Entire contents copyright 2003, John P. Hussman Ph.D. All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Brief excerpts from these updates (no more than 1-2 paragraphs) should include quotation marks, and identify the author as John P. Hussman, Ph.D. A link to the Fund website, www.hussmanfunds.com is appreciated.

Sunday June 29, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations and favorable trend uniformity, holding us to a constructive position.

As I've frequently noted over the years, there are few occasions when I have any expectation at all regarding short-term market action, with two exceptions. One is when the market becomes overbought in an unfavorable Climate. Such points are frequently followed by near-vertical drops. We saw exactly that sort of action several times during the past three years. The second is when the market becomes oversold in a favorable Climate. Such points are frequently followed by leaping advances as short sellers suffer a tight squeeze. These advances are not certainties, but there is no set of conditions that produces a higher short-term rate of return on average than an oversold status in a favorable Market Climate. That's exactly what we have today. We'll see.

Last week, I noted that we had taken a few more defenses on the basis of some initial divergences, and that I expected to lessen those defenses if the market produced "clean" action on a decline. A number of things fell into that description last week. First, new lows did not significantly expand on the decline, and trading volume was restrained. The CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) did not increase sharply (contrary to popular misconception, a low VIX is not a danger signal in itself - the main concern is when it breaks into an uptrend from a low level, which has not occurred). Transport stocks, one of the blemishes from the standpoint of Dow Theory, were among the most resilient areas of the market last week, and I wouldn't take the weak non-confirmation of the early June high as sufficient evidence to ignore the more important favorable confirmations that Dow Theory has already provided since the March lows. Lowry's analysis of trading volume also suggests that the pullback was largely driven by a relaxation in buying interest rather than an acceleration of selling pressure. Bonds fell apart, but that was expected in our work, and is unlikely to dampen the stock market outlook until long-term bond yields rise a half percent or more from here.

In short, market action was very "clean" last week on a number of dimensions, and given that the market has cleared its overbought status all the way to an oversold one, we took a moderate position in call options. That places our overall position in Strategic Growth as follows: we remain fully invested in favored stocks, with a modest "straddle" - a total of roughly 2% of portfolio value - in both call and put options. A straddle is effective here because the implied volatility of the options is quite low, and because our main interest is in large market movements - hedging part of our market exposure if stocks were to unexpectedly plunge, but adding to our market exposure in the more likely case (at present) that the market advances. Aside from the portion of our market exposure that we choose to leave unhedged, the main risk of this position is time decay in the value of our options. This risk would arise mainly if the market moves sideways without volatility in the coming months.

As a technical note, even if the overall change in the market is zero over the life of the options, it is possible to "gamma scalp" enough value to cover the cost of the options so long as the actual volatility of the market matches or exceeds the volatility that is implied in the time premium (this involves changing strike prices, hedge ratios, or expirations as the market fluctuates). For that reason, an option only incurs a "hedging cost" in a sideways market when the holder is passive, or when implied volatility priced into the option exceeds actual volatility over the life of the option.

It's not clear at this point how long we'll hold a straddle position, but the combination of low implied volatility (VIX) and an oversold condition in a favorable Market Climate creates an unusual opportunity to take an investment position with curvature. In the event of a sharp market advance, I would expect our position to participate strongly. In the event of a sharp market decline, I would expect our position to have a smaller sensitivity to market risk than a fully invested position would. Again, the main risk is an extended sideways market on low volatility, in which case we would lose the limited amount of time premium on these options. As usual, this position is fully aligned with the prevailing Market Climate, in a way that I believe closely reflects both the opportunities and risks at present.

One might ask why we should hold put options at all at this point, given that the Market Climate is favorable. The answer is risk management. Investment positions should reflect a reasonable balance between expected return and potential risk. The fact that the expected return is favorable does not mean that downside risk does not exist, particularly given current valuations. We never want to take an investment position that relies on a particular market outcome, and results in unacceptable risk if that outcome does not occur. The essential consideration is balance.

That said, I certainly would not over-emphasize the possibility of an abrupt decline. Though our position allows for the possibility to some degree, I would be somewhat surprised if it occurred from present conditions. Such action is simply not typical of favorable Market Climates. Indeed, every historical crash of note has occurred in a climate of both unfavorable valuations and trend uniformity, and most extreme declines are actually accelerations of declines that have been going for quite some time, not abrupt plunges from fresh highs.

Probably the two most frequent questions that run through my mind in the day-to-day management of the Hussman Funds are: "What is the opportunity?" and "What is threatened?" The idea is not to make pointed forecasts about the market, nor to react to what the market is doing. The idea is to constantly review our existing holdings as well as the potential investments available to us, and to respond to what we observe following a very specific discipline. For example, we try to buy higher-ranked candidates on short-term weakness. We try to sell lower-ranked holdings on short-term strength. This is responding, and it stands in stark contrast to reacting. At present, I believe that our positions nicely respond to both the opportunities and the risks present in the markets.

![]()

Sunday June 22, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations and favorable trend uniformity, holding us to a constructive position. Market action has become somewhat tired in recent weeks, however, so we would certainly allow for a moderate correction. As usual, this is not a forecast.

There are three aspects to the market environment that do merit close attention here. The first involves a small set of initial divergences that have emerged in market action. Nothing serious yet, but we're always vigilant. To take an example related to Dow Theory, despite the recent new highs in the Dow Industrials, the Dow Transports have failed to break their early June highs. There are other divergences that drop out of our own methodology, but the basic picture is similar - small initial divergences which have a good chance of being resolved, but warrant attention nonetheless.

The second set of concerns is geopolitical. In recent weeks, there has been a marked deterioration in the prospects for global stability. Probably the only nexus that has enjoyed a reduction of tensions has been between India and Pakistan, largely owing to surprising and unilateral diplomatic efforts by the Indian Prime Minister that resulted in a sudden warming of relations between the two countries. Elsewhere, the shift has been decidedly toward escalation. This tendency is not confined to the Middle East. In Russia, Putin has announced a renewed effort to strengthen the country's military forces, including nuclear capabilities. Iran has announced nuclear intentions. The U.S. has quietly dropped a 10-year ban on the development of small strategic nuclear weapons. Hell, even Switzerland has announced substantial plans to "modernize" its military capabilities. This can't end well if the course doesn't change - if escalation and a hardening of positions is allowed to overwhelm diplomacy. All weapons are boomerangs. It's a law of physics.

With regard to the financial markets, you never want a situation that invites investor's imaginations to run wild. It's the imagination that encourages otherwise clear thinking investors to make astoundingly bad decisions on the belief that familiar economic or political conditions no longer apply. The loss of nuclear containment is one of those things that can get imaginations going, and it's not helpful when an Administration's actions have the effect of proliferating exactly the weapons it wishes to contain. The donut is peace and global stability. It would be wise to keep both eyes on the donut.

A final concern involves debt and interest rates. The major force shaping economic dynamics over the coming decade is likely to be an unwinding of the extreme leverage that individuals, businesses and the U.S. itself (via its record current account deficit) have accumulated. I've written at length about the impact that the current account deficit is likely to have in dampening sustained growth in domestic investment. Individual and corporate balance sheets are no healthier, of course, and this will make the U.S. economy vulnerable to future debt crises and shifts in the profile of interest rates.

