investment. In fact, net capital investment has declined as a share of corporate revenues over the past 40 years, even while tax reductions and lower interest costs have boosted profit margins.

Keep in mind that the chart above is a “baseline” projection, and that recessions typically produce a striking shortfall from these estimates. Only the projections in the third and fourth quarter of 2007 were lower than the current baseline. From the standpoint of the complete economic cycle, the U.S. economy was already in a vulnerable position before the global financial crisis. In my view, the same is true today.

Recessions are first and foremost periods when a mismatch emerges between what the economy has been producing, and what the economy now demands. Those mismatches can be driven by shifts in consumer preferences, interest-sensitive investment, technology, government spending, credit strains, or crises like the pandemic. Disruptions triggered by these mismatches take time to resolve, absent massive bailouts and deficit spending. It’s not just the direct disruptions, but the broader uncertainty that they produce, that contribute to economic downturns.

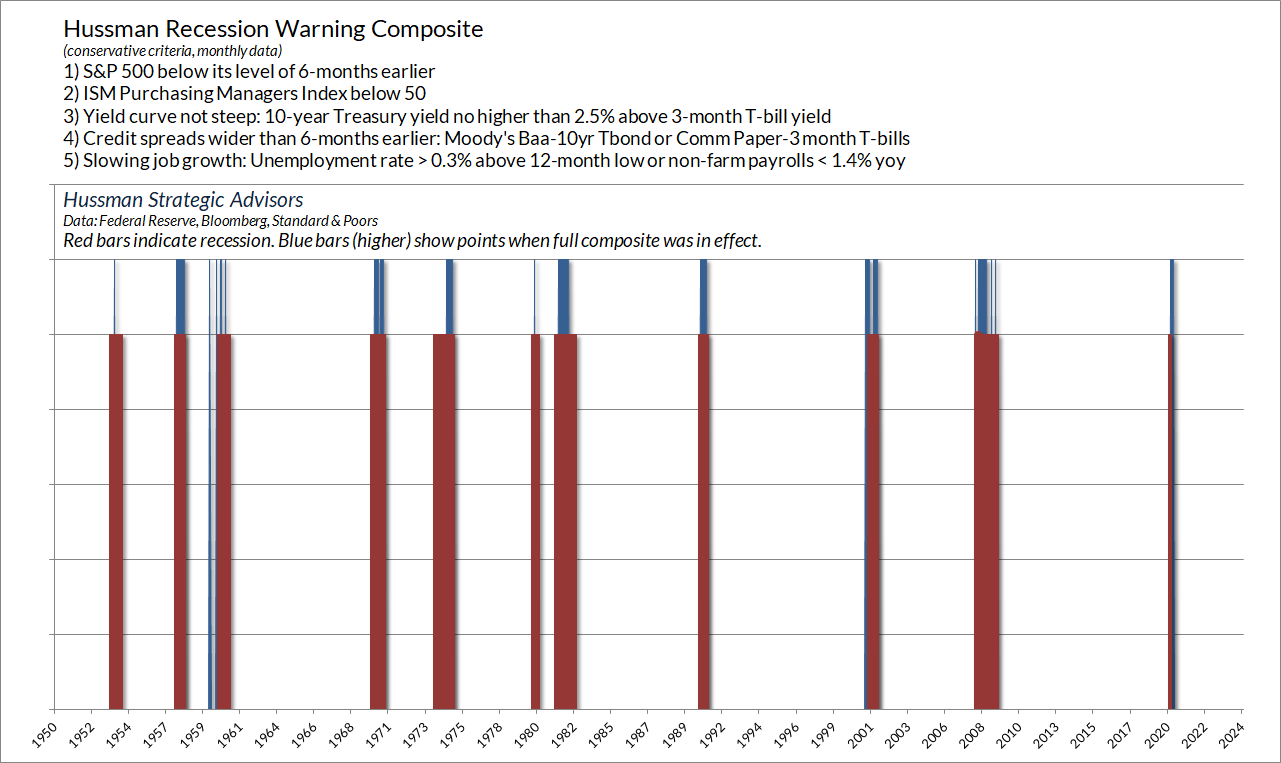

In my view, we’re suddenly soaking in exactly this sort of disruption. Keep your eye on financial markets, credit spreads, and surveys of purchasing managers and consumer confidence. Emphatically, further deterioration would be needed in order to expect a recession with confidence, but the thresholds are surprisingly close. Indeed, just 5% lower in the S&P 500, 15 basis points wider in Baa credit spreads, and 1 point down in the ISM Purchasing Managers Index would be sufficient to move our Recession Warning Composite into the red. More sensitive composites have been hovering at their own thresholds for some time, but they’re prone to occasional false signals. As usual, our preference is to draw a common signal from multiple measures, without relying on any single component. For reference, the chart below shows the basic composite that’s served us well over time. Again, we’re not there yet.

The sound of one hand clapping

It’s sometimes difficult to talk about the securities markets when much of Wall Street seems to be confused about what securities even represent. In other fields, the use of an equals sign brings both precision and clarity. Antoine Lavoisier established that mass is neither created nor destroyed by a chemical reaction. Rudolph Clausius established that energy is never created nor destroyed, but only converted from one form to another. The lowly equals sign does an enormous amount of work in clearing up confusion.

In finance however, we market participants are constantly trapped by assertions like “buying makes prices go up,” and “selling makes prices go down.” We get caught in the notion of self, so we only see one hand clapping. The fact is that every transaction in the financial markets involves both a buyer and a seller. The buyer hands cash to the seller. The seller hands a security to the buyer. The price change depends only on which of the two is more eager.

Likewise, investors are constantly bathed in chatter about “money on the sidelines” that must somehow find a “home” in stocks, or bonds, or whatever, when the reality is that the moment a buyer puts a dollar “into” the stock market, a seller takes that dollar right back “out.” The total amount of “money on the sidelines” doesn’t change. Every dollar of cash and cash-equivalent securities that’s been issued to the public by the Federal Reserve, the Treasury, banks, and corporations must be held by someone at every moment in time. That total goes up when new cash and cash-equivalent securities like Treasury bills are issued. It goes down when those pieces of paper are retired by their issuers. Period.

Every time a market participant takes their savings and provides them to someone who wants to use those savings, a piece of paper is created to memorialize the transaction. It might be an IOU, like a bond or a bank loan, which promises some set of cash flows in the future in return for the money that the saver is putting up today. It might be a stock certificate, which promises some less certain set of cash flows in the future, depending on the success or failure of the venture. It might be a Treasury security, by which the government promises to repay an investor some amount in the future for the savings that the investor lends today. In every case, the piece of paper essentially memorializes an exchange of cash today in return for some set of expected cash flows in the future.

A few principles are enormously helpful in cutting through the noise.

1) Every security that has been issued must be held by someone at every moment in time.

2) Every transaction has both a buyer and a seller.

3) Every security is both an asset to the holder and a liability to the issuer.

4) Securities come into existence when savings are intermediated, and they cease to exist when the liability is finally retired.

5) From the moment a security is issued to the moment it is retired, the total value of that security to the entire series of investors that hold it is measured only by the cash flows that the security throws off to its holders during its lifetime. The intervening price changes don’t create or destroy wealth. They only enable transfers of market capitalization between buyers and sellers, which can later prove to be good choices for one and unfortunate choices for the other.

Investors who internalize these principles can immediately see thorough notions like “investors rotating out of stocks and into bonds,” because they know that every outstanding stock share and bond certificate must be held by someone at every moment in time. If investors want fewer stocks and more bonds, their eagerness toward one versus the other might affect prices and market capitalizations, but there will be just as many stock shares and bond certificates outstanding at the end of trading as there were at the beginning, and they will all be held by someone.

If stock prices go down, we can’t ask “where are investors going to put the money they took out?” because we already know there is not a dollar more nor a dollar less “on the sidelines” as the result of the transaction. It’s true that one group of investors can sell stocks and put the proceeds into a money market fund, allowing everyone to point to “money flow” into that fund – imagining that there’s suddenly more “cash on the sidelines.” But if we’re awake, we also realize that someone bought the stocks that were sold, using cash they held already. That side of the transaction has just been ignored.

Every single dollar of cash and cash-equivalent securities that the U.S. government and other issuers have created must also be held by someone, at every moment in time. There is no “getting out of cash” or “getting into cash” in aggregate.