As I've noted several times in recent years, the U.S. financial system has made a very large bet on the continuation of a steep yield curve (very low short-term interest rates and higher long-term rates). Many U.S. corporations have swapped their long-term (fixed interest rate) debt into short-term (floating interest rate), to the extent that an increase in short-term rates could substantially raise default risks. Similarly, a growing proportion of homeowners have refinanced their mortgages into adjustable rate structures that are also sensitive to higher short-term yields. Finally, profitability in the U.S. banking system is unusually dependent on a steep yield curve, with a widening net interest margin (the difference long-term rates they charge borrowers and the lower short-term rates they pay depositors) accounting for all of the strength in bank earnings in recent years.

Of course, if somebody owes short-term interest, somebody else must be earning it. Who owns all of this low interest rate paper if the companies issuing it are so vulnerable to default risk? That's the secret. The companies don't actually issue it. Instead, much of the worst credit risk in the U.S. financial system is actually swapped into instruments that end up being partially backed by the U.S. government.

See, a risk-averse investor might be somewhat reluctant to lend short-term money directly to, say, General Motors. To see how the U.S. government becomes a counterparty to this debt, grab a pen.

First, suppose that Citibank gets money from its depositors at a floating rate, and lends to mortgage holders at a fixed 6%. Now GM issues bonds yielding 7%, and enters a swap with Citibank, in which Citibank pays GM 6% fixed in return for floating + 1% (the U.S. swaps market for this kind of transaction is huge). Well, now GM is paying an actual interest rate of floating + 2% (pay 7% to bondholders, get 6% from Citibank, pay Citibank floating + 1%). Meanwhile, Citibank is earning a fixed 1% margin regardless of interest rate movements (pay depositors floating, get 6% from mortgages, pay 6% to GM, get floating + 1% from GM). Neat. And since Citibank is federally insured, Uncle Sam is now a counterparty that effectively shares the risk in the case that GM defaults. Similar transactions serve to swap risky corporate and mortgage borrowing into safe government agency paper issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Now make no mistake, I do strongly believe that bank deposits and government and agency debt are safely backed by the U.S. government and that this is a good commitment. The holders of stock in banks or mortgage companies like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac may not be so secure. For several years now, our stock selection approach has led us to avoid large commitments to financial company stocks.

The key point is that a lot of debtors have linked their borrowing to short-term interest rates. This is tolerated by the financial system because the debt has been swapped out through financial intermediaries like banks, so investors get to hold relatively safe instruments like bank deposits and Fannie Mae securities. Still, the mountain of debt in the U.S. financial system - tied to short-term interest rates - is ultimately and perhaps somewhat inadvertently backed by the U.S. government. This is likely to result in future money creation. Meanwhile, we aren't very willing to own much in the way of financial or mortgage company stocks, because these institutions may be vulnerable to credit problems even if their depositors and bondholders are not.

As with the other factors I've noted in this update, the debt situation does not necessarily resolve into short-term implications. Still, the situation is important enough to warrant constant monitoring. We're certainly willing to accept market risk when trend uniformity is favorable, but this is no seal of approval regarding the state of the financial markets, economy or geopolitical situation. The next decade will be very challenging, and there's no sense in being glib about it just because investors appear willing to accept greater risk over the near term.

On the basis of some of the minor divergences that have developed in recent sessions, we've taken a tiny position (less than 1% of total assets) in put options. But even that tiny position is sufficient to hedge nearly half of our exposure in the event of a deep decline. Assuming that market action remains clean, I expect that we'll sell these back out within a few weeks. "Clean" in this respect means market action that either clears or fails to extend the divergences we've seen lately. That's the most probable outcome, but we'll watch closely.

In the bond market, investors are not only allowing for the possibility of deflation, but have priced the expectation of falling inflation into the market. This leaves bond investors vulnerable. There's no question that the Fed will cut rates by at least 25 basis points. 50 is a possibility, but given the bit of strength in recent economic reports, it's an outside possibility. However, market determined interest rates are unlikely to follow, and I wouldn't be at all surprised if market interest rates were to move substantially higher, particularly on the short-term end (where the real risk seems to be).

If you look closely, you can see the bear market in the bull, and you can see the bull market in the bear. It is important to avoid the dualistic thinking that you have to take sides. The objective is not to choose a side and hope that it will win in the future, but to look closely in order to understand, and to act accordingly in the present.

So we're seeing a few divergences in the stock market that may be cleared in the coming weeks, but they're important enough to own a tiny hedge in response. In the bond market, we continue to avoid significant interest rate risk. Treasury inflation protected securities and precious metals shares are limited but important parts of our portfolio here.

![]()

Sunday June 15, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations and favorable trend uniformity. This combination holds us to a constructive position here. While our discipline can take tiny "contingent" option positions (generally a fraction of one percent of portfolio value) from time to time depending on some divergence or another that appears in market action, we will remain generally constructive until we observe a fresh shift to unfavorable trend uniformity.

One question that we've heard a lot lately - how far would the market have to decline in order to generate such a shift? Careful readers of these updates probably already recognize that this is not a simple question. As I've noted frequently, trend uniformity does not measure the extent or duration of a market movement, but rather its quality. For example, trend uniformity shifted to a decisively unfavorable condition on September 1, 2000 at S&P 1520.77 (the exact bull market peak was 1527.46). In contrast, a weaker shift that we saw following the July 2002 low was only reversed after a decline of about 10% from the August 2002 peak.

We don't attempt to forecast market direction or pick market tops. Still, if the market develops the kind of internal weakness that typically precedes major declines, trend uniformity can shift to a negative condition at or near the peak of a market advance. In historical data, the 1987 and 1990 bull market peaks were both accompanied by marked breakdowns in interest-sensitive sectors such as bonds and utility stocks, for example. But if there is no such internal weakness, trend uniformity allows much wider swings in the major indices (at present, perhaps 8-10% or more) before concluding that market conditions have shifted.

In short, we are taking a certain amount of risk here, based on very clear evidence on well-researched measures. There is simply no assurance that a market decline would result in a quick shift to a defensive position, but my expectation is that a negative turn in the market will be preceded by a variety of internal breakdowns in market action.

This isn't to suggest that there are no blemishes in the current market picture here, but rather that those blemishes are not the sort that have historically been decisive. Investor's Intelligence reports that only 16.3% of investment advisors are currently bearish - the lowest level in over 15 years. Yet as I've noted before, the implications of advisory sentiment are very dependent on surrounding context. We've reviewed these figures since they've been kept (early 1960's to the present), and find that when trend uniformity has been favorable, as it is now, bearish figures below 20%, 16% or other low cutoffs are simply not associated with negative near-term returns, on average. This is true even if we further restrict the data to periods of unfavorable seasonality and overvaluation. With regard to Friday's consumer sentiment figures, suffice it to repeat that consumer sentiment is actually a lagging indicator that can be predicted from past movements in indicators such as capacity utilization, inflation, and unemployment. The latest move was largely driven by the uptick in May unemployment. There are virtually no forecasting implications in this for the market or the economy.