Of course, any individual investor, fund, or portfolio does have the ability to change their own cash holdings. So while it’s nonsense to imagine that “cash on the sidelines” can “find a home” or become anything but itself, it can be very useful to ask a different question: Who’s holding the cash?

On that front, my friend Jesse Felder recently shared an interesting contrast. The latest survey by Bank of America reports that the average cash level in the portfolios of global fund managers is just 3.5%, one of the lowest levels on record, while their economic confidence is at multi-year highs, with 82% seeing no recession on the horizon. Fund managers tend to hold minimal amounts of cash at market peaks and – except when high interest rates create a clear incentive to hold cash – managers tend to hold the highest cash levels at market lows. The average cash level of fund managers is now lower than even the 3.8% reading that BofA described in December as a “contrarian sell signal.” Meanwhile, Warren Buffett’s company has been a net seller of stocks for eight consecutive quarters. Berkshire Hathaway presently holds the highest level of cash, as a percentage of assets, on record. Which one do you want to follow?

The government deficits land in the deepest pockets

The ability to see both sides of an equilibrium is just as useful when we think about savings, investment, deficits, and profits. Consider total U.S. output: all the goods and services produced by the U.S. economy. From an output perspective, the amount of goods and services not used for “consumption” by households, government, or foreign trading partners is labeled “investment” – even if it’s unsold inventory investment. From an income perspective, the amount of income not used for “consumption” is labeled “saving.”

Since output and income are just different ways of accounting for U.S. economic activity, it shouldn’t be surprising that “saving” is equal to “investment.” That’s not a theory. It’s just an accounting identity.

Of course, the people who do the “saving” out of income may not be the same people who do the “investment” in tangible objects like capital goods, factories, and equipment. If some sectors in the economy are running deficits (where their consumption and net investment exceeds their income) and others are running surpluses (where their income exceeds their consumption and net investment), new securities will be created in order to transfer the savings from one party for use by the other.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that if you add up the deficits and surpluses across all sectors of the economy – households, corporations, government, and foreign trading partners – the total is zero. If the government is running huge deficits, other sectors of the economy, in total, must be running huge surpluses. Again, that’s not a theory. It’s an accounting identity.

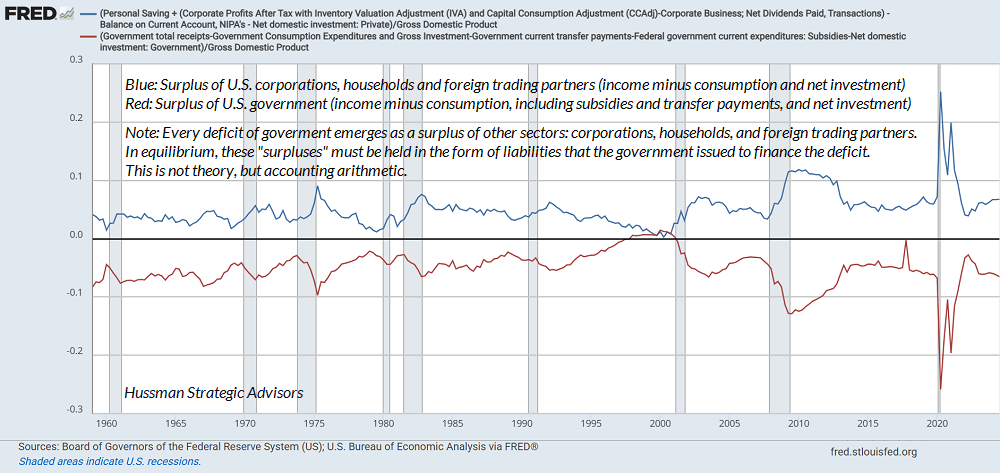

The chart below shows how this works. The blue line is the “surplus” – income minus consumption and net investment – of U.S. corporations, households, and foreign trading partners. The red line, generally in negative territory, is the “surplus” of the U.S. government.