Regardless of these blemishes, it is fairly rare historically for the stock market to enter sharp declines without some sort of internal deterioration in market action prior to (or quite early into) those declines, and it would be inconsistent with the evidence to expect the market to suddenly fall off of a cliff here. It's not impossible, but there's no basis for the expectation, or for investment positions that rely on that expectation.

One of the needless sources of difficulty for investors is the belief that investing requires the ability to forecast or even identify bull or bear markets in real time. The simple fact is that bull and bear markets don't exist in observable reality - only in hindsight. Think about this carefully - this is not a linguistic game but rather an invitation to focus on observable reality. At any given moment, the question of whether stocks are in a bull or a bear market is a subject of debate. Yet rather than looking strictly at observables, investors come to believe that they have to choose which side of the bull/bear debate they accept. Worse, once they accept one side or another, they detach from reality completely and begin to look at the market only from the position they've chosen.

For example, suppose that an investor decides that stocks are in a bull market here. Well, gee, the average bull market takes stocks well over 100% higher. And the average bull market within a secular bear period takes the market over 50% higher...

The problem with this sort of thinking is that it ignores observables. The fact is that stocks are already trading at about 18.4 times prior peak earnings, and except for the 1995-2000 bubble, even the 1929 and 1987 market peaks occurred at multiples less than 21 times peak earnings. So unless investors have learned nothing from the experience of the past three years (and I suppose we'll find out), it is reasonable to believe that stocks may have difficulty advancing by more than 10% or so from current levels. With trend uniformity still quite positive, we wouldn't take a defensive position on these views regarding valuations, but we certainly wouldn't join the chorus of analysts forecasting enormous gains from current levels.

The advice is simple. Seek first to understand. Drop your attachment to "positions" and look at all sides carefully. Don't attach yourself so closely to a label ("bull", "bear"), a side, or a position that you miss truth. It is a mistake to base your actions on concepts about reality that you can't even observe, on future scenarios you can't control, or on past conditions you can't recover. Take reality as your starting point. Not what you want reality to be, but what it is. So look closely.

By our reading, there are both favorable aspects and blemishes to current market conditions. For now, the favorable aspects dominate. But we are not attached to a positive or negative position - the evidence determines our actions as new information arrives. Frankly, I always wince at being called "bullish" or "bearish," because it assumes that new information could not arrive soon.

Of course, one of the worst ways to detach from reality is to use a theoretically unsound model that doesn't even have historical data on its side. I'm speaking of course of the Fed Model, which now hails stocks as 40% undervalued. Well, golly gee willickers.

Recall that the Fed Model compares the prospective earnings yield on the S&P 500 (expected operating earnings / S&P 500 index) with the 10-year Treasury bond yield. I won't review the extensive theoretical flaws again, but suffice it to say that the Fed Model has quite literally zero statistical correlation with subsequent market moves. Even the handful of apparently good historical calls are better captured by rules like "buy when stock yields are high and interest rates are plunging" and "sell when stock yields are low and interest rates are soaring." Other than those few calls, zip.

The Fed Model's record is particularly distressing when it gives "buy" signals during periods of low stock yields. In general, the only reliable inference from such signals is that bond prices are about to plunge. In short, when the Fed Model gives a screaming buy signal during a period of low stock yields, sell bonds.

![]()

Sunday June 8, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations but favorable trend uniformity, holding us to a constructive position. Last weeks' market action was particularly good in terms of uniformity - the NYSE recorded 1097 new highs and just 2 new lows. The only other instance in which the NYSE has recorded over 1000 new highs was the week of October 15, 1982. While I certainly don't view the market as similar to 1982 in any respect, it's clear historically that a large number of new highs is not a negative unless it is also accompanied by a large number of new lows - the bearish feature in that case being widespread internal divergence - we don't see that here.

Still, stocks remain overvalued, and neither strong market action nor the likelihood of good second-half economic growth will change that condition. Assuming that current, rich valuations will be sustained into the indefinite future (S&P 500 price/peak earnings currently 18.4, dividend yield 1.67%), stocks are priced to deliver long-term total returns of less than 8% annually. If the assumption of sustained overvaluation is removed and valuations move toward historical norms even a decade or two from now, the S&P 500 will deliver total returns in the neighborhood of 2-5% annually overall. Clearly, our willingness to take market risk here is based strictly on evidence of robust speculative merit, not long-term investment merit.

This does not mean that current market conditions are fragile or unreliable. To the contrary, historical market returns in the current Market Climate have been quite good on average, with somewhat below-average levels of volatility, regardless of valuation levels. We always allow for the possibility that the Market Climate will shift, which is why we never make forecasts even a few weeks into the future, but for now, we have no evidence by which to hold a substantially defensive investment position.

Last week, the Dow Industrials finally generated a Dow Theory confirmation by advancing past their November peak. While we don't actually use Dow Theory, we do respect it enough to keep an eye on divergences and confirmations under the theory. Against that favorable news, stocks are clearly overbought, and the percentage of bearish investment advisors has dropped to just 20% - lower than can be explained simply by appealing to the recent market advance. We wouldn't speculate on the possibility of a market pullback here, but we certainly wouldn't rule one out. In the current Market Climate, such pullbacks have historically represented reasonably good buying opportunities. Overall, we're constructively positioned, and inclined to use short-term weakness as an opportunity to purchase desirable investments.

There are two basic factors behind the market's strength here. First and foremost, investors have taken on a measurably greater willingness to accept market risk. Despite the fact that stocks are priced to deliver relatively low long-term returns, investors are willing to drive those prospective returns even lower, which results in higher prices over the near term. Remember, the higher the price investors pay for a given stream of future cash flows, the lower the long-term rate of return they accept on that investment (and vice versa). The second, much less important factor behind this rally is that investors are looking ahead to a certain amount of economic improvement in the second half; reasonably so from our perspective.

I say that this is a less important factor simply because stocks are a claim on a very long-term stream of future cash flows. Fluctuations in one or two years of those cash flows have very little impact on the discounted present value of the entire stream. Economic weakness doesn't hurt stock prices by reducing their long-term value, but by raising investor's short-term aversion to risk.

So the central fact of the recent rally is very simple: investors have become somewhat more willing to accept risk. We measure this willingness largely through market action in prices, yields and trading volume. When we begin to see divergences or breakdowns in market internals, it will be a signal that investors have become more more sensitive to risk, and we will quickly become more defensive. But for now, the willingness of investors to accept risk seems to be fairly robust.

Of course, you can always flip on the TV to hear analysts offering other reasons for this rally. You can usually identify which subject they flunked by the argument they make.

The econ flunkies argue that stocks are advancing because investors are "selling money market funds and buying stocks." The quickest way to cut through this argument is to ask "to whom?" and "from whom?" As I've noted before, if Mickey sells his money market fund to buy stocks, the money market fund has to sell commercial paper to Nicky, whose cash then goes to Mickey, who uses it to buy stocks from Ricky. In the end, the cash that Nicky used to hold is now held by Ricky, the commercial paper that Mickey used to hold (via the money market fund) is now held by Nicky, and the stock shares that Ricky used to hold are now held by Mickey.

Money never goes into or out of the market - merely through it. Every security issued must be held. Regardless of the trading that takes place, in aggregate, investors hold exactly the same amount of cash, commercial paper, and stock as they held before those trades. It's only the terms of trade that may change. To the extent that Mickey is eager to sell money market instruments and Nicky is not eager to buy them, Mickey has to give Nicky more money market instruments for a given amount of cash - that is, the price of money market instruments will decline, increasing short-term interest rates. To the extent that Mickey is eager to buy stocks and Ricky is not as eager to sell them, Ricky will sell fewer shares of stock for a given amount of cash - that is, the price of stocks will increase. Similar trades, but different price changes, would result if Ricky was the eager trader instead of Mickey (work through this as an exercise - it's worth the trouble). Still, in the end, any change in stock values comes down to changes in the eagerness to hold stocks, not to any aggregate change in the amount of stocks or cash held by investors.

Meanwhile, the math flunkies argue that the rally is due to the recent cut in dividend taxes. Look, the long-term total return on stocks breaks into two elements - income and capital gains. Long-term capital gains are already favorably taxed, so the only incremental change is the reduced tax rate on dividends (relative to what was already priced into stocks before the change), applied to the stream of dividends over the period to which the tax rate change applies.

Given a current dividend yield of 1.67% on the S&P 500 index, the 10-year dividend tax relief passed by Congress raises the long-term after-tax rate of return on stocks by just 4 basis points. In order to fully reflect this dividend tax change, stock prices would have to rise by only 2.5% (dropping the dividend yield by that same 4 basis points). Applying this change to the total market value of U.S. stocks, the entire impact on the capitalization of the U.S. stock market would be roughly $350 billion. This is an interesting figure, because it is none other than the present value of the dividend tax reductions just passed by Congress.

So we have an elegant and intuitive result: the justified increase in stock market value as a result of dividend tax reductions is equal to the present value of the tax reductions themselves. There's no such thing as free money.

If instead, the dividend tax relief is extended for 30 years, the long-term after-tax return on stocks would rise by about 9 basis points, justifying a stock market advance of about 6%. This larger increase in the capitalization of the U.S. stock market would mirror the larger cost, in present value, of extending this tax relief.

Arguably, whatever tax rate on dividends anticipated by the market beyond 30 years from today was probably already priced into stocks before the recent tax cuts anyway. Tax policy is simply too fluid and unstable to price long-term assets on static assumptions beyond that horizon. But only by unexpectedly and permanently reducing taxes on dividends would stock values be significantly affected. In the infinite-horizon case (assuming that no tax reduction was priced into the market prior to the change, and the entire tax reduction was suddenly priced into the market for the infinite future), the present value of the market would need to rise by about 20% in order to maintain a constant after-tax rate of return. Even this assumes that rich current valuations are actually sustainable over the long-term.

In short, recent tax changes may be part of investor's willingness to take greater stock market risk, but they have a negligible effect in raising the fundamental value of stocks. The entire exercise is worth less than 250 points on the Dow. Still, this negligible effect in terms of total market value still has a fairly heavy price tag in terms of tax revenues. There is a right way and a right time to adjust tax policy. This cut just sets the tax system up for a Clintonesque backlash. We certainly wouldn't price it into stocks for more than a decade or two, and doubt that the markets will either.

In bonds, the Market Climate continues to be characterized by extremely unfavorable valuations and favorable trend uniformity. Valuations, however, carry more weight in determining near-term fixed income returns than they do in stocks, so we are fairly defensive here. Alan Greenspan made some interesting comments last week, indicating the likelihood of markedly stronger economic growth in the second half - remarks strangely at odds with recent deflation talk. The whole deflation issue is increasingly looking like a pretense for further lowering of the federal funds rate rather than any deeply held conviction by members of the FOMC.

As I've noted before, a continued reduction in the demand of investors for "safe havens" is likely to result in a fairly abrupt increase in inflation rates. My opinion is that further easing in the federal funds rate is likely to be accompanied by increases in market-determined interest rates, and that the Fed could be forced to quickly follow suit. If this were to occur, we could see a much flatter yield curve a year from now, with much of the shift accomplished by higher short-term rates. I've already noted the difficulties a flattening yield curve could have on the banking and credit system. Suffice it to say that the greatest risk to the financial system here is not deflation, but rather a substantial flattening of the yield curve.

That said, we'll get plenty of evidence to confirm or refute these risks as the coming quarters develop, and beyond taking a relatively short-maturity stance based on the prevailing Market Climate for bonds, there's no need to take any investment positions on this basis just yet. For now, we're aligned with the prevailing Market Climates in stocks and bonds. We'll take our next steps as new information arrives.

![]()

Sunday June 1, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations but favorable trend uniformity. This holds us to a constructive position for now. While we certainly allow for a continuation of this advance, the market is quite overbought on a short-term basis, so we also have to allow for the possibility of a decline or flat period to clear that condition. Last week, a number of major averages broke through important technical resistance levels - for example, the S&P 500 finally broke above its August 2002 peak, and the Dow finally broke through its January 2003 peak. This creates a certain amount of short-term tension, because it can trigger short squeezes among the bears, while triggering profit-taking by the bulls. The certain result is high trading volume, which we've observed in recent sessions, but it leaves the near-term direction of the market in question. We won't get much information from whether the market advances or declines over the short-term here, but suffice it to say that should be prepared for greater than normal volatility in the coming week or two.

The most significant blemish in market action, in my view, is that the Dow Jones Industrial Average has yet to break above its November high, which would be required to confirm the break that the Transports have already made of the high set between the October and March lows (see recent updates for details). In my view, it's not nearly as important that the Dow break its August 2002 peak (which occurred before the deepest joint lows in October) as it is to break the November peak of 8931.68. I'm very aware that many investors view Dow Theory as outdated, if not antedeluvian. I'm still concerned about that nonconfirmation in the Industrials.

In the bond market, the Market Climate remains characterized by extremely unfavorable valuations and favorable trend uniformity. For bonds, however, valuations tend to have more impact on return/risk characteristics than they do for stocks, so we are fairly defensive here. I've noted before that any data that includes the month of April is likely to be quite awful, but not particularly informative. For example, the April Help Wanted Index came in at a dismal level of 35 - the worst level of the recession, and most probably the lowest level we'll see. Until help wanted and capacity utilization enjoy sharp jumps, the health of any economic expansion will be in question, and the risk of a shortened expansion (such as the brief 1980 experience) will remain. My own view of economic fundamentals is that any economic expansion we observe is unlikely to be vigorous or sustained. Thus far, the weakness in help wanted and capacity utilization are consistent with that outlook.

This does not, however, rule out several quarters of strong growth. While I don't suspect that the second quarter will be one of them, there is a growing probability that the second half of the year could be quite robust. Indeed, this is the first time that we actually have reasonable evidence for a "second-half recovery" - a constant theme that has become something of a running joke in recent years.

Near term, the May Chicago Purchasing Managers Index came in at 52.2, versus April's 47.6, suggesting that the national PMI may be stronger as well. Though the simple set of criteria I present in Going for the Gold includes the PMI as one indicator, our actual gold model is more complex, and even assuming a strong PMI, the Market Climate for precious metals remains in a very favorable condition.