Put simply, every deficit of government emerges as a surplus of corporations, households, and foreign trading partners (income over and above their consumption and net investment). A government deficit means that it has spent, allocated, or consumed more goods and services than its income from tax revenue could finance. That also means that some other sector of the economy produced more goods and services than it consumed, and essentially traded that output to the government (or indirectly, the beneficiaries of that government spending). What do those “savers” get in return? Newly issued government liabilities. In equilibrium, the deficits of government emerge as the surpluses of other sectors, and those new “surpluses” are held by savers in the form of whatever liabilities (Treasury securities and newly created money) the government issued to finance its deficit.

From 2016 through 2020, $8.4 trillion in new 10-year deficit spending was approved – a combination of tax cuts and net spending increases, with about $3.6 trillion of that related to pandemic response. From 2020 through 2024, another $4.3 trillion in 10-year deficit spending was approved, about $2.1 trillion of that being pandemic response (Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget). Government deficits, again, are always matched by surpluses in other sectors. In recent years, the primary beneficiaries have been business profits and household savings, though the household savings have gradually been spent down, largely becoming business profits as well.

With regard to the record ratio of financial market capitalization to GDP, the government deficits of the past eight years have bloated the corporate profits on which investors are placing extreme price/earnings multiples while calling it “stock market capitalization.” Meanwhile, the highest income earners have also accumulated the cash and securities that the government issued to finance the deficits. As a result, the massive deficits of recent years are a significant portion of what the deepest pockets presently call “wealth.”

While both the federal debt and federal deficits have declined since 2021, as a share of GDP, even deficits of the present size are unsustainable. Still, it matters enormously how the shortfalls are created. What matters isn’t only whether one borrows, but how revenue is obtained, and how the funds are spent. Long-time readers may recall that I advised members of Congress during the pandemic, and suggested that recovery of subsidies should be largely based on actual economic damage sustained during that crisis. Instead, many businesses received PPP subsidies even though they continued to operate without any shortfall in business, while profit margins soared. As I’ve detailed previously, much of the government support acted as a pure subsidy to corporate profits.

I’m sorry, but there’s a certain irony in the ruse of billionaires consolidating their power under the pretense of “reducing deficits” when it’s exactly the massive deficits of recent years that have boosted their income, profits, and financial market “wealth.” There’s a certain irony to see foxes with mouths full of feathers claiming that they’re defending the henhouse; minding the store while their fingers are deep in the cookie jar of government contracts and foreign quid pro quo. They’re selling a house of cards, and everybody’s merrily picking out furniture.

With regard to the record ratio of financial market capitalization to GDP, the government deficits of the past eight years have bloated the corporate profits on which investors are placing extreme price/earnings multiples while calling it ‘stock market capitalization.’ Meanwhile, the highest income earners have also accumulated the cash and securities that the government issued to finance the deficits. As a result, the massive deficits of recent years are a significant portion of what the deepest pockets presently call ‘wealth.’

It adds insult to injury to propose that corporate taxes should be reduced even further, despite the fact that higher corporate profit margins in recent decades have been associated with decidedly lower net business investment as a percentage of revenues. I’ll leave it to conscience to justify it as reasonable to cut meager support for humanitarian aid, social services, medical research, students with disabilities, and other vulnerable populations in order to finance further tax reductions, disproportionately for the wealthy, when 67% of U.S. net worth is already held by the top 10% of Americans and only 2.5% is held by the bottom 50%. Meanwhile, 50% of U.S. equities are held by the top 1% of income earners, with 87% held by the top 10%. Only 1% of U.S. equities are held by the bottom 50%.

Among the pseudo-analyses making the rounds is that a report last year from the General Accounting Office “found” government fraud amounting to $233-521 billion a year. The fascinating aspect, if one actually reads the report, is that this figure isn’t actually a finding at all. It’s a model simulation, based on arbitrary assumptions that explicitly rejected informed input, statistically valid sampling, or data analytics.

That’s not to say that there isn’t fraud in government spending. Indeed, confirmed fraud, as reported by the Office of Management and Budget, amounts to several billion a year: $7.3 billion in the pandemic year of 2020, $4.5 billion in 2021, and $4.4 billion in 2022. Given federal outlays on the order of $7 trillion, much more likely goes undetected. That’s certainly a reason for careful accounting and auditing. It’s not a justification for slash-and-burn by a brigade of drunk guys from the end of the bar ranting about the guvmint. I’ll say this – if one is looking for waste in government, the place to start would be billion-dollar government contracts with corporations, not experienced, career federal workers that comprise less than 1% of the population and less than 2% of the civilian labor force – half the 1950 level and close to the smallest share in U.S. history. The point of the firing isn’t to save money, it’s to install loyalists.