We've received a number of questions regarding my opinion about the recent dividend tax cut (which was passed in watered-down form). I strongly believe that income should only be taxed once, with large exclusions from taxation at lower income levels, and rates as flat as possible at upper levels. The recent tax cut is curiously unsatisfying in these respects, correctly striking many observers as a reasonably good idea in concept, but poorly structured in practice, not particularly stimulative, and passed at the wrong time, under the wrong fiscal circumstances, and likely to exacerbate an already deep current account deficit. If you want a stimulus plan, you go where the problem is, which is saving and investment, and you create short-lived incentives such as an increased 2003 retirement contribution limit and investment tax credits to actually shift the time-profile of saving and investing. All the current plan does is reduce taxes on dividend recipients, leaving those recipients with some number of dollars, while increasing the government's debt by exactly the same number of dollars, so that in equilibrium the additional dollars held by the public must be used to purchase the additional debt that the federal government will now incur. As Milton Friedman has often argued, the burden of government is not measured by how much it taxes, but by how much it spends.

As for the impact on the stock market, stocks are priced to deliver poor long-term returns here, and the dividend tax relief provided in this plan does very little to change that. There is some distributional impact that makes income oriented stocks such as utilities modestly more attractive, but the analysts who argue that this dividend tax cut will create a permanently higher level of stock valuations are evidently not adept at discounting cash flows. Again, the overall impact is curiously unsatisfying.

As for the savings-investment identity, in response to several notes that have noted various objections, it is indeed an identity - you just have to work carefully through every source of cash. For example, suppose that a bank has $100 of reserves and lends them to Albert. Albert buys a machine from Bob, who deposits the proceeds into another bank, which holds onto $10 and lends $90 to Cindy, who buys a computer from Diane, who deposits the $90 in a bank... On the surface, one might think that the $100 of somebody's savings held at the bank resulted in a much larger quantity of investment. But looking closer, notice that the $100 of savings that was in the bank got invested in the machine that Albert bought from Bob. Bob then saved $100, $10 of which was held by the bank in reserves (and ultimately lent to the Federal government to offset its dissaving) and $90 of those savings were used by Cindy to buy the computer from Diane...

It's an accounting identity that GDP is exhausted by consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports (exports - imports): Y = C + I + G + X - M. Therefore, introducing taxes, it's also an accounting identity that (Y - C - T) + (T - G) + (M - X) = I. Private saving, plus government saving, plus foreign saving (via the current account deficit) equals investment. In practical terms, this means that in order to get more investment, we've either got to see an improvement in private saving (growth in after-tax income that exceeds the growth in consumption), an improvement in fiscal conditions through reduced crowding-out of investment by government spending, or a deterioration in the current account deficit (which is difficult when the current account is already in record negative territory). In the short-run, my bet is on output growth that outstrips growth in consumption, though both are likely to grow. But again, current economic fundamentals don't favor the prospects for powerful, sustained growth in investment.

Bottom line - we remain constructive in stocks and precious metals, and relatively defensive in bonds. The underlying fundamentals of the markets and the economy remain of concern, but there are clearly sufficient short-term pressures to affect how the economy and financial markets evolve over shorter periods. As usual, our investment stance is influenced by both valuations and market action. Valuations suggest that neither stocks nor bonds are priced to deliver attractive long-term returns. For now, however, market action remains decidedly favorable, possible short-term volatility notwithstanding.

![]()

Monday May 26, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations but favorable trend uniformity, holding us to a constructive position - fully invested in a broadly diversified portfolio of stocks, with about one-quarter of that exposure hedged against the impact of market fluctuations.

The market risk that we have taken here is inherent in the stocks we have selected. Importantly, these stocks are chosen because we believe that they display additional merits; specifically, each of these stocks has entered the portfolio based on some combination of favorable valuation and market action. Since the inception of the Strategic Growth Fund in 2000, the performance of our favored stocks has strongly exceeded that of the major indices.

Of course, past performance does not ensure future results, and certainly not consistently positive short-term results. As I've noted previously, the low-volume market environment prior to military action in Iraq made it very difficult to gain traction from characteristics that the market usually rewards over longer periods of time, including the measures we emphasize. The result was several months of dull performance. In recent weeks, trading volume has picked up considerably, which has been a favorable development. Investors have also been willing to accept greater market risk overall, which is helpful. Certainly, we can expect a largely unhedged position to experience greater volatility than a fully hedged position would. As always, we take risks that we expect to be compensated, on average. Our willingness to take market risk here is no exception.

Will Rogers once said "It ain't what people don't know that hurts them. It's what they do know that just ain't so." We are very aware of the bearish arguments concerning overvaluation, debt burdens, current account deficits, seasonality, geopolitical risks, and other factors. Indeed, the latest issue of Research & Insight reviews these in detail. However, the fact is that these indicators are not closely correlated with near-term market returns.

Consider advisory sentiment. Last week, the percentage of bearish investment advisors reported by Investor's Intelligence dropped to just 20.9%. We carefully analyze these figures, because they do carry information. But the key is understanding how to extract that information. As I've frequently noted, just as the "news" isn't in the earnings number but in the surprise, information is often contained in the divergence between a particular piece of data and what would be expected.

It is one thing for advisory bearishness to be low during a period of negative market action. Low bearishness in an environment of weak market returns is a real negative because it is out-of-context. It suggests that investors have been caught by some "hook" that is enticing them to ignore market behavior. In contrast, low bearishness following strong rallies is not unusual or particularly informative - if you look at most bull market periods, you will see very sharp declines in bearishness and spikes in bullishness that are not followed at all by subsequent market reversals. So no data point can be taken at its face value without considering the context in which that data resides.

Reviewing the history of the Investor's Intelligence figures since the 1960's, even bearish percentages of 25% and lower have been associated with subsequent market returns of nearly 15% annualized, on average, during periods of favorable trend uniformity (which we currently observe). Market returns remain quite good even if the data set is further restricted to periods of overvaluation and unfavorable seasonal conditions (May-October). In short, context matters.

Similarly, the preponderance of new highs versus new lows might be seen as an indication of an overextended market. Over the past three weeks, new highs have outpaced new lows by a factor of at least 25-to-1. Yet in fact, this sort of preponderance is typically associated with the relatively early phase of bull markets, not bear markets. That's just an observation - I don't really think in terms of bull and bear markets, and I certainly don't mean that as a forecast. To use our own terminology, a preponderance of new highs is a kind of uniformity across a wide range of stocks. The time to worry is when new lows start increasing despite new highs in the major indices. Such internal breakdowns are informative exactly because they are out-of-context. Reviewing history, the most notable instance in which a lopsided high/low ratio was followed by a sharp decline (about 12%) was in mid-1975; a decline that was quickly recovered and followed by substantially higher prices. That's not any assurance that stocks will rally in the present case, but again, the average performance of the market has been quite good when the market has enjoyed strong leadership from new highs.

Again, these comments should not be interpreted as forecasts. Given the relatively strong rally we've seen in recent months, there is nothing that prevents the market from experiencing a deeper correction than we saw last week. But there is not sufficient evidence on which we can base an expectation of negative returns.

Historically, a buy-on-dips approach has generally been rewarded in the present Market Climate. Given that the average return has also been favorable in this Climate, it has not generally been rewarding to wait for such dips, and certainly not to wait until they carry all the way to oversold conditions. In my view, even last Monday's decline was a reasonable buying opportunity.

There is a world of difference between responding to market movements because of the opportunity they offer, and reacting to market movements because of the emotion they create. One never knows whether a specific purchase or sale will be rewarding, but it is extremely important for investors to make a habit of buying favored securities on short-term weakness and selling lower-ranked holdings on short-term strength. This can also be done on a relative basis. For instance, there is nothing wrong with selling a stock on a 5% decline if the more attractive one being purchased is down 10%. Unfortunately, many investors make a habit of buying stocks (or funds) only after they have been convinced by a relentless series of advances, and of selling during flat periods or outright declines - not for analytical reasons, but simply out of fear and impatience. This sort of habit is suicide.

Investment actions should be driven by the merits of the security, not by the position you already have (unless your position invites the risk of unacceptable losses, in which case you should lighten up regardless of market action). If you own a security that is declining in price, ask yourself what you would be doing if you didn't own it. If you would be inclined to buy it on the decline, you should re-think your impulse to sell. Similarly, if you don't own a security that is soaring in price, ask yourself what you would be doing if you did own it. If you would be inclined to sell it into the rally, you should re-think your impulse to buy. There are a few cases when a particularly attractive security should be bought even on strength, or a particularly unattractive security should be sold even on weakness. But as a general rule, the idea is to buy low and sell high. This should be obvious, but having observed the actions of countless investors over the years, I can assure you that it is not.

In the bond market, the Market Climate is characterized by extremely unfavorable valuations, but tenuously favorable trend uniformity. Since bonds are not as subject to "bubbles" as stocks are, favorable trend uniformity alone is not sufficient to warrant taking substantial bond market risks. Still, to the extent that the bond market can experience bubble-like features, the U.S. bond market is currently doing exactly that.

Like the stock-market bubble three years ago, the same force is behind the current action in bonds: Alan Greenspan. The word "deflation" is to the bond market what the phrase "structural productivity growth" is to stocks. In both cases, Greenspan has been the head cheerleader (no need to linger on that visual).

Over the past year, we've noted that the most probable outcome for prices is not likely to be deflation but a divergence in inflation rates for manufactured goods versus services. Excess global manufacturing capacity, combined with a massive trade deficit, does place downward pressure on the prices of imports and manufactured goods (though less so in the face of a weak dollar). Still, the labor market remains relatively tight compared with past recessions. Since rents generally accrue to the scarce factor, the main beneficiary of the economic growth that does occur will not be capital (or profit margins) but labor. So wage inflation and services prices are likely to experience continued upward pressure. The overall result is likely to be a relatively low but persistently positive level of overall inflation when measured over any reasonably extended period of time.

Further reasons to expect positive inflation (based on the exploding supply of government liabilities combined with a likely ebbing in the demand for safe-havens) can be found in the latest issue of Research and Insight.

The recent surge in the value of the euro versus the U.S. dollar has been a largely predictable move toward fair value (see Valuing Foreign Currencies. As I've frequently noted, movements in currency values are driven primarily by real interest differentials between countries. The plunge in U.S. Treasury yields, combined with still positive inflation pressures, represents clear downward pressure on real U.S. rates, and is one of the key factors behind the weak dollar and recent strength in precious metals. Both markets are vulnerable to corrections, of course, but the pressure on U.S. real interest rates remains in force.

To the extent that movements in the U.S. dollar reflect real interest rate movements, we can consider dollar weakness to be a valuation move, not evidence of disinvestment by foreign investors. We would be concerned if the decline in the dollar was to substantially exceed what is warranted by real interest rates. In that case, dollar weakness could indicate a reduction in the willingness of foreign savers to purchase U.S. securities. This foreign investment finances a substantial portion of U.S. domestic investment, so a pullback in this financing would be a real negative. For now, we don't observe this. In the absence of a flattening yield curve, widening credit spreads, unfavorable trend uniformity and other evidence, recent dollar weakness does not reliably indicate oncoming economic weakness.

As always, context matters. With the exception of data that includes April (which will be predictably weak), we don't have strong evidence to expect an oncoming downturn in the economy. Fundamentals such as debt burdens and overcapacity remain relatively unfavorable, but those fundamentals only exert their influence over the long-term. In the meantime, market action provides the most reliable information about how the economy will evolve over shorter horizons.

![]()

Sunday May 18, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations but favorable trend uniformity, holding us to a constructive position here. Our willingness to take the market risk inherent in our favored stocks should not be taken as a forecast of future market conditions, but rather an identification of prevailing ones. Historically, the Market Climate we currently identify has been associated with attractive market returns at somewhat below-average levels of volatility while it has been in effect.

Our refusal to predict market direction over the coming months or quarters is due to the fact that we base our investment stance on prevailing evidence. To predict market conditions into the future needlessly rules out the possibility that new evidence will arrive. Do not make the mistake, however, of interpreting this to mean that current evidence is weak or highly subject to change. It isn't. In general, the Market Climate shifts less than twice a year, and we do not take shifts lightly. It's just that there's no need to forecast, make claims about whether stocks are in a bull or bear market, or predict how long favorable conditions will persist.

It is a great source of misery to approach life with the wish that reality would be something other than it is. If you're at the mall, in front of the directory, and the little red arrow says "You are here," then the quickest way to your goal is to accept reality and go from there, rather than making yourself miserable by wishing you were in front of Nordstrom instead of Sears. Same with the market. We identify where we are, based on measures that are theoretically sound and historically well-tested. When those measures shift, so does our position. The worst thing you can do is to deny reality by neither accepting it, responding to it, or taking actions to learn from it. From some of the notes I've received, a lot of heavily short bears seem to be taking this risk.

I'm not saying that the bearish case is wrong. I just don't have the evidence, on balance, to join that position here. Based on still-high valuations, my opinion remains that stocks are in what will be seen in hindsight as a protracted or "secular" bear, in which the market moves from extreme overvaluation to durable undervaluation through a series of bull and bear moves, with each bear market achieving successively lower and more attractive levels of valuation. So current valuations are useful in framing the long-term prospects for the market. But they don't say much about the path that the market will take to get there. For that, trend uniformity is much more instructive. At present, we've got favorable evidence on that front. As I note in the latest issue of Research & Insight, the overall economic picture does have important blemishes, but historically, even overvaluation, bullish advisory sentiment, and negative seasonality have not been capable - individually or in combination - to generate poor market returns, on average, during periods of favorable trend uniformity. In short, we have no evidence to take anything other than a constructive position here. We're not aggressively positioned, but we're certainly in a position that we would expect to participate in broad market movements.

Finally, keep in mind that the market risk that we've taken is inherent in the broadly diversified portfolio of stocks that we own, which are selected because we believe they display further individual merits such as favorable valuation and market action.

The recent rally has created enough confidence among the bulls to drag the "Fed model" out of its festering compost pile. This always happens near troughs in the 10-year Treasury bond yield. Statistically, the Fed model is useless as a stock market indicator, having an overall correlation of almost exactly zero with subsequent market movements, even including a few apparently good calls. Those few good calls are better captured by a simple rule: buy when stock yields are high and bond yields are plunging, sell when stock yields are low and bond yields are soaring. As I've noted before, while the Fed model is dismal as a stock market indicator, it is ironically a fairly useful bond market indicator. In general, when the Fed model says that stocks are undervalued (based on a S&P 500 projected earnings yield above the 10-year Treasury yield), it has historically been a fairly good signal that 10-year Treasury yields are about to shoot higher.