This isn’t who we are

Some people prefer me to “stay in my lane,” but here’s the thing – I went into finance over 40 years ago for two reasons: to serve long-term investors, and to fund efforts to reduce the suffering of vulnerable populations, much of it toward disease eradication, disability, poverty, basic education, homelessness, hospice care, and communities uprooted by conflict. Most of what I’ve earned across decades of market cycles – becoming a leveraged bull after the 1990 plunge, anticipating the tech bubble collapse, navigating the mortgage bubble and its collapse – has gone to those efforts. We’ve been able to do less during the bubble of recent years, though we’ve adapted enough that I expect our work to thrive over the completion of this cycle. In the meantime, as long as I have a voice, I would consider silence in this moment to be a betrayal of the vulnerable communities that we call partners.

Call me naïve, but I still believe that Americans are more alike than different. I think we’re getting played, misdirected by wildly-amplified divisions that have made many of us willing to surrender rule of law, balance of power, human rights, and the defense of democratic allies, while allowing and even encouraging billionaires to enrich themselves at the expense of the vulnerable. We’re fed a constant slideshow of extremes, curated by algorithms, bots, and outrage theatre masquerading as news, that convince us that the worst extremes are representative of the other “side.” Our world is stretched, bent, and distorted by fun house mirrors, and we tell ourselves that we’re only believing our own eyes.

By now, some of us are so angry at the other “side” that we’re perfectly willing to dehumanize others if we can be sold on the idea that cruelty is justice. Retribution. Somehow our divisions have allowed us to buy into the idea that greatness means tolerating an America that abandons its allies, embraces authoritarianism, contemplates the potential benefits of ethnic cleansing and territorial expansionism, elevates parasitic extraction to a core value in foreign relations, and approaches change as a matter of torches, pitchforks, and chainsaws, wielded against the enemy du jour.

This isn’t who we are.

Last week, Theunis Bates, the Editor-in-Chief of The Week observed, “it has become apparent that America is not simply moving past the excesses of progressivism – the compulsory stating of pronouns, the hawking of anti-racism books for babies, the pretending that Emilia Perez is a good movie – but beyond the idea that it’s good to care for others at all. On social media, people have rejoiced at the slashing of U.S. food aid and medicine for people suffering genocide and famine. Musk once told his biographer how his favorite video game had taught him the ‘life lesson’ that ‘empathy is not an asset.’ We’re now seeing what happens when that mantra becomes a governing philosophy.”

This isn’t who we are.

As imperfectly as we’ve pursued our ideals, America has fundamentally stood up for the idea that we share a common humanity, that all of us are connected by common thread that asks for little but decency toward each other, and to promote the general welfare, realizing that “us” could easily have been “them” if the circumstances, wealth, race, or simple realities of our of birth had been different. The world has admired America, and we’ve had pride in ourselves, not because of race, religion, party, wealth, or even common roots, but because we stood for the idea that government by the people – not a despotic, throne-obsessed monarch – and respect for the equal rights of other human beings were self-evident. We’ve failed at that vision a thousand ways, but we’ve never abandoned it. We can’t abandon it now if we hope for America to endure as anything approaching “great.”

“Long live the King.” Sure, and I’m Batman. This isn’t who we are.

My friend Ben Hunt recently described the situation this way: “For the better part of two centuries (I put the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 as my starting point) the United States has tried – sincerely tried as a common goal and as a prominent semantic signature existing through and across political lines – to be both a Great Power and a Good Power. Trumpism is an embrace of America as a Great Power and a rejection of America as a Good Power, in all its forms, both domestic and internationally. More than that, it is an ideological embrace of America as a Great Power, that this is everything America should be, and an ideological rejection of America as a Good Power, that this is something America should never be… I absolutely think this is a tragedy, because the pursuit of great power for great power’s sake transforms every American policy, both foreign and domestic, into a protection racket of one form or another.”

This isn’t who we are.

Only by saying that, out loud, and standing up for it again and again, can we avoid becoming something else entirely.

On Governance

Reprinted from the Jan 30, 2017 comment – because we’re allowing this to become institutionalized

Those who aspire to “right speech” often measure their words with four questions: Is it true? Is it kind? Is it necessary? Is it the right time? Right speech should not escalate conflict, but it doesn’t retreat from necessary truth, and criticisms don’t always seem kind. The question of right speech is the question of how one might best serve others. Criticism with the intent to offend is not constructive, but silence is equally detrimental when it quietly endorses a pattern of offense, or encourages the silence of others.

Those of you who have followed my work over the decades know that I look at the world holistically in terms of the interconnection and responsibility we have toward others, and I’ve never been much for separating “business” from those larger values. After all, most of my income regularly goes to charity, and nearly everything that remains follows our own investment discipline. Whether my comments on matters like peace, civility, economic policy or governance are well-received or not (and I’m grateful that they have been over the years), there are moments when one has the responsibility to speak if one has a voice.

Our country faces many legitimate political disagreements. There are segments of America that view government as too bureaucratic, see foreign trade as a source of job insecurity, value national security as a priority, believe that each country has the right to a national identity, and feel that even a nation of immigrants has limits on the pace at which it can assimilate new citizens. They feel that their interests have been subordinated to an elitist philosophy that presumes that regulation is always beneficial, and that government always knows best. Those who value conservative policies have a right to advocate for them, and to support candidates who represent their interests. We can engage honestly and in good faith about those concerns, even where we disagree. Political issues like that are best settled not by insulting each other, but by openly expressing and listening to the values and concerns of each, and constructing solutions where each side might concede or trade various lower priorities, so that both can achieve their higher ones.

From my perspective, the problem isn’t politics. A civil society can work out those differences. The immediate problem, and the danger, is the mode of leadership itself. A leader can call forth either the “better angels of our nature” or the worst ones. I am troubled for our nation and for the world because of the example of coarse incivility, mean-spirited treatment of others, disingenuous speech, thin temperament, self-aggrandizing vanity, puerile character, overbearing arrogance, habitual provocation, and broad disrespect toward other nations, races, and religions that is now on display as our country’s model of leadership. Despotism reveals itself through a reliance on threat, intimidation, bullying, coercion, and a chilling instinct to address problems through forms of termination, such as the killing of enemies and the exclusion and dismissal of adversaries. I am equally troubled by emerging risk, discussed below, to the Constitutional separation of powers.

My intent is not to insult, but rather to name the elements of this pattern. Even in the face of our differences, it’s important that we refuse to resign ourselves to passively accepting or normalizing this model. A dismissive regard for truth, civility, transparency, ethics, and process is dangerous because it lays groundwork and creates potential for unaccountable, corrupt and arbitrary government. I believe that the people of our nation are both decent and vigilant enough to openly and loudly reject this behavior even where they might agree with various policy directions.

It strikes me that because the U.S. is a relatively young nation, we are less inclined to recognize seeds that can grow into abuse of power, because the worst examples we recall across history have been in other nations. The progression thus far rhymes more than I’d like. I think it would be wrong to abandon vigilance and scrutiny, particularly where various proposals could have the effect of weakening the separation of powers between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

There is no changing the outcome of what was already a dismal choice for many Americans, but we can insist on rejecting a model of uncivil behavior. It is unworthy of emulating for ourselves, much less for our children. To minimize detestable behavior is essentially to condone it. It is the refuge of cowards to defend obvious offenses by deconstructing them (“He wasn’t belittling a disabled person. See? He’s waving his hands while belittling this person too”), or to condone predatory behavior toward women by diffusing responsibility (“Yeah, but that other guy was also a predator”). Our intolerance for such a tireless pattern of offense shouldn’t depend on our race, or gender, or ability, or political views, even among those who view the man as a means to achieve political ends.

Meanwhile, we should recognize that foreign provocation has also been used around the world, and throughout history, as a strategy to expand domestic control. This often takes the form of “emergency powers.” Given the man’s clear aspiration to accrue and exercise authority, we shouldn’t naively ignore that potential. Recalling James Madison, “If tyranny and oppression come to this land, it will be under the guise of fighting a foreign enemy. The means of defense against a foreign danger historically have become the instruments of tyranny at home.” We have a leader that talks of the benefits of foreign plunder and the virtues of torture, yet we don’t recognize the seeds of despotism? Oh, that’s right, because we’re talking about the “enemy.”