A related argument is that P/E ratios should be higher because inflation is lower now than in the past. There are two difficulties with this. First, "the past" in this context is post-1965 data. From a longer term perspective, there are many periods when interest rates and inflation were much lower and more stable than at present, while P/E ratios were also lower. Yet even if a sustainably higher P/E ratio was justified, a high P/E ratio is not an argument that future stock returns will be high, but rather, that durably low stock returns are OK. Historically, real GDP growth has run at about 2.7% annually (a sustained growth rate even half a percent higher than that would be an enormous economic achievement). Historically, S&P 500 earnings growth, peak-to-peak, has grown no faster than nominal GDP. So to the extent that future inflation is persistently lower, so too will be nominal earnings growth. So suppose that the sustainable future P/E ratio on peak earnings is 20 (the same as at the 1929 and 1987 peaks) and that long-term inflation will be only 2% annually. In that case, we're looking at peak-to-peak earnings growth of about 2.7% + 2% = 4.7% annually. Holding the P/E ratio constant at 20, prices would grow at the same rate as earnings, so 4.7%. Add in the 1.3% dividend yield you'd get at a sustained P/E of 20, and stocks would be priced to deliver a long-term total return of 6% from those levels. So again, even if low long-term inflation was to produce sustainably high P/E ratios, the result would not be high long-term returns on stocks, but sustainably low long-term returns.

In any case, we don't buy the low long-term inflation argument (see the latest issue of Research & Insight for details). From a valuation standpoint, stocks are priced to deliver fairly poor long-term returns. Our valuation work doesn't align well with analysts who assert that stocks are cheap here. Frankly, I take a certain amount of comfort that it aligns with analysts we respect, including Warren Buffett and Bill Gross - guys who understand how to discount a stream of cash flows. Still, the simple fact is that there is room for valuations to move higher, and when trend uniformity is favorable, that has historically been the tendency. So our argument is more about the path that the market is likely to take rather than the destination.

A few comments about market action from the standpoint of others that we respect. While our market posture won't always agree with other analysts, the two I'll mention here - Jim Stack and Richard Russell - do careful, original work that is worth taking into account regardless of whether their conclusions match our own at any particular point in time.

Jim Stack of Investech notes that the Coppock Guide has recently turned higher (a relatively rare signal based on lagged market returns). While there have been a few false signals historically, an upturn after a move toward or below zero has always accompanied new bull markets. Stack also notes correctly that the recent downturn in the ISM Purchasing Managers Index and consumer confidence were not confirmed by a downturn in the market (as they typically are prior to recessions). As we frequently note, information is contained in the divergence between what the market does and what it would be expected to do in the context of other evidence. Investech's "negative leadership composite" (which measures a dearth of new lows which generally confirms important reversals in the major trend) also turned favorable last week.

Meanwhile, Dow Theory is in an interesting position here. Though we don't use Dow Theory directly (preferring our own theoretically derived and tested Market Climate approach), this is no great criticism. In fact, regardless of how much statistical or theoretical firepower we could muster, it would be difficult to find a more useful approach based on two market indices than Dow Theory itself.

Dow Theory is often misinterpreted as a purely technical approach that gives buy signals when both the Dow Industrials and Transports hit new highs, and sell signals when they both hit new lows. This is simply false, and vastly understates the subtlety and richness of the theory, as well as its strong emphasis on value. As Charles Dow wrote a century ago, "The best way of reading the market is to read from the standpoint of values. The market is not like a balloon plunging hither and thither in the wind. To know values is to comprehend the meaning of the movements of the market. Stocks fluctuate together, but prices are controlled by values in the long run."

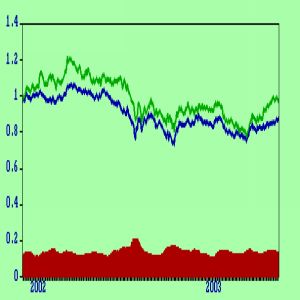

While it would be impossible to do a meaningful exposition of Dow Theory here, I think it's worthwhile to look at recent market action through that lens, starting with a great bit written over 40 years ago by Richard Russell, and accompanied by a chart of recent market action (appropriately scaled) featuring the Dow Industrials (blue), Transports (green) and NYSE trading volume (red).

"The market at the bottom becomes immune to the most shocking news, and the last decline usually is accompanied by very

low volume... The first decline following the rally should be scrutinized. If one or both Averages then hold above the previous lows and

volume diminishes as those lows are approached, it will be the most bullish indication since the bear market

commenced. Purchases here would be warranted on the assumption that the tide may have

turned up. In some few cases, buy-spots do prove false. Here the Dow Theorist finds himself holding securities which he purchased

at the buy-spot, and after this both Averages violate their previous lows. The only thing to do in such cases is to jettison

the recent acquisitions and pay the cost of "insurance" against a possible severe reaction...The actual bull signal is given when

on the second advance (preferably on increasing volume), both Averages top the highs of the first advance. This is the turn

in the tide, and those who have not made purchases already should buy on the next decline that is accompanied by decreasing

volume."

- Richard Russell, The Dow Theory Today, 1958-1960

Based on the last set of joint new lows in the Dow Industrials and the Dow Transports, the October trough marks the low point of the bear market to-date from the standpoint of Dow Theory. This low occurred on smaller volume than the July decline. The averages rallied off of that low, and then declined into early March on even lighter volume. At that point, the Transports hit new lows, but the Industrials did not confirm. This is the point at which a Dow Theorist might have been moved to establish a trading position, either using a stop-loss, or using call options. Though we don't use Dow Theory in our own analysis, more complex but related considerations led us to purchase call options at that point, as a "contingent asset" which, as it turned out, allowed us to take off a substantial portion of our hedges during the subsequent advance.

Soon after, Richard Russell (who still publishes the excellent Dow Theory Letters) saw enough speculative pressure in the market to advise trading purchases on March 25th, as his "Primary Trend Index" turned bullish. This occurred coincident with a Lowrys 90% up-day, a turn in the Lowry's buying/selling pressure figures, a plunge in short selling by commercials, and the reluctance of the Dow Industrials to confirm the new low in the Transports. Importantly, however, the emphasis of Dow Theory on value makes it clear that any "bull market" that might emerge from this action should be taken with long-term skepticism, as secular bear markets ultimately end with stocks trading at great values, and the current market does not qualify in that respect.

From the March lows, the subsequent rally took the averages higher for several weeks, followed by a pullback and rallies above the March highs in both indices (the Industrials doing so a few weeks later than the Transports). That was a good sign, but it is not sufficient to define a bull market from the standpoint of Dow Theory. As Russell wrote, "The actual bull signal is given when on the second advance (preferably on increasing volume), both Averages top the highs of the first advance. This is the turn in the tide, and those who have not made purchases already should buy on the next decline that is accompanied by decreasing volume." This takes us back to the "first advance" highs registered on the rally that followed the October low. The Transports have broken their January high of 2421.71, but to confirm, the Dow still needs to break 8931.68, a level it hit in November. The longer the Dow fails to do this, the more important the non-confirmation. And as with our own approach, an improvement in market action on a technical basis would not make stocks a great value, so stocks at that point would still be displaying only speculative merit, not investment merit.