The enemy. It’s necessary to prosecute those who commit violence, in order to defend the rights of others, but to entertain notions such as torture, plunder, and the violation of human rights is an insult to the virtues our nation has sacrificed so much to achieve. Hatred does not remove hatred. We have to look into causes and conditions. Prejudice against a whole religion will not bring peace, nor will it contribute to an understanding of what motivates extremism. Whether the roots of violence are about foreign influence, territorial control, fear of losing power, protecting an existing way of life, or perceptions of injustice (whether legitimate or imagined), violence is often clothed in religion, both as a mobilization tactic, and so each side can claim that God is on their side. ISIS is no more about Islam than the Troubles in Ireland were about the religious faith of Catholics or Protestants, or the KKK was about Christianity.

We can’t kill and torture our way to peace. We might satisfy pride and the desire for revenge, but the outcome would be a perpetual cycle of hatred, where our children eventually take our place in that cycle. The temptation is for sides both to turn up their high-beams, but as the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King implored, “Someone must have sense enough to dim the lights.” Again, yes, those who actually commit violence should justly be prosecuted, but it’s madness to make enemies of entire populations. Along with enforcement against violent extremists, it’s essential to seek out and address the legitimate concerns of moderates. The first step toward peace happens when somebody has the courage to look deeply and ask, “How does the person I call my enemy suffer, and what can I do within my power, and consistent with my security, to address that suffering?”

We are asked to rally around our new Administration, in the hope that it will be successful. Yet if, even at the outset, “success” asks us to accept the insult to loyal allies; if it asks us to accept daily incivility toward other citizens of our country; if it asks us to accept a demonstrably ill-conceived economic dogma that will do little but provoke trade frictions, weaken domestic investment, and provide tax benefits to the business sector, while indiscriminately shifting the costs and externalities of harmful action onto the public and the environment; if it asks us to accept blind prejudice toward other nationalities and religions; and if it flirts with even the prospect of foreign plunder and torture, then there is little question that we have already lost.

A final concern relates to the separation of powers and the relationship between the express will of the People and the actions of the Executive. When the founders of this nation established the separation of powers in the U.S. Constitution, they were serious about it. Over time, through lack of vigilance, the public has allowed this separation to be undermined, to the point where people hardly recognize when violations occur. Here is a reminder. Article I Section I places all legislative powers with Congress. Article I Section 7 provides that all bills for raising revenue originate in the House of Representatives, which are then amended by the Senate. Article I Section 8 provides that only Congress has the power to declare war. Article I Section 9 provides that no money may be spent that is not pursuant to a law enacted by Congress.

The Executive branch has the obligation under Article II Section III to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Under Article II Section II, only after a war is declared by Congress, or the militia are called forth by Congress, does the President have the authority to direct military actions, though Congress has adopted various acts over time that have weakened or abdicated that authority. In order to carry out the obligation of Article II Section III, the President may very well issue executive orders, but those orders are not laws in themselves. They are directives that apply only to members of the executive branch, for the purpose of upholding and faithfully executing existing laws previously passed by Congress.

If an existing law infringes on the rights of the people, or overreaches the powers enumerated in the Constitution, the role of the Supreme Court is to adjudicate those disputes. If an executive order or an agency’s interpretation of an existing law is challenged, the Court has previously articulated a two-part test: if the intent of Congress is clear, the Court should “give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress.” If the intent of the law is ambiguous, the Court should examine whether the interpretation is a permissible construction.

What I find alarming is that recent executive orders have been announced as new proclamations, instead of faithfully executing the provisions of existing laws duly enacted and funded by Congress under Article I of the Constitution. While the formal language of the orders themselves might reference existing laws, or give lip-service with the phrase “to the extent permitted by law,” the orders then self-contradict by directing the circumvention of those laws (for example, “to the extent permitted by law,” agencies are directed to “waive, grant exceptions from, or delay” the execution of the law, or to identify sources of funding for a project that is nowhere specified in the law).

To ask “Where was this criticism during the past 8 years?” is to ignore the distinction between the faithful execution of laws one may dislike, and the invention of provisions that do not exist under prevailing law, which is what we now observe. The worst offender in prior years was not our former administration. It was the Federal Reserve, as Ben Bernanke created off-balance sheet “Maiden Lane” shell companies to purchase assets prohibited by law, in violation of Sections 13 and 14 of the Federal Reserve Act, making what he called “a money-financed gift to the private sector.” Nobody recalls my silence. Congress later rewrote those sections to spell them out like a children’s book.

Even the media fail to discuss the fact that the Executive is both obligated to, and constrained by, the express will of the People, not the other way around. Only when Congress passes a law does it become the law of the land, provided it is otherwise Constitutional. To allow a weakening of these separate and enumerated powers is to invite the arbitrary exercise of authority, and even the risk of tyranny, rather than limited, representative government of the people that honors the Bill of Rights, equal protection, and the rule-of-law.

I understand that facts are facts, and that this is the election result that our system produced. So what is the point, or the desired outcome, of protest? The fundamental outcome is to raise our vigilance; to preserve our character; to defend the rule of law and the separation of powers; to refuse to normalize or quietly endorse incivility; to promote diplomacy even as we pursue security; to demand more than the example set before us; to call us again and again to the better angels of our nature.

We should voice our full expectation that Congress defend those enumerated powers, unmoved by speeches that assert the right of the executive to bind our nation to some “new decree” (who uses the word “decree” in an inauguration speech?) We should also ask that regardless of party, our representatives exercise those powers with dignity that befits our nation. As for individual issues, remember that the laws of our country are not established by tweets in the middle of the night. They are established by Congress. Citizens lose their voice when they fail to use it. All of us, left, right, or moderate, should protect that freedom. The U.S. Senate switchboard is (202) 224-3121. The U.S. House switchboard is (202) 225-3121. An actual person will answer, and can direct you to your state representative. Feel free, also, to forward or reprint these comments as you wish.

Keep Me Informed

Please enter your email address to be notified of new content, including market commentary and special updates.

Thank you for your interest in the Hussman Funds.

100% Spam-free. No list sharing. No solicitations. Opt-out anytime with one click.

By submitting this form, you consent to receive news and commentary, at no cost, from Hussman Strategic Advisors, News & Commentary, Cincinnati OH, 45246. https://www.hussmanfunds.com. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact.

The foregoing comments represent the general investment analysis and economic views of the Advisor, and are provided solely for the purpose of information, instruction and discourse.

Prospectuses for the Hussman Strategic Market Cycle Fund, the Hussman Strategic Total Return Fund, and the Hussman Strategic Allocation Fund, as well as Fund reports and other information, are available by clicking Prospectus & Reports under “The Funds” menu button on any page of this website.

The S&P 500 Index is a commonly recognized, capitalization-weighted index of 500 widely-held equity securities, designed to measure broad U.S. equity performance. The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is made up of the Bloomberg U.S. Government/Corporate Bond Index, Mortgage-Backed Securities Index, and Asset-Backed Securities Index, including securities that are of investment grade quality or better, have at least one year to maturity, and have an outstanding par value of at least $100 million. The Bloomberg US EQ:FI 60:40 Index is designed to measure cross-asset market performance in the U.S. The index rebalances monthly to 60% equities and 40% fixed income. The equity and fixed income allocation is represented by Bloomberg U.S. Large Cap Index and Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Index. You cannot invest directly in an index.

Estimates of prospective return and risk for equities, bonds, and other financial markets are forward-looking statements based the analysis and reasonable beliefs of Hussman Strategic Advisors. They are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of the prospective returns of any of the Hussman Funds. Actual returns may differ substantially from the estimates provided. Estimates of prospective long-term returns for the S&P 500 reflect our standard valuation methodology, focusing on the relationship between current market prices and earnings, dividends and other fundamentals, adjusted for variability over the economic cycle. Further details relating to MarketCap/GVA (the ratio of nonfinancial market capitalization to gross-value added, including estimated foreign revenues) and our Margin-Adjusted P/E (MAPE) can be found in the Market Comment Archive under the Knowledge Center tab of this website. MarketCap/GVA: Hussman 05/18/15. MAPE: Hussman 05/05/14, Hussman 09/04/17.