All of this comes together in the following picture. Following the October lows, the market retreated to March lows on lower volume, and failed to produce a downside confirmation in the Dow Industrials (not to mention a variety of other indices). At that point, the market showed an initial flash of speculative merit. Since then, a wide variety of important technical measures (i.e. based on broad market action) have turned favorable. While valuations are too high to create a satisfactory investment environment where stocks could be expected to deliver strong long-term returns, we are seeing market action that is more characteristic of sustainable advances than of ongoing bear markets. Still, from our own perspective, we are reluctant to define stocks as being in a bull or bear market, because neither can be identified in real time (only in hindsight), and because both terms have a forecasting implication that we see as counterproductive. For now, our own approach is constructively positioned. From the standpoint of Dow Theory, a rally above Dow 8931.68 would add an additional confirmation to reinforce the early speculative signals that Dow Theory has already given, but it would not make stocks a better value.

Stocks have historically generated attractive returns, on average, in the Market Climate we currently identify. That doesn't mean that stocks are undervalued. It doesn't mean we are forecasting a powerful continuation, or ruling out the possibility that the market will decline. It does mean that for now, the expected return/risk characteristics of the market are favorable, and we have no evidence to hold anything but a constructive position. Given our views about market valuation, we don't see stocks as having achieved a durable low from which strong long-term returns will emerge. That also means that we expect to be fully hedged at some point in the future when market action again begins to display internal breakdowns and divergences.

For now, however, we don't see these negatives, and we have to allow for the possibility that the market could do what it has regularly done even as part of ongoing bear markets - recover somewhere between 1/3 and 2/3 of prior bear market losses before failing again. A 1/3 retracement of the peak-to-trough decline in the S&P 500 would still carry the market about 10% higher. A 1/2 retracement would carry the market nearly 25% higher. We view a 2/3 retracement as implausible on a valuation basis, but can't rule it out on other grounds. None of these are forecasts, but they are varying levels of possibility. Until the Market Climate shifts back to a negative position, they are also possibilities that appear more likely than their downside counterparts.

![]()

Sunday May 11, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

Just a note: The latest issue of Hussman Investment Research and Insight will be posted to the Research & Insight page of the website by about Tuesday of this week.

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations but favorable trend uniformity. This holds us to a constructive but not aggressive position in stocks. At present, we remain fully invested in favored stocks, with just under 30% of the portfolio hedged against the impact of market fluctuations. The market remains strongly overbought here, so we have to allow for the possibility of a near-term selloff (as usual, not a forecast). In that event, relatively low trading volume would be a favorable indication. The bear market rallies we've seen in the past three years have generally become dull on advances and active on declines. Market breadth has also been quick to deteriorate, and new lows quick to expand. The advance we've seen thus far is showing much different characteristics. It will be encouraging if volume generally continues to be strong on upmoves and rather dull on declines.

I've clearly hit a nerve with the bears, and I can understand the frustration of investors who have been short during this advance. I can't speak for them here, and the dollar value of our shorts wouldn't exceed our long holdings even if we were among them. So my only comment is this. To an investor who follows a carefully researched, theoretically sound, and historically tested approach, short term setbacks are an opportunity to exercise patience, stick to your plan, and continue your research. Look, our discipline has moved us to the constructive side. We need to adhere to that discipline, so why get all upset over a fact? To the bears who disagree, all I can encourage you to do is stick to your own approach and be absolutely certain to entertain the possibility that you're wrong, by doing hard research that encompasses an extensive span of history. We've certainly done the same.

I'll have more extended comments about market conditions in the latest research letter.

In the bond market, the Market Climate is characterized by unfavorable valuations and tenuously favorable trend uniformity. When bond yields are very depressed, unfavorable valuation carries more weight than it does in the stock market. Long maturities in anything other than inflation protected Treasuries just aren't worthy of the potential risk. Needless to say, we view the current discussion about deflation risks to be sorely misplaced, and an opportunity for holders of long-term bonds to shift down their maturity profile.

In our view, credit spreads in corporate debt are also becoming compressed. Given modest but positive prospects for economic growth in the near term, we don't observe much pressure for corporate spreads to widen, but the rapid narrowing is probably behind us, and with it, the unusually strong returns on low-grade debt.

With regard to foreign currencies, last week's action brought the euro in line with what we calculate as fair value (see Valuing Foreign Currencies. The yen still appears cheap in relation to the U.S. dollar. Still, with the U.S. current account extremely negative, and every prospect for continued federal deficits, I suspect that the dollar will remain under pressure (though a brief, sharp rally would clear the deeply oversold condition that developed last week).

In gold, we've seen some good strength, not surprising given that all four conditions noted in Going for the Gold are currently favorable. I don't suspect that the ISM Purchasing Managers Index will remain below 50 for long, but unless an expansion is accompanied by a fairly sharp spike in interest rates that raises real U.S. interest rates substantially, the Climate for precious metals shares is likely to remain favorable for at least a few more months.

![]()

Sunday May 4, 2003 : Weekly Market Comment

Copyright 2003, John P. Hussman, Ph.D., All rights reserved and actively enforced.

Press "Reload" on your browser to access the latest update file

The Market Climate for stocks remains characterized by unfavorable valuations but favorable trend uniformity, placing us solidly in a constructive position. At present, the Strategic Growth Fund is fully invested in a diversified portfolio of favored stocks, with about 28% of that value hedged against the impact of market fluctuations. The extent of that hedge will vary depending on a wide range of technical and economic factors, but given current valuations, I don't anticipate being less than about 20% hedged, nor more than about 40% hedged so long as trend uniformity remains favorable.

Importantly, the fact that we have a modest hedge in place means that we expect less volatility than a fully unhedged position might experience, but it does not imply that the Fund will necessarily lag market advances. Recall that the Fund's performance over the past few years has been achieved while being fully hedged against the impact of market fluctuations, the dollar value of our shorts never materially exceeds our long holdings. Nearly all of the Fund's gains since inception can be traced to the fact that our favored stocks have strongly outperformed the market over time. Keep in mind that the Fund's overall performance is driven by stock selection as well as market exposure.

As always, our willingness to take a constructive stance here should not be interpreted as a forecast or a "bullish call." Nor should it be considered a change in strategy. We continue to faithfully execute the approach articulated in our Prospectus. This is quite emphatically a growth strategy, with added emphasis on defending capital in unfavorable market conditions (defined by the combination of valuation and trend uniformity). While the short term consequences of our actions will vary based on factors we can't control, we relentlessly follow the same discipline, and the same set of daily actions. We look for opportunities to buy higher ranked candidates on short-term weakness, replace lower ranked holdings on short-term strength, and align our overall exposure to market risk with the prevailing Market Climate.

Our presently constructive position is based on prevailing conditions, and our investment position will shift when we identify a shift in those conditions. I have no idea when that will occur. On average, stocks perform well when trend uniformity is favorable (though best when valuations are favorable as well). When trend uniformity is favorable, I generally expect surprises in earnings, the market, and the economy to be on the favorable side. But since I have no idea when trend uniformity will shift, it is impossible to form any sort of meaningful forecast even a few weeks or months into the future